The events of last May were a wake-up call to many Americans, while many others saw the faintest glimmer of hope following decades upon decades of repeated turmoil and heartache.

The time for being silent is over. We will confront this head on. History is no longer on repeat. The deep pain felt by the Black community has hopefully seen its last breath on a long path toward healing. Building up a better community is imperative—one that fosters an environment of inclusivity, empowerment, and respect.

It is time to stand up and listen to our neighbors, friends, students, faculty, staff, and alumni. In our amazingly diverse and seemingly infinite community, there are agents of change—individuals who define what it is to make a difference for those around them.

The following alumni and Wright State community members are confronting racism and all of its manifestations.

They have made a dedicated responsibility to help their communities move forward—a responsibility not taken lightly.

They are activists and educators, visionaries and advocates, innovators and radicals.

They are the changemakers.

The hard conversations

Kenneth Bryant, Ph.D. ’09, is helping students, faculty, and the greater community tackle issues surrounding systemic racism

Every week Kenneth Bryant, Ph.D., sends messages to offer encouragement and perspective to his students at the University of Texas–Tyler.

As a political science assistant professor involved in examining and dismantling systemic racism and working to help foster an inclusive community, he wants all of his students to know, “They’re here, and they belong here,” he said. “I don’t want to allow that imposter syndrome to paralyze them or to sabotage their progress.”

Bryant—who graduated with a bachelor’s degree in political science in 2009—wants to make sure students of color feel seen and welcome.

“I’ve been in [their] shoes. You don’t have to go through it alone; you don’t have to be isolated. You do yourself a disservice if you don’t reach out,” he said.

In the classroom, he explores topics that include race and ethnicity; mass media and American politics; political behavior; the presidency; and the functions of American government. He also researches public responses and opinions on protesting.

“I am intrigued as a scholar and academic,” he said.

While he has always been concerned about social justice, the nationwide protests over the death of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police particularly struck a nerve last summer for Bryant.

“I was completely and utterly paralyzed by the trauma of another Black man murdered on the streets, and not knowing what to do, where to go, and where to process that,” he said.

But for a teacher and mentor who sparks important conversations, talking helped.

An interview with the nonprofit media outlet The Tyler Loop helped galvanize him into action. During a time when communities across the country were examining their own systemic racism, participating in the interview, titled “What It Means to Be Antiracist,” helped him work through his trauma.

He talked about the inspiration from students. “We talk about different types of identities and their role in politics in America,” he said in the article. “Students engage with each other in the debate, and they’re not attacking each other. They’re attacking the arguments, and they’re knocking these really weak or dangerous arguments flat in the classroom. That’s wonderful.”

The antiracism work is far from over—he knows that—but says he feels encouraged by the receptiveness to change.

“If I’m going to be a gatekeeper, as a professor, I’m going to keep perspective,” Bryant said. “Remember where you came from…folks who come through, make sure to open doors for them.” —Sarah Ravits

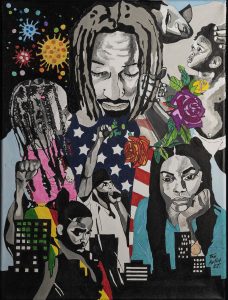

Art: An understanding

Artist Shirley Tucker ’89 created the cover for this issue of Wright State Magazine

The cover of this issue features artwork, titled “Faces of Courage,” by alumna Shirley Tucker ’89, a professional artist who serves as the head facilitator of the Montgomery County Juvenile Court’s art program, Helping Adolescents Achieve Long-term Objectives (HAALO).

HAALO is a collaboration between the court and the K12 Gallery & TEJAS in Dayton, an artist-centered regional visual arts center offering programs for area youth. The majority of youth participating in the program are Black, between the ages of 12 and 18. Their work has appeared across the Dayton region in over 20 murals painted on building exteriors and at local community centers. Tucker has worked for the juvenile court for 30 years.

She has gifted the artwork to the Wright State Alumni Association.

What was your inspiration behind this piece for the cover?

What really inspired me is what we have going on in our community. With George Floyd, Breonna Taylor…right now our country is just an upside-down war. With the pandemic, all the [minority] lives lost, and the people who are struggling. I just started thinking about the title of this story and actually what it represents; and how can I visually show that. COVID-19, poverty, loss of jobs, unemployment, racism, discrimination, police violence, all those things are affecting our community and country right now.

Minority communities who have experienced decades of systemic racism are now feeling the effects of COVID the hardest. How can we move forward?

It’s not something that you can put a Band-Aid on and cover up. That wound is still not going to be healed. It’s not going to close completely until it gets the care that it needs. That’s the same thing with our society, our community. How can we move forward as a community and work together? There has to be change. In order for there to be change, everybody has to come together—people from all races.

How do you think art can fight racism or racial injustice?

I don’t know if we can actually change it. I think sometimes people just don’t have an understanding—they stereotype and form an opinion. Sometimes it’s just a matter of things being introduced to you. That’s what art can do. We all see things differently. I see one thing; you see it differently. What we’re all looking for is something there that we can identify with, something that will get us to think about what it is that the artist is trying to say. —Nicole L. Craw

Catching that fish

Robert “Bo” Chilton ’94, ’00 activist and nonprofit leader, fights for the stability of Columbus citizens

Robert “Bo” Chilton leads with a familiar philosophy of giving people more to help regain power in their lives.

“We think about our work in using the parable, if you give a person fish, they eat for a day. You teach the person to fish they will eat for a lifetime,” he said. “But, even with that, I challenge the function and say you’re not going to eat for a lifetime unless there’s some pond, river, or sea from which to catch that fish.”

Chilton serves as CEO of IMPACT Community Action, an organization that serves over 25,000 citizens annually in the Columbus area. From homelessness prevention to rent assistance to helping individuals obtain and sustain employment, IMPACT is focused on moving people from crisis to stability.

The majority of the community members IMPACT serves are Black and people of color living in underserved communities around Columbus—a population severely impacted by COVID-19 in recent months.

IMPACT has been working with hundreds of residents to assist in potential evictions.

“Franklin County is one of the worst in the nation, in terms of mass evictions per capita. [They] evict over 18,000 people annually, but that’s where we’re intervening,” he said.

One way in which Chilton sees possible change in his community is through changes to the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA), a federal law enacted in 1977 designed to encourage banks to help meet the credit needs of borrowers in low- and moderate-income neighborhoods.

“When we start talking about the CRA, obviously there’s been systemic and historical racism that has contributed to redlining and putting segments of our society out of the shared prosperity that should be available to all as an American citizen,” said Chilton.

An example, he said, is that banks can count loans for improvements to projects that sit in poor neighborhoods.

“It might be possible for the banks that financed the [Columbus] Crew Stadium to claim credit for investing in low-income communities,” he said. “This type of investing contributes to gentrification and displacement of low-income people, not at all what the CRA was intended to do.”

Another piece of legislation he sees as a stepping stone is Issue 2—which voters overwhelmingly supported in November—creating the Civilian Review Board for the Columbus Division of Police.

Chilton said he doesn’t like the term “defund the police,” but instead wants to see a stronger relationship with the community and police together.

He said, “I really don’t like the idea that the whole Black Lives Matter is in juxtaposition with the police, because then you get into a back and forth between Black Lives Matter and Blue Lives Matter, and it’s not an either/or.” —Sarah Cavender ’20

Louder than words

Poet Sierra Leone ’06, ’19 hopes work will shed light on trauma of racism

Sierra Leone contains multitudes. The artist, entrepreneur, activist, poet, and mother is a native of Toledo who spent part of her childhood in Louisiana. Traveling between the two distinct regions helped her develop a strong sense of community early on in life—and a deep sense of reflection.

“Family, community, and tribe” are her priorities to this day, she said.

As a youth, Leone said, she always loved to create and “connect to things around me and in my world, and tell stories.” She says she believes in the power of shared experiences and is an avid storyteller who connects with audiences through live performances, including those at the Victoria Theatre in Dayton.

She is the founder of Oral Funk Poetry, a creative arts organization that connects her to other artists and has an educational component that allows her to mentor young children who might not otherwise have access to fine arts.

Leone’s motivation to help others comes from her own experiences as a Black woman. She says she always felt uplifted by encouragement from mentors, including faculty and fellow students at Wright State.

“Being better together,” is one of her goals as a person deeply committed to advocating for others, particularly those in marginalized communities. “Along the way, I grew to build a community of mentors who supported me,” she said.

Her favorite way to give back to the community and foster creativity has been done through “creating a space for urban, creative artists,” she said.

In the last several months, as protests gave new momentum to the Black Lives Matter movement, Leone says this has been incorporated into her art.

“I’ve been making art with my team and community and world to shed light on these traumas and the impact of racism and inequality and divisiveness that lives in America—while also celebrating the journey of minorities,” she said. —Sarah Ravits

A healthy outcome

Dr. Michael Robertson ’11, ’14, ’16 wants to see health care focus more on keeping his patients healthy

Dr. Michael Robertson says he believes in being an advocate for his patients. The Cincinnati native is a family physician with Premier Health’s Middletown Family Practice in Franklin, Ohio.

“I went into family medicine to make sure patients don’t fall through the cracks,” he said.

Robertson says that the issue of racial disparities in health care is problematic in this country, and is unfortunately something he has seen through his time as a physician. But, he says, the issues go beyond the actual care given—they extend to health outcomes and patient experience. Health outcomes focus on the result of care and are a big determinant of the patient experience.

Health outcomes have discrepancies when it comes to race, he explains.

“Illnesses such as diabetes, hypertension, heart disease, and high cholesterol are increased in minority communities,” Robertson said. “They are more likely to be poorly controlled, so upon diagnosis are more severe, or are progressing into other health problems. Cancers tend to get diagnosed in later stages too, at which point they are harder to control and treat.”

Studies have shown patients seeing a provider of the same ethnicity can help health outcomes. Having a physician of the same race improves patient willingness to follow treatment plans, and undergo preventative tests. More African American and Latino physicians are needed—they account for only 5 and 6 percent, respectively, of the physician workforce, in stark contrast to the 13 and 17 percent, respectively, they make up in the U.S. population, based on the last census data.

Robertson also says there needs to be more diversity in clinical trials. Studies have suggested that side-effect profiles, and prevention and screening guidelines for medications, need to be adjusted by demographics.

“Many of our first-line medications are based on Caucasian males, and then extrapolated for females and other ethnicities,” Robertson said.

According to Robertson, the health care system needs to be revamped.

“We do a good job treating the sick, but not of keeping people healthy,” he said.

Robertson said this can be addressed with better integration of public health into routine health care and revising the funding model from insurance companies, putting more emphasis on prevention and wellness. —Lisa Coffey

Care first, education second

Dr. Andre Harris, Sr., FACOG ’02, one of the only Black male OBGYNs in Dayton, cares for his patients and educates his colleagues

Dr. Andre Harris, Sr. is an obstetrician and gynecologist (OBGYN) and chief medical officer with Premier Health’s Atrium Medical Center in Middletown, Ohio. Harris is one of the only Black male OBGYNs with a practice in the city of Dayton and is on the front lines providing care to the underserved.

“I received a National Health Service Corps scholarship to pay for medical school and owed four years of service,” Harris said. “Requirements for the service were to work in a medically underserved community and care for patients despite their ability to pay.” This led to Harris and his wife, Charlotte Harris, R.N., B.S.N., founding Horizon Women’s Healthcare in Dayton in 2006.

Numbers are high nationally for Black mothers who die during childbirth and the postpartum period, and Harris is doing his part to reduce them in Dayton.

“The top reasons for maternal mortality are hypertension and postpartum hemorrhage,” Harris said. “Postpartum hemorrhage can be managed effectively with early detection, education, prophylactic administration of medications, a good relationship between physician and nursing staff, and swift care and management when complications present.”

When it comes to disparity in health care, Harris says providers need to see how biases are affecting the delivery of care, and he believes education can not only help reveal those biases, but their effects as well.

“There are biases and racist beliefs that prevail, yet there is a core of people who have not been educated on white privilege, micro-inequities, and being an ally,” Harris added.

Harris is president of Gem City Medical, Dental, and Pharmaceutical Society, a nonprofit group of minority medical professionals in Dayton who focus on removing causes of discrimination in health care. More recently, providing mentorship to medical students of color at the Wright State University Boonshoft School of Medicine has been a priority.

“It allows these medical students to be in touch with, and bounce things off of, someone who looks like they do and understands where they are coming from,” Harris said.

Harris has been a voice for racism education at Premier Health. He participates in diversity and inclusion committees and hosts virtual discussions about racial injustices in medical history. For example, in the 1950s, African American Henrietta Lacks’ cells were taken without consent or compensation during her own cancer treatment, and became the source of one of the most important cell lines in the history of medical research, eventually leading to the creation of the polio vaccine.

“These frank, educational discussions have opened a lot of eyes,” Harris said.

In recognition of Harris’ contributions to the Dayton medical community, he was presented with the Parity Inc. Top Ten African-American Male award this past year. — Lisa Coffey

We declare Dayton

Mayor Nan Whaley ’09 says racism is a public health crisis

In June, the city of Dayton joined a growing number of major cities in the U.S. in declaring racism a public health crisis.

The Dayton City Commission unanimously approved a resolution saying that racism subjects people of color to hardship and disadvantage in all areas of life. The resolution also stated that racism is responsible for minorities having higher rates of homelessness and incarceration, and thus, poor education and health outcomes.

Alumna and Dayton Mayor Nan Whaley said the city wants to utilize a “collective impact model” to focus on racism issues, similar to how the city has approached confronting the opioid epidemic and other community efforts.

“We’ve seen collective impact models work for other issues in Dayton. So, along with Public Health—Dayton & Montgomery County, we’re actively engaging additional partners to join us in doing this work,” Whaley said.

Whaley emphasized there is a large portion of the Dayton community that is not healthy and not living up to its full potential because of systemic disparities, something the city needs to work to change.

“I think we have a responsibility to address systemic racism and the disparities that it’s created in our community,” she said. —Nicole L. Craw

From agony to action

Rep. Joyce Beatty ’75 fights racial injustice from the front lines

Rep. Joyce Beatty has served as the U.S. Representative for Ohio’s 3rd Congressional District since 2013 and was recently named chair of the Congressional Black Caucus.

This past November, during one of the most heated and highly politicized election cycles in recent memory, she was one of the most outspoken political voices advocating for social justice and national change.

Beatty was also one of the few politicians to walk the front lines and protest with the Black Lives Matter movement.

“I was so proud and honored that people were glad to see an elected official,” she said. “They’re glad to see that we were uniting with students, activists, and others.”

On May 30, she joined a group of demonstrators in downtown Columbus protesting police violence following the killing of George Floyd. The protest turned into a clash with police.

“As the crowd got larger, in my role to try to be helpful, I went across the street where there were some protesters, and some police officers in riot gear came along,” Beatty said.

At the height of the excitement and anger, Beatty said the demonstrators exchanged words with police and the scene turned into chaos, and pepper spray was released into the crowd.

Beatty said the experience opened her eyes to what happens to many others unnecessarily.

“As I was pepper-sprayed and just feeling that burning sensation…that kind of opened my eyes to see what happens to so many people,” said Beatty. “What happened to George Floyd is real—there are disparities within our system. We certainly know that Black people are treated disproportionately differently and we have witnessed that.”

Beatty said she was pleased to see the national attention the movement was getting. “It gives me hope that we will have change,” she said.

One of those points of change, she said, is HR7120, the George Floyd Policing Act, which was introduced in the U.S. House of Representatives in February. The bill includes measures to combat police misconduct, excessive force, and racial bias in policing.

“We have to keep the legislation at the forefront,” she said. “Words matter—we have to put it in words that can educate.”

The Congresswoman is optimistic about the bill, but said there is a need for more education and awareness.

Beatty hopes to challenge others to be engaged and calls the work “agony to action.”

“We’ve had so much agony, with the death of the George Floyds and the Breonna Taylors and, more recently, Casey Goodson, that we don’t want their lives and their deaths to be in vain,” Beatty said. “So, we’re going to go to work, from agony to action. The action of giving everyone a challenge to be engaged, to be more informed.” —Sarah Cavender ’20

Affirming community

The Women’s Center’s Women of Color Student Mentorship and Leadership Cohort

Once a month on Friday afternoons, 15–20 students who self-identify as women of color meet virtually to discuss topics like self-care, campus resources, experiences with discrimination, and building a personal and professional brand. Toward the end of each session, members break into peer-mentorship groups to discuss successes and challenges with a student mentor.

The Women of Color Student Mentorship and Leadership Cohort (WCSMLC) is a mentorship program sponsored by the Women’s Center. The group is inclusive of women who identify as African; Black/African-American; Latina; Hispanic; Southeast, South, East, or West Asian; Pacific Islander; and Native American or Indigenous.

Created in 2016, the program’s goal is to increase belongingness, wellness, persistence, retention, and degree completion for groups of women who are often marginalized and underserved in society and on campus. Students who participate apply to be part of the program and receive a small scholarship from the Pepsi Women’s Empowerment Fund.

The idea for the WCSMLC was inspired by my own experiences as a Black woman navigating undergraduate, graduate, and professional degree experiences with little help, and the added challenges of systemic racism, sexism, and ableism.

Along my journey, I just figured it out by continuously failing, starting again, and succeeding. That journey was not without trauma due to discrimination along the way. The conflation of academic rigor and social inequities made it even more difficult to remain persistent.

This program is my, and the Women’s Center’s, way of ending the cycle of trauma. This semester has proved more difficult for many of the students as they have had to endure the complications of COVID-19 and the continued killing of Black and Brown individuals.

Groups like the WCSMLC are known to foster an inclusive campus environment by offering a safe space of support.

I hope there are continued efforts to create a campus where those who have been harmed, marginalized, and underserved feel they belong and have the capacity to thrive to receive the education they deserve. —Nicole Carter, Ph.D., Director, Women’s Center

Contributions to the Pepsi Women’s Empowerment Scholarship at Wright State can be made by visiting wright.edu/give/pepsiwomenschl.

An anti-racism reading list

Last spring, the Wright State University Libraries staff created an Anti-Racism Resource Guide to provide book recommendations for students and community members seeking more information on anti-racism subjects.

White Fragility: Why It’s so Hard for White People to Talk About Racism By Robin DiAngelo

As a white author writing for a white audience, DiAngelo approaches the difficult aspects of discussing race and the difficulties of having those discussions as a white person. This book addresses the idea of a binary perspective of racism and the way emotional reactions can prevent new understanding and empathy.

So You Want to Talk About Race By Ijeoma Oluo

Oluo explores the complex reality of the racial landscape through 17 chapters, each posing a different question about race. Her writing includes a mix of personal experience, suggestions for shared definitions, and actions to practice anti-racism.

Stamped: Racism, Antiracism, and You: A Remix of the National Book Award-Winning Stamped from the Beginning By Jason Reynolds and Ibram X. Kendi

Jason Reynolds, the National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature, created this “remix” for young adults by working with Ibram X. Kendi’s National Book Award–winning Stamped from the Beginning. This book presents a history of the construct of race, and how the concept of race informs our thinking as a society today. While marketed to young adults, this is a good option for anyone interested in an engaging, fast-paced approach. —Compiled by Wright State University Libraries staff

For more information, view the University Libraries’ Anti-Racism Resource Guide at guides.libraries.wright.edu/anti-racism.

Racial Equity Task Force looks to create change

Many student leaders, faculty, and staff came together last May to confront the issue of racism and how they can make anti-racist work a priority for the entire university.

From these talks, a new task force was created—the Racial Equity Task Force.

The task force has acknowledged there have been prejudices and oppressions experienced by students, faculty, and staff of color and pledged to actively pursue pathways for their safety and success.

Among its leaders are Adrian Williams ’21, student body president; Brian Boyd, Ph.D., associate professor of mathematics education and Faculty Senate vice president; and Carol Mejia-LaPerle, Ph.D., professor of English.

How is the conversation going so far, and what has been discussed as far as progress happening on campus?

AW: The conversation is going very well. Obviously, the goal of the task force is large and will take a long time to complete. We are in discussions with faculty and department heads to get feedback on anti-racist work in every facet of the university, and we [have worked to] advocate with the president for the governor to appoint a diverse new University Board of Trustees member.

BB: Our Policies and Procedures Committee is examining policies and practices that impact students, staff, and faculty. This includes how the “test optional” policies might impact students and how equity work could be recognized as part of service to the university for staff and faculty.

How are we ensuring that students’ voices are being included in these conversations?

AW: As a student myself, I am essentially co-chair of the task force alongside Brian Boyd and have given my input into every aspect of the creation and implementation of the task force. I have invited a number of diverse students from groups across campus to voice their opinions during meetings as well.

CML: We begin every meeting with student voices and we have taken their demands very seriously. Three demands we have heard—more representation in Wright State communications; mentoring throughout their academic journey; and better institutional understanding of the history of racism.

How can we ensure that this task force will result in some action (not just talk)?

AW: The focus of the task force is specific and actionable steps that can effect change, such as directly advocating for a diverse University Board of Trustees appointee. The time for placating statements has long passed, and this task force is committed to producing actual results and measurable outcomes.

CML: Systemic change requires concrete resources and long-term commitment. The task force is working with President Edwards’ Inclusive Excellence initiatives to strongly condemn racial injustice and inequity in all levels of university life.

BB: Students like Adrian have been consistent in their message to the task force—they want specific action. We know that many of the actions will fall to the staff, faculty, and administrators. I want action to be the standard we are held to—I want students, staff, and faculty of color to be able to say that they can see the effects of actions on campus. If they don’t, then we need to do more.

What are some steps alumni can take to further the mission of inclusive excellence at Wright State?

AW: Alumni can support student initiatives and scholarships financially, and stay connected to the alumni network by providing mentorship and internship opportunities.

CML: I would respectfully ask them to demand that the membership of the University Board of Trustees represents the student body. Enabling permanent, structural anti-racist policies starts with representation.

BB: I think alumni can serve as active mentors for our students of color. They can work with our identity centers to provide personal and professional networks for our students. —As told to Nicole L. Craw

How students are standing up

Students have taken their own roles within the fight against systemic racism and implicit bias, especially within the campus community. This nation has seen profound, progressive change in the movements for social justice and civil rights this past year. While the nation stands up, our students have been critical voices for positive change right here at home. We invite you to meet three Wright State students striving for equality and inclusion. —As Told to Nicole L. Craw

Dai’Shanae Moore ’21

Dai’Shanae Moore ’21

Political Science and Sociology

President, Association of Black Business Students

Sigma Gamma Rho

“I’m striving to create change at Wright State by helping to create a safe place for National Pan-Hellenic Council fraternities and sororities to receive plots [safe spaces] on campus. Through my sorority, I serve as an advocate for students of color who don’t feel they have a voice. I want to help our university meet the students of color halfway by building our community to be more effective and opening.”

Tiphani Moss, Psy.M.

Tiphani Moss, Psy.M.

Fourth-year doctoral student, Clinical Psychology

Director of Student Affairs, Student Government Association

“As a therapist, I work with people from diverse cultural backgrounds to help them in improving and maintaining their mental health, and to cope with experiences such as racial trauma. Last semester, as a trainee at a local counseling center, I worked to co-develop and co-facilitate a supportive space to help underrepresented students navigate the transition of completing the Fall Semester at home during the pandemic.”

Chiemeka Okafor ’21

Chiemeka Okafor ’21

Biology

Events Coordinator, Multicultural Association for Pre-Health Students (MAPS)

“It is vital that representation becomes an essential part in our college experience. Having people who look like you, talk like you, and possess similar upbringing as you, through invitation of more speakers and role models for students to relate and look up to…will go a long way in terms of creating an atmosphere that minimizes ethnocentrism while uplifting ideals of cultural relativism.”

Two new scholarships promote equity and inclusion

George Floyd Scholarship

Like most people around the world, Lorraine Hennigen was shocked and distressed by the tragic killing of George Floyd. Floyd’s death on May 25 sparked protests against police brutality throughout the U.S. and across the globe.

As Hennigen watched a live television broadcast of Floyd’s memorial service, she was inspired by the words of Scott Hagan, president of North Central University in Minneapolis, who challenged “every university president in the U.S. to establish your own George Floyd Memorial Scholarship Fund.”

Hennigen, who has three degrees from three universities, wrote to each of her alma maters to encourage them to establish a George Floyd Memorial Scholarship. With each note, she enclosed a check to help start the scholarship. One of those letters landed on the desk of President Sue Edwards.

“For people who are invested in equity and righting the many wrongs of the past, I think this is one small way that we can behave as antiracists,” said Hennigen, who graduated in 1984 with a Master of Education degree.

She hopes the scholarship will help make a college education more affordable and accessible for promising students from underrepresented populations, especially young Black students.

Retain the 9 Scholarship

Like Hennigen, Andrea Kunk and the team at Peerless Technologies Corporation decided to support organizations fighting racial injustice. Kunk, chief financial officer at Peerless and a two-time Wright State graduate, said it was important to look at ways the company could help make a difference locally.

“We have a real passion for supporting Wright State students,” said Kunk, who directed Peerless’ gift to the Retain the 9 Scholarship. “Scholarships are probably the No. 1 avenue to helping support student success and retention.”

Launched in 2017 by Black Men on the Move, the Retain the 9 initiative was established to help retain the 9.9 percent of students on campus who are Black. Since then, Retain the 9 has evolved into a campus-wide initiative to address retention rates for all underrepresented students. A task force identified four key components that contributed to the low retention rates for minority students: personal, cultural, financial, and academic. —Kim Patton

To make an online gift to the George Floyd Memorial Scholarship or the Retain the 9 Scholarship, visit wright.edu/give/georgefloyd or wright.edu/give/retainthe9.

Black voices matter

Dorian Buford ’21, president of the Black Student Union, has been a voice for students in the wake of social injustice

Dorian Buford is an activist. It’s in his blood. His father, Carlos Buford, a well-known local political activist, founded the Dayton chapter of Black Lives Matter.

This summer, after seeing cities across the country march for racial justice, Buford knew he needed more from

Wright State.

As president of the Black Student Union (BSU), together with his members and the Student Government Association, they issued a statement to university administration, asking that the issues of Black students be addressed on the university’s social media channels.

“We wanted our voices to be heard by the faculty and administration,” he said. “Back in April, there was a lot going on at that time, especially on social media.”

Buford said he had seen several other national universities writing posts of support for their Black students on their main social media accounts.

“We weren’t seeing that kind of support,” he said. “Our generation is reliant on social media. That’s how we can seek support from our university.”

After the letter, he said, BSU had several conversations with university leadership and the university started to take the necessary steps to address the issue.

As BSU president, Buford’s goal has been to create a family-like atmosphere for students going through the effects of police violence, the election, and COVID-19.

“The Black community [at Wright State] is small, so, I want all of us to be united,” Buford said. “Make sure our voices are heard, our struggles are addressed.”

In late August, Buford traveled with his father to the March on Washington in Washington, D.C., an event, he said, that helped “unite America for one cause.”

Upon his return, he and other students voiced concern after the Wright State Rock, a symbol of expression and social action on campus, had its message of #BlackLivesMatter painted over.

“The campus rock has been vandalized with hate speech before [in 2016]; someone had painted it with ‘Black Lives Matter,’ but then someone painted ‘White Lives Matter’ on top,” Buford said.

Enraged, BSU members wanted to take action, deciding to host the Black Voices Matter Rally. On October 8, the rally attracted over 150 people, including students, staff, faculty, and administrative leadership.

The event featured speakers, poets, musical performances, and information about racial injustice and voting in the 2020 election. A candlelight vigil recognized 50 victims of police violence.

“I was proud and humbled that we received so much recognition and praise for this much-needed event,” Buford said.

Though there is still work to do, Buford said he has seen improvement on campus.

“I think the university has taken the necessary steps to make sure that we are taken care of, not just the Black community, but all minority groups,” he said. —Sarah Cavender ’20

This article was originally published in the spring 2021 issue of the Wright State Magazine. Find more stories at wright.edu/alumnimag.

Centerville seventh grader wins Wright State University Regional Spelling Bee, advances to 2026 Scripps National Spelling Bee

Centerville seventh grader wins Wright State University Regional Spelling Bee, advances to 2026 Scripps National Spelling Bee  Three Wright State students win full year of tuition during Horizon League Championship game

Three Wright State students win full year of tuition during Horizon League Championship game  Walking through open doors

Walking through open doors  Adventures await

Adventures await  Wright State to expand nursing facilities to meet workforce needs and prepare more graduates for in-demand careers

Wright State to expand nursing facilities to meet workforce needs and prepare more graduates for in-demand careers