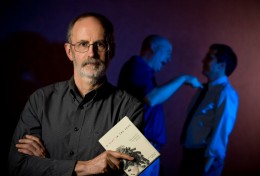

Philosophy Professor William Irvine examines why we should overcome inclinations to hurt others in A Slap in the Face: Why Insults Hurt—And Why They Shouldn’t.

Words have incredible power. “Someone can, with 10 words spoken in 10 seconds, destroy a relationship that’s lasted for 10 years,” says William Irvine, Ph.D., professor of philosophy.

Irvine examines how words can hurt us, and why we shouldn’t let them, in his latest book, A Slap in the Face: Why Insults Hurt—And Why They Shouldn’t, published by Oxford University Press.

To insult someone, said Irvine, is to “say or do something that causes someone else to experience pain,” whether it is done intentionally or unintentionally. According to this definition, you can even insult someone by doing nothing, including, for instance, not shaking a proffered hand or not acknowledging a gift.

As he researched the book, Irvine collected insults from every insult book he could get his hands on.

He says repartee is the highest form of insult because it requires you to be verbally adroit and think on your feet. He cites Winston Churchill and Oscar Wilde as two experts of repartee.

One example of repartee is an exchange between Lady Nancy Astor and Churchill, in which Astor said, “If you were my husband, I would put poison in your coffee.” Churchill’s response: “If you were my wife, I would drink it!”

Irvine found that insults have been around throughout human history, though some consider the Elizabethan period the “golden age of insults.” At that time, it was common to deliver long verbal insults. Today, he says, people are less articulate, less colorful and more prone to rely on using vulgar language or gestures.

The act of insulting others, Irvine says, is hard-wired into humans. It starts with our natural need to belong to a group for our own survival. Once part of a group, we try to rise within its social hierarchy in order to flourish.

He calls the desire to rise in society the “social hierarchy game.” Wolves and dogs rise within their social circles through physical conflict. Because humans evolved brains and language, we use words and gestures. We try to rise in society by putting others in their place, Irvine says, by insulting and causing them pain.

People can stop playing this game, Irvine says, by becoming an insult pacifist and responding to insults in nonaggressive ways. This includes simply ignoring the insult or responding with self-deprecating humor, thereby insulting yourself even worse than the original insulter did.

“If you want to be a happy individual, you will have to learn how not to play the social hierarchy game,” Irvine said. “You’ll have to rise above it and reach the stage at which, although you watch other people play it, you don’t play it yourself. Reaching this stage will take effort, though.”

He encourages those practicing insult pacifism not just to shrug off an insult, but also to reflect on whether it contains a grain of truth. “Your friends don’t tell you your shortcomings. Your enemies have no problem at all doing so,” he said.

Irvine’s research has led him to practice insult pacifism. He closely monitors his tendencies to insult others and to promote himself. He has found that conversations are filled with self-promotion, which he considers another strategy in the social hierarchy game.

As he examined his own conversations, he said, “I found I was simply waiting for the other person to stop talking so I could start self-promoting again.” He has subsequently devoted himself to reducing his self-promotional activities. “There’s still lots of room for improvement!” he said.

One particularly insidious insult that Irvine uncovered in his research is the second-hand insult, in which you tell someone an insult that originated from a third-party.

“It’s a way of inflicting pain on somebody, but with complete deniability,” Irvine said, adding, “We want to put other people in their place, and this is a safe way to do it.”

Oscar Levant, a writer, musician and actor, knew all about second-hand insults. He once said that he never had to read bad reviews of his work because his friends always told him about them.

A Slap in the Face grew out of research Irvine did for his previous book, A Guide to the Good Life: The Ancient Art of Stoic Joy, published in 2008. He planned to include a chapter on insults in that book, but the chapter kept growing until he realized it needed to be its own book.

Stoic philosophers, Irvine said, examined our daily conduct and took particular interest in insults and how to reply to them. “They realized that, first, we’re going to be miserable if we aren’t around other people, and second, if we are around other people they’re going to insult us,” he said.

Irvine, who has taught at Wright State for 30 years, is also the author of On Desire: Why We Want What We Want. He is working on a new book exploring moments of insight in different fields, like science, art, religion and morality.

“I follow my curiosity,” he said. “What I find is that almost everything, when you look at it closely, turns out to be more interesting than you originally thought.”

Walking through open doors

Walking through open doors  Adventures await

Adventures await  Wright State to expand nursing facilities to meet workforce needs and prepare more graduates for in-demand careers

Wright State to expand nursing facilities to meet workforce needs and prepare more graduates for in-demand careers  Wright State student-athletes make a lasting impact on local family with more to come

Wright State student-athletes make a lasting impact on local family with more to come  Wright State names Rajneesh Suri dean of Raj Soin College of Business

Wright State names Rajneesh Suri dean of Raj Soin College of Business