Julian Gomez-Cambronero, biochemistry and molecular biology professor at the Boonshoft School of Medicine, explores the molecular biology of tumor progression and metastasis in breast cancer.

Researchers at the Wright State University Boonshoft School of Medicine are aggressively attacking breast cancer by exploring the molecular biology of tumor progression and metastasis. They are working to identify the molecules and signaling pathways that confer cancer cell aggressiveness to develop effective, targeted therapeutic drugs.

Julian Gomez-Cambronero, Ph.D., professor of biochemistry and molecular biology and Brage Golding Distinguished Professor of Research in the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, is working with members of his laboratory to find the molecular mechanisms that lead to breast cancer cell growth and invasiveness.

“Breast cancer ranks second as a cause of cancer-related death in the United States in women. It is estimated that one in eight women in America will develop invasive breast cancer in their lifetime,” Gomez-Cambronero said. “More than 40,000 women in the United States will die from breast cancer in 2017.”

The five-year survival rate of breast cancer dramatically decreases from 100 percent in Stage 1 non-metastatic disease to 22 percent in Stage IV advanced metastatic disease.

“The high mortality rate found in breast cancer patients stems from its high tendency to develop into an aggressive and metastatic state, especially to the nearby lungs, brain and bone,” Gomez-Cambronero said. “This is a terrible disease, and we hope to conquer it.”

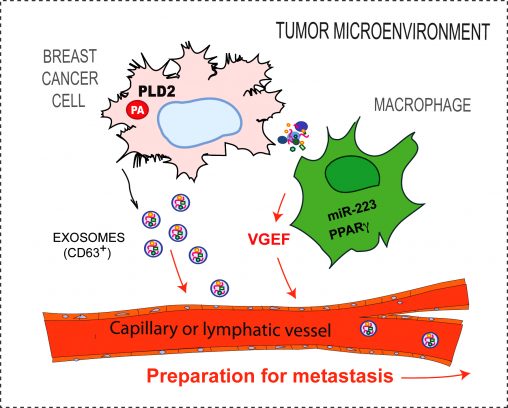

His lab is researching the role of small cell-made vesicles, called exosomes, that are released by a cancer cell as a means to communicate with the microenvironment to make possible the growth of the tumor. Those particles also travel through blood to arrive at places in the body far from the original tumor and prepare optimal niches for the arrival of metastatic tumor cells.

“Clearly, those exosomes represent a clear and present danger for the health of the patient,” he said. “We develop methods to counteract their actions with inhibitors that will potentially compromise metastasis seeding.”

Julian Gomez-Cambronero, Ph.D., is working with members of his laboratory to find the molecular mechanisms that lead to breast cancer cell growth and invasiveness. This diagram shows a macrophage in the tumor microenvironment.

They also are exploring the role of certain enzymes that control the stability of messenger RNA molecules (mRNA) that transfer DNA information into the making of proteins. One of these enzymes, called PARN deadenylase, expresses a very low activity in the breast cancer cells studied in the lab, which causes many of the mRNAs to accumulate in the cell interior and provide instructions for the making of oncogenic proteins that promote breast cancer cell growth and invasiveness. They have observed ways to reverse this process and impede cell growth in tissue cultures. Their research has been published in two journals, Advances in Biological Regulation and Biology Open.

In addition, Gomez-Cambronero and his laboratory are studying the tumor microenvironment, the tissue surrounding and intricately mixed with the tumor’s cells. This microenvironment is comprised of cells of diverse origin, including the immune system, that have been tricked and form chemical signals derived from the malignant cells into helping the tumor grow. Prime examples of these immune cells are certain types of macrophages. Their research has been published in PLOS One.

“We are looking at the implication of macrophages in the tumor microenvironment and are trying to understand why macrophages are polarized from being anti-tumor to pro-tumor,” Gomez-Cambronero said. “We have found a potential way to stop the process.”

In another research project, Gomez-Cambronero and his research team found how specific micro-RNAs (miRs) regulate cell invasiveness and aggressiveness of metastatic breast cancer cell lines as they attempt to overcome nutrient starvation and survive in harsh conditions where normal, healthy cells would die. Their research was published in Molecular and Cellular Biology, Molecular Oncology and Journal of Biological Chemistry.

The Wright State University Boonshoft School of Medicine is a community-based medical school affiliated with seven major teaching hospitals in the Dayton area. The medical school educates the next generation of physicians by providing medical education for more than 459 medical students and 458 residents and fellows in 13 specialty areas and 10 subspecialties. Its research enterprise encompasses centers in the basic sciences, epidemiology, public health and community outreach programs. More than 1,500 of the medical school’s 3,328 alumni remain in medical practice in Ohio.

Wright State became an independent institution in 1967 and has grown into an innovative leader in the Dayton region and beyond, capturing the spirit of the university’s namesakes, Wilbur and Orville Wright, who invented the world’s first successful airplane from their Dayton bicycle shop. It celebrates its 50th anniversary as an independent public university in 2017.

Wright State became an independent institution in 1967 and has grown into an innovative leader in the Dayton region and beyond, capturing the spirit of the university’s namesakes, Wilbur and Orville Wright, who invented the world’s first successful airplane from their Dayton bicycle shop. It celebrates its 50th anniversary as an independent public university in 2017.

Wright State alum Lindsay Aitchison fulfills childhood space-agency dream

Wright State alum Lindsay Aitchison fulfills childhood space-agency dream  Wright State business professor, alumnus honored by regional technology organizations

Wright State business professor, alumnus honored by regional technology organizations  Wright State University Foundation awards 11 Students First Fund projects

Wright State University Foundation awards 11 Students First Fund projects  Gov. DeWine reappoints Board Treasurer Beth Ferris and names student Ella Vaught to Wright State Board of Trustees

Gov. DeWine reappoints Board Treasurer Beth Ferris and names student Ella Vaught to Wright State Board of Trustees  Joe Gruenberg’s 40-Year support for Wright State celebrated with Honorary Alumnus Award

Joe Gruenberg’s 40-Year support for Wright State celebrated with Honorary Alumnus Award