On a dark and foggy night in the Swaziland bush, The Luke Commission is on a quest—a quest to find a young mother and her two children, ages 5 and 6. The family had been at The Luke Commission’s clinic earlier in the day, where all three had tested positive for HIV.

Before the doctors could get the family started on a treatment plan of anti-retrovirals, the mother and her two children disappeared. After enlisting the help of the local police, The Luke Commission co-founder Echo VanderWal and one of her Swazi team members get into the back of a police van.

The police drive until the road ends. Everyone gets out of the van and walks through the bush. When they arrive at the family’s mud and stick hut, all they can hear is coughing inside.

“It was the obvious TB cough,” Echo recalls.

“We need you to come back,” they tell the mother. The father, who had not been at the clinic earlier, appears.

One by one, they carry out each sleeping child. It isn’t until they get into the light that Echo sees how sick the family really is.

Only the 11-year-old girl is not positive. The other three children, mother, and father all screen positive for TB.

Within a month, no one is coughing. The TB treatments have worked. An HIV treatment regimen is also under way.

“It is just amazing to see the difference in that family,” says Echo. “The mother told us, ‘You came and took us from the grave. We would have been dead if you weren’t there.’”

From Wright State to Swaziland

Harry VanderWal wanted to be a calculus professor. But when he decided to go overseas, he realized that becoming a doctor would be a better way to serve people in other countries.

After graduating from Cedarville College, Harry enrolled in Wright State University’s Boonshoft School of Medicine. His wife Echo, also a Cedarville graduate, went to the Kettering College of Medical Arts to become a physician’s assistant.

Harry chose Wright State for its community-based medical program. “I really appreciated that,” he said. “I was also accepted at the University of Cincinnati and Ohio State, but chose Wright State for that purpose.”

Working in four different hospitals as a resident, Harry developed a diverse base of knowledge and experience. He graduated in 2002 and completed his residency in internal medicine and pediatrics in 2006.

During Harry’s third year of medical school, Echo gave birth to triplets—Zebadiah, Jacob, and Luke—now age 9. The VanderWal’s fourth son, Zion, is 6 years old.

“Having triplets set the stage for working overseas,” said Echo. “We learned how to multitask and not stress about the little things.”

In 2004, the VanderWals traveled to Swaziland, a country in southern Africa with the highest rate of HIV and AIDS in the world. By 2012, 20 percent of the population will be orphans under the age of 17.

When they arrived in Swaziland, the VanderWals noticed a visible gap in available health care services between the cities and rural areas. In a country where 70 percent of the population lives on less than one dollar per day, people are forced to choose between food and health care.

“If you don’t have money for food that day, are you going to have money for transport to go from your home to the city for health care?” said Echo. “We realized right away that people who lived in rural areas—who are usually children, grandmothers who are taking care of the children, unemployed people, and the very, very sick—do not have money to access health care.”

When the VanderWals made their second trip to Swaziland in 2005, they felt a calling to make their home there and to provide health care to those who could not afford it. Harry was still working on his residency at Wright State, so the VanderWals used this time to begin building the infrastructure for The Luke Commission.

When Harry completed his residency in 2006, the VanderWals moved to Swaziland and began forming relationships with local communities. As Echo explained, “Relationships are the currency of Africa. If you don’t build relationships, you will not have a real impact.”

Providing care and compassion

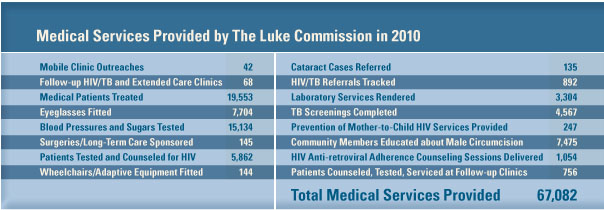

Since its inception, The Luke Commission has provided comprehensive health care to 100,000 patients in more than 200 remote locations. In 2010 alone, they provided 67,000 medical services and traveled 13,000 miles.

At every site, The Luke Commission assesses the health care needs of 600 to 1,000 people. A team of highly trained Swazis handles the preliminary triage, and Harry treats an average of 450 patients per day. The Swazi team provides HIV counseling to the 150 to 200 people who are tested at each clinic.

The disabled receive wheelchairs. People with vision problems are diagnosed and fitted with eyeglasses. Orphans are clothed. School children receive school supplies and Operation Christmas Child gifts.

“We are helping them with today’s problems,” said Harry. “We are helping them with today’s aches and pains and today’s coughs and rashes.”

As patients are being treated for other problems, they are offered testing for HIV. Unlike other facilities in Swaziland, where there is a separate line for HIV testing, The Luke Commission provides comprehensive health care.

“It’s been very exciting to see the way they have embraced testing,” said Echo. Since 80 percent of those who are HIV positive are also infected with TB, The Luke Commission also screens for tuberculosis.

The VanderWals are quick to praise the work many other organizations are doing in Swaziland. “We’re filling a niche that no one else is really doing as far as getting into the rural areas,” Harry explained. “We piggyback on the work people are doing in the cities and place people who are very sick into those programs or into the government clinics.”

The VanderWals also work hand-in-hand with the Swazi people. They have a team of 15 Swazis who assist with all aspects of The Luke Commission’s operations.

“They’re in the foreground now and we’re in the background. That is an amazing picture,” said Echo. “Harry and I stand back sometimes and watch and think ‘we’re watching a miracle.’ The Swazis can impact their own people in a way that we never could as outsiders.”

When the VanderWals are at home in the city of Manzini, people line up outside their front door for treatment. Twice a week, The Luke Commission team travels over mountains and savannahs, often on dirt roads, for as long as 90 minutes to three hours to reach people in rural areas. Working well into the night, they use generators and construction lighting to see. They do not leave until every patient has been treated.

Along for the journey are the couple’s four sons. The boys help load and unload supplies for the clinics and often sing in SiSwati for the crowds. They are schooled remotely by Florida Pensacola Christian School and do their homework in the transport vehicles on the way to the clinics.

“Kids bridge cultural barriers in a way you never could,” said Echo. “Kids are a universal language.”

Help from the Miami Valley

The VanderWals travel to the United States and Canada in November and December, during Swaziland’s rainy season, for speaking engagements and other events to raise money for The Luke Commission.

Christian Life Center (CLC) in Dayton is one of The Luke Commission’s major supporters.

Paul Carlson, who formerly served as associate dean for student affairs and admissions in the Boonshoft School of Medicine, is a member of CLC. Carlson knew the VanderWals when Harry was in medical school and he visited a Luke Commission clinic during one of his three trips to Swaziland.

“They are making an enormous difference. The number of people that they help in any given trip out into the bush is just phenomenal,” said Carlson. “The VanderWals are just a terrific family and couple, and what they do over there is absolutely amazing.”

CLC has pledged $125,000 toward construction of The Luke Commission’s “miracle campus,” which will include an extended care and treatment facility, storage facilities for vehicles and medical supplies, and housing for the VanderWals, their staff, volunteers, and patients. The VanderWals hope to build phase one by the end of this year.

“We’re thankful for all the pieces and parts that people have played so far to help us get to where we are,” said Harry.

In a country where people have a life expectancy of only 32 years, thousands of Swazis are being healed with the kindness, compassion, and care that only The Luke Commission can provide.

As Echo said, “We love the people and we want to see them have hope and health.”

- Wright State Boonshoft School of Medicine graduate Harry VanderWal and his wife, Echo, founded The Luke Commission to provide compassionate medicine to the people of Swaziland—a country with the highest rate of HIV and AIDS in the world.

- A Swazi child and Echo VanderWal embrace.

- The VanderWals on a recent visit to Dayton—Zebediah, Jacob, Echo, Zion, Harry, and Luke.

- In 2010, The Luke Commission provided more than 67,000 medical services and traveled 13,000 miles.

- At every site, The Luke Commission assesses the health care needs of 600 to 1,000 people. A team of highly trained Swazis handles the preliminary triage, and Harry treats an average of 450 patients per day.

- A young Swazi child with Luke VanderWal. By 2012, 20 percent of the Swazi population will be orphans under the age of 17.

- Twice a week, The Luke Commission team travels over mountains and savannahs, often on dirt roads, for as long as 90 minutes to three hours to reach people in rural areas.

- Since its inception, The Luke Commission has provided comprehensive health care to 100,000 patients in more than 200 remote locations.

Walking through open doors

Walking through open doors  Adventures await

Adventures await  Wright State to expand nursing facilities to meet workforce needs and prepare more graduates for in-demand careers

Wright State to expand nursing facilities to meet workforce needs and prepare more graduates for in-demand careers  Wright State student-athletes make a lasting impact on local family with more to come

Wright State student-athletes make a lasting impact on local family with more to come  Wright State names Rajneesh Suri dean of Raj Soin College of Business

Wright State names Rajneesh Suri dean of Raj Soin College of Business