The chance to participate in an official NASA mission at the Johnson Space Center in Houston was a “dream come true” for 2015 Wright State University graduate Emmanuel Urquieta.

Urquieta, who earned a master’s degree in aerospace medicine from the Wright State Boonshoft School of Medicine, also hopes it will help him achieve one of his career goals: working for the space agency as a flight surgeon.

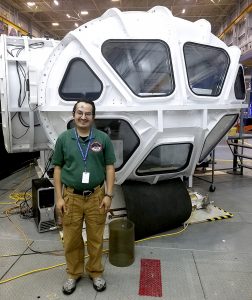

For 30 days last summer, Urquieta and three other crewmembers were confined to a simulated spacecraft to help NASA study the isolation and stresses of deep space travel. The mission took place in the Human Exploration Research Analog (HERA), a modular, three-story research habitat featuring an airlock, medical station, work area, flight deck, four bunks, a galley, and a hygiene module.

The module is used by NASA’s Human Research Program to investigate ways to help the agency move from lower-Earth orbit to deep space explorations. The crew went through the procedures of a real deep space mission without leaving the building. They had the same schedule as the astronauts on the International Space Station and used the same iPad apps for work and for monitoring their health and diet.

Originally from Mexico City, Urquieta has always been interested in space and airplanes, thanks in part to his father, who is an aviation engineer. “I’ve always been around the aviation environment,” said Urquieta, who has a private pilot’s license.

After earning his medical degree from Anahuac University School of Medicine Faculty of Health Sciences in Mexico, he stayed at Anahuac University as an epidemiology assistant professor. He’s also worked as a flight surgeon for the Mexico City Police Department Helicopter Emergency Medical Services.

He hopes to return to the Boonshoft School of Medicine for a residency in aerospace medicine and eventually return to the Johnson Space Center as a flight surgeon.

Urquieta used virtual reality goggles and a hand controller to simulate extravehicular activities on an asteroid.

A flight surgeon plays an important role in a space mission. Typically assigned to one astronaut, the physician follows the astronaut through his or her training, monitors the astronaut’s health during the mission from Mission Control, and provides care after the mission is completed.

“The flight surgeon is like the family doctor of the astronaut during the mission,” Urquieta said.

That’s what made Urquieta’s own mission such a valuable experience. “When I’m a flight surgeon, it’s going to let me take care of them in a better way because I will know exactly what they are going through,” he said. “I’ll have that hands-on experience. I think from the professional and personal points of view this was a great experience.”

Each day of Urquieta’s mission began at 7 a.m. and ended at 11 p.m., ensuring the crewmembers were well rested for the following day’s activities. In between, the crew’s schedules were planned almost to the minute with training, experiments, other scientific activities, and physical exercise. They also held planning meetings with Mission Control twice a day and spent the weekends housekeeping and relaxing by watching movies.

They were allowed to talk to their families for 30 minutes once a week, though the crew had to leave their cellphones behind before entering the module.

During the mission, the crew used virtual reality goggles and hand controllers to simulate extravehicular activities on Geographos 1620, a Mars-crossing asteroid. After a simulated journey on a space exploration vehicle to the asteroid, Urquieta and another crewmember took samples during a simulated spacewalk.

“They give us different locations on the asteroid to retrieve rocks and soil samples, like they would on a real mission,” he said.

The goggles provided a 360-degree view of the asteroid and a “perfectly simulated and rendered graphic representation” of its surface, Urquieta said.

After the activity, the crewmembers simulated the processing of the soil and rocks they collected virtually. They also conducted experiments to grow plants and brine shrimp as well as biomedical and psychological experiments.

Urquieta and the other crewmembers also trained with a simulator of a robot arm used on the space station that can grab items like satellites, tools, and supplies. Astronauts on the space station also train on the simulator.

The HERA module provides a high-fidelity research space for scientists to assess risks and gaps associated with human performance during space exploration by simulating isolation, confinement, and remote conditions. Researchers outside the module collect data on team dynamics, conflict resolution, and the effects of extended isolation and confinement. Studies may focus on behavioral health and performance, communication and autonomy, human factors, and medical capabilities during exploration. It also gives researchers a chance to test new technology and hardware.

For instance, the crew tested two astronaut watches to help NASA study whether a new model is an upgrade over those now used on the International Space Station. They also tested a new iPad app that tracks the food and liquids astronauts consume.

Since the mission simulated a journey to Mars, the crew experienced communication delays with Mission Control over the course of their confinement. The crew then simulated emergencies to help researchers better understand how those delays impacted communication in certain situations.

“These analog missions help to answer a lot of questions about how you handle emergencies, how you handle special situations with very long time delays,” Urquieta said.

In addition to the four-member crew, more than 50 people supported the mission. Mission Control was staffed around the clock and a flight surgeon was always on call. “There are a lot of people behind the mission who make it the way it is,” Urquieta said.

For Urquieta, it was easy to give up a month of his life to contribute something for the future of space exploration.

“Thirty days sounds like a lot, but it went so fast,” he said. “I’ve wanted to do this all my life. It was like a dream doing this.”

Wright State to host Big Hoopla STEM Challenge on March 15

Wright State to host Big Hoopla STEM Challenge on March 15  Regional Workforce Summit at Wright State’s Lake Campus connects students, employers and community leaders

Regional Workforce Summit at Wright State’s Lake Campus connects students, employers and community leaders  Ready for take off

Ready for take off  A foundation of support

A foundation of support  Wake-up call

Wake-up call