Excerpt

Artificial intelligence is disrupting just about every area of life, and local researchers are using the technology in potentially lifesaving ways.

Artificial intelligence is disrupting just about every area of life, and local researchers are using the technology in potentially lifesaving ways.

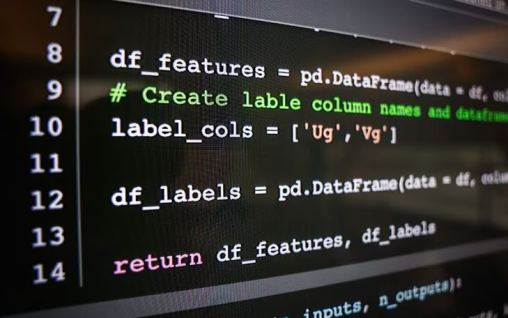

Graduate students under the direction of Tanvi Banerjee, professor of computer science and engineering at Wright State University, are creating their own machine learning models for health care applications. The projects at Wright State range from predicting caregiver burnout for dementia patients to measuring pain in patients with sickle cell disease.

Master’s degree student Tawsik Jawad’s research focuses on developing models to pre-emptively catch self-harming behaviors in anxious pre-teens. Anxiety in childhood can have far-reaching impacts on an individual’s physical and mental health as an adult, and not only would the model be able to analyze patterns of physiological symptoms and behavior, but may be able to alert parents and caregivers before things take a turn for the worse.

Tanvi Banerjee, associate professor of computer science, researches multimodal data fusion and machine learning.

“When we think about proactive measures, it’s hard to do that. I think a model can give us those early warning signs,” Banerjee said. “Worst case, the model is wrong. But best case, it’s right and we are able to do something about it.”

Individualized precision medicine is among several “promising” areas of machine learning that will continue to progress rapidly, said Krishnaprasad Thirunarayan, professor of computer science and engineering at Wright State. Others include disaster response, tracking harmful and deceptive data like spam, phishing and misinformation, recommender systems, speech, image and video processing, autonomous vehicles, and cybersecurity, to name a few.

Banerjee’s research involves preventing burnout in unpaid caregivers for patients with dementia. Usually this is a spouse or a loved one, and taking care of someone with dementia can take an extreme toll, especially if the caregiver themselves have other health conditions or other things going on, Banerjee said.

Wearable fitness trackers measure heart rate, blood pressure and skin temperature, and the patients are asked about their sleep quality, all of which can be used to determine the person’s stress level or heightened emotional state.

“What we can do then is take all these measurements, these signals, these vital signs, and put it into a machine learning model,” Banerjee said. “And if we are able to tie that to different stress levels, different emotion levels, if we’re able to tag that — then the model learns.”

Artificial intelligence and health care is not without its own ethical considerations. It also has the potential to exacerbate medical bias. Many larger AI systems have been trained on datasets fitting one narrow demographic and are less accurate in predicting outcomes for other demographic groups.

For example, a 2019 study published in Science Magazine found that an algorithm commonly used by hospitals to recommend certain people for medical care was less likely to recommend adequate medical treatment for Black patients compared white patients. The algorithm predicted health care costs rather than illness, but unequal access to care means that health care providers spend less money caring for Black patients.

As such, transparency in what data the model is being trained on is paramount, Banerjee said.

“A model is as good as the data we feed into it,” said Banerjee. “The model is not biased, the data are.”

“What are the parameters that we’re feeding into the model? If that information is not provided to us, and if we just blindly use the system, either the system is going to fail, or it’s going to change the trajectories of certain lives forever in a way that it shouldn’t,” she said.

View the original story at daytondailynews.com

Walking through open doors

Walking through open doors  Adventures await

Adventures await  Wright State to expand nursing facilities to meet workforce needs and prepare more graduates for in-demand careers

Wright State to expand nursing facilities to meet workforce needs and prepare more graduates for in-demand careers  Wright State student-athletes make a lasting impact on local family with more to come

Wright State student-athletes make a lasting impact on local family with more to come  Wright State names Rajneesh Suri dean of Raj Soin College of Business

Wright State names Rajneesh Suri dean of Raj Soin College of Business