While in New Orleans, Wright State students visited William Frantz Public School, where in 1960 Ruby Bridges became the first African American child to desegregate the school.

“This pilgrimage was an incredible experience and journey that is hard to put into words that can adequately explain the education and emotional journey it took students on. Seeing the landmarks and memorials to the struggle that is still very much alive even now in 2019 made everything I had learned up until that point real and visceral. Observing the strength and resilience of a people kidnapped and forced to assimilate was sobering and eye opening, shedding light on topics often covered up or ignored by the mainstream historical narrative. The hope that many were able to carry in the most desolate and unforgiving circumstances is more than I think I could have done.

“The importance of this experience to my personal growth and educational journey cannot be measured quantitatively; rather it is constantly informing my educational goals and practical application of the tenants of the civil rights movement to my daily life and future career.” —Chloe Peterson, social work.

That blog post is one of the many reflections of Wright State University students who spent their spring break on a pilgrimage to historical sites associated with the civil rights movement. The itinerary included landmarks in Montgomery, Alabama; Jackson, Mississippi; and New Orleans.

The Civil Rights Pilgrimage has become an annual alternative to spring break at Wright State. A third of the students participated as part of a spring semester class taught by Tracy D. Snipe, professor of political science; however, the trip was open to any student.

“I wanted to go on this trip because we’re busy and go every day, and don’t think about our history,” said Trenton Miller, a senior marketing major. “It’s a good way to remember where we come from, our roots and the untold history.”

Snipe personally created the pilgrimage and has led the group for seven years. Nycia Lattimore, assistant director of the Bolinga Cultural Resources Center, helps to administer the program and guide the group. Private funding from philanthropic groups and individuals helps make the trip possible.

While making preparations for the next pilgrimage, Snipe will also teach a class, French Politics and Society during summer A term. Parallel themes will also include an emphasis on civil society and civil disobedience.

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice was an emotional stop for Wright State students on the Civil Rights Pilgrimage.

Others outside of Wright State see the value of this program. “The youth being exposed to the past is more of a learning experience,” said Delbert DuBois, a community activist and environmental civil rights speaker in South Carolina, who has joined parts of Wright State’s pilgrimages for three years. He noted the importance of Snipe’s overall vision for the program and teaching the class because it connects the pilgrimage and the classroom experience, more so than readings or media coverage.

“I work with other major universities in different capacities, but the experiences I’ve seen from this Wright State program is the ultimate learning experience,” DuBois added. “Exposure is 90 percent of learning.”

During the pilgrimage, students would break into groups to discuss their perceptions and gut reactions. After returning to campus, students gathered together and shared the following reflections about how this experience has left lasting impressions.

“What was most moving was seeing how colloquial things were. I think we view African American history in an academic way. It was beautiful to see how these messages of freedom and victory translate; the message has to be easy to digest. The messages could come by way of quilting, or a poem. These are all things that have shaped our black culture.” —Dominique McFall, biological sciences and public health.

“What surprised me was just how overt racism still is in the south, in some instances. We went by some confederate monuments. One man walked in the middle of the street so he wouldn’t walk on the sidewalk with us. I also noticed that almost everywhere we were, the lower level jobs were black and the higher level manager jobs were all white.” —Taylor Ronnebaum, political science major.

“I’m the PR chair of the Black Student Union and I really liked the fact that I had the trip to go on and make it a highlight for our page on Instagram to help with recruiting students and let them know about opportunities. A lot of things we saw were connected to a university. We saw a monument for Rosa Parks that was dedicated by Alpha Kappa Alpha sorority. She’s an honorary member of Alpha Kappa Alpha.” —Da’von Hicks, social work.

Sarah Collins Rudolph

The students met Sarah Collins Rudolph, a survivor of the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing, which killed four little girls in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1963. She was 12 years old at the time of the attack and suffered severe injuries. Her sister Addie Mae was one of the victims. Snipe has written a biography of Collins Rudolph called “The 5th Little Girl.”

“I was born and raised in Spain; I came to the United States when I was 46 years old, so I did not know many of the leading men and women during the Civil Rights Movement in the U.S. The most moving part of the trip was meeting Sarah Collins Rudolph. Listening to Mrs. Collins Rudolph, a real person who was at that same place, at the same time where a horrible historical event took place, one can understand better that those girls were human beings and each one of them could now be a woman with a complete life, family, if a racist terrorist had not taken their lives in 1963.” –Francisco Marques, graduate student in humanities.

Sarah Collins Rudolph, a survivor of the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing in 1963, shared her experiences with Wright State students on the Civil Rights Pilgrimage.

National Memorial for Peace and Justice, Montgomery, Alabama

Students visited the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, the nation’s first memorial to victims of lynching, and the related Legacy Museum. The memorial and museum were built by the Equal Justice Initiative, founded by Bryan Stevenson, an acclaimed public interest lawyer. The outdoor memorial features many large pillars, each signifying an event of lynching, most representing multiple casualties.

“There are pillars that say ‘Unknown.’ Hundreds of pillars … thousands of people. I don’t know how families would deal with it at that time. They’re just marked as an unknown.” —Alissa Reese, criminal justice major and sociology minor. She was looking forward to the class and pilgrimage experience to reconnect with her family roots in Alabama.

“I was specifically looking at it through the lens of how art is used to tell the story of the black freedom movement. The lynching museum was phenomenal in how art was used symbolically. It was striking how absent whiteness was… and the culpability. And the way the art was integrated into the Whitney Plantation was phenomenal. Statues of enslaved children were placed in different parts. Instead of focusing on black pain, there were children just existing, and the simplicity of silent children, frozen in time.” —Gail Cyan, graduate student in humanities.

“My most memorable moment was at the lynching museum and seeing all the reasons they got hung. They hanged one man for annoying a white woman.” —Imani Tucker, social work.

“It was interesting to see some of the things people got lynched for, such as writing a letter to a white person. It was a lot to take in. We still suffer as a people. It was amazing that people could get away with those horrific murders. I’m glad I experienced this trip. It’s a real eye-opener.” —Willis Blackshear, political science.

“There were states that I didn’t even consider to be part of lynching, such as Utah and Florida. That really showed me how much African American history is ignored. I would never have known lynching went out as far as Utah.” —Imani Foster, African American studies.

“I found a lot of places in Mississippi where lynching took place. I have generations of family that lived there, so you really don’t know if they were there.” —Tyler Willis, marketing.

“The way it’s designed with all the pillars hanging down that represents the person being hung. It’s symbolic. It brought me to tears. But it was a rough part of the trip.” —Maya Riley, political science.

The Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration, Montgomery, Alabama

Students toured the Legacy Museum, which details America’s history of racial injustice. It was built on a site where enslaved people were once warehoused.

“I enjoyed reading the facts about how African American history was shaped from slavery to civil rights. There were great analogies of how people felt at that time.” —Trenton Miller, marketing.

“The Legacy Museum did a great job of showing the struggle that is still very present. It showed where you had the families broken up on the ship. You see the lasting impact of those things. I don’t think the civil rights movement is finished. I personally think we have transitioned what the civil rights movement looks like.” —Sterling Rutledge, African American studies; political science and history minors.

Mississippi Civil Rights Museum, Jackson, Mississippi

Students also visited the new Mississippi Civil Rights Museum, which opened in December 2017 in Jackson, Mississippi.

“I attended the pilgrimage as a freshman, and more recently as a junior and they were both fantastic educational experiences. This year, the most moving part was meeting one of the youngest freedom riders, Hezekiah Watkins. He started when he was 13. He wasn’t even supposed to be there. He got arrested just for watching.” — Precious Claytor, social work.

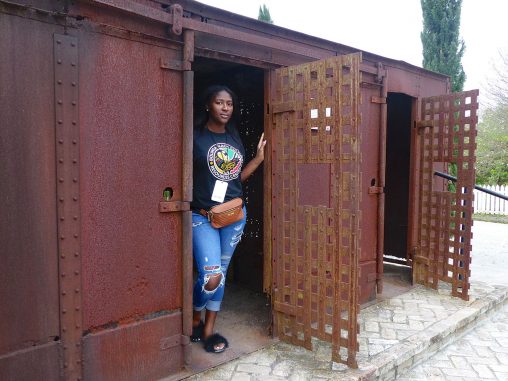

Chanell Murray, a Wright State student majoring in education, explored a cell for the enslaved at the Whitney Plantation in Louisiana.

Whitney Plantation, Edgard, Louisiana

“At our last destination on the pilgrimage, the Whitney Plantation, I was left with a quote that beautifully encapsulated the entire trip. From my conversation with the historian/tour director at the site, I was made aware of the importance of how we remember people. We got on the topic because I admired how she commonly referred to slaves as ‘people enslaved.’ People are not the positions that they are in, especially predicaments that they are forced in. Remembering figures accurately begins with how we refer to them.” –Savannah Jackson, motion pictures.

“It was like you walked in and you were on a plantation. You can see the open field and know people were really out there doing work in the fields. It almost made you tear up that my people did that and didn’t get paid for it.” —Maya Riley, political science.

“I was raised in a culture distinct from most American culture. I was born in India and moved here before I turn one. The visit to the plantation was far more emotional because you saw where things happened. You can put yourself in the shoes of the people there.” —Aashish Bharadwaj, computer science.

“I was moved at the Whitney Plantation when I went into the slave houses. It was amazing what they went through just to harvest the sugar cane. They lived in these little huts with nothing in them.” —Susan Turner, social work.

“Our tour guide was talking about slave owners having relations with the enslaved. If we don’t own our own bodies, we can’t give them away freely, so regardless of these slave relations, they are immoral.” —Jasmine Howell, organization leadership with African American studies minor.

Congo Square, New Orleans

The pilgrimage also made a stop at Congo Square, a park that was used as a meeting ground and heralds the birthplace of jazz.

“I admire the fact that so much African spirituality was still there. I was happy when we went to Congo Square. A tour guide said when slaves would do something, they would dance. The dances would mean certain things. He invited us to join the tour and dance with him. It was a song to honor the ancestors.” —Shaquetta Morris, graduate student in student affairs.

More information about Wright State’s Civil Rights Pilgrimage can be found on the Bolinga Center’s website.

Wright State alum Lindsay Aitchison fulfills childhood space-agency dream

Wright State alum Lindsay Aitchison fulfills childhood space-agency dream  Wright State business professor, alumnus honored by regional technology organizations

Wright State business professor, alumnus honored by regional technology organizations  Wright State University Foundation awards 11 Students First Fund projects

Wright State University Foundation awards 11 Students First Fund projects  Gov. DeWine reappoints Board Treasurer Beth Ferris and names student Ella Vaught to Wright State Board of Trustees

Gov. DeWine reappoints Board Treasurer Beth Ferris and names student Ella Vaught to Wright State Board of Trustees  Joe Gruenberg’s 40-Year support for Wright State celebrated with Honorary Alumnus Award

Joe Gruenberg’s 40-Year support for Wright State celebrated with Honorary Alumnus Award