Detective work is far from uncommon among historians. After years of tireless research, a Wright State professor has unearthed the untold story of a seemingly ordinary colonial woman named Elizabeth Tuttle. But what Ava Chamberlain, Ph.D., associate professor of religion, found was blood, adultery and the roots of an incredible family tree.

Detective work is far from uncommon among historians. After years of tireless research, a Wright State professor has unearthed the untold story of a seemingly ordinary colonial woman named Elizabeth Tuttle. But what Ava Chamberlain, Ph.D., associate professor of religion, found was blood, adultery and the roots of an incredible family tree.

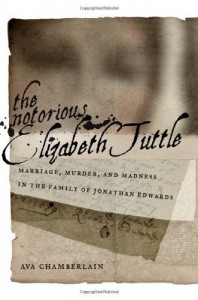

Chamberlain begins her recent publication, The Notorious Elizabeth Tuttle: Marriage, Murder, and Madness in the Family of Jonathan Edwards, by explaining Tuttle’s biggest claim to fame: the relationship to her grandson Edwards, a distinguished Puritan theologian.

“Elizabeth Tuttle has been mentioned in most contemporary biographies of Edwards, but only very briefly and portrayed in a negative light,“ said Chamberlain.

The story of Tuttle, both tragic and turbulent, begins with her husband Richard’s ongoing suspicions of her infidelity.

“After their first child was born—only a couple months after their wedding—Richard began to believe that Elizabeth had cheated on him, and these suspicions resurfaced periodically throughout their marriage,” said Chamberlain.

In the end, it was a combination of these suspicions and Elizabeth’s onsetting madness that drove Richard to divorce. But like most failed relationships, there are two sides: Chamberlain wanted to give Elizabeth a voice by exploring her side of the story.

“In writing this book, I didn’t want to just resurrect Elizabeth Tuttle,” said Chamberlain. “I wanted to look at gender roles for women and how women are represented historically.”

By researching Elizabeth’s alleged madness, Chamberlain found the blood dripping from the Tuttle family tree: one of Elizabeth’s brothers had murdered their sister and another sister had murdered her own teenage son.

Following the delirium of the divorce and deaths, Elizabeth disappears from the history books. Richard remarries and has a number of children—the family he always wanted, according to Chamberlain.

Although Elizabeth vanished from history, her genetic lineage continues to impact the course of history. Jonathan Edwards, Tuttle’s grandson, shaped the First Great Awakening with his revolutionary theology and became the subject of incredible scrutiny in the 19th century. Around this time, the eugenics movement started to pick up steam. Eugenics revolved around the notion that there is a superior gene pool and aimed to promote the reproduction of these superior traits while limiting procreation among those deemed “unfit.”

“In the 19th century, Jonathan Edwards and his descendants were lifted up as the paradigm as the eugenically fit family,” said Chamberlain.

Edwards is related to historical figures such as Winston Churchill, Eleanor Roosevelt, Ulysses S. Grant, and Grover Cleveland. Additionally, his gene pool has been filled with doctors, scholars, lawyers and many other “eugenically superior professionals”.

With all of these “fit” members in Edwards’ family, eugenicists were stumped by Jonathan’s relation to his “notorious” grandmother. Because her history tarnished the impressive branches of Jonathan Edwards’ family tree, those associated with the eugenics movement of the 19th century pigeonholed her as being “crazy” or “promiscuous”.

Eugenics may have lost its validity over time, but the nasty stigma eugenicists gave Elizabeth continued through 20th century biographies of Jonathan Edwards. Through this book, Chamberlain attempts to construct a richer portrait of the woman whose family left such a mark in history.

Centerville seventh grader wins Wright State University Regional Spelling Bee, advances to 2026 Scripps National Spelling Bee

Centerville seventh grader wins Wright State University Regional Spelling Bee, advances to 2026 Scripps National Spelling Bee  Three Wright State students win full year of tuition during Horizon League Championship game

Three Wright State students win full year of tuition during Horizon League Championship game  Walking through open doors

Walking through open doors  Adventures await

Adventures await  Wright State to expand nursing facilities to meet workforce needs and prepare more graduates for in-demand careers

Wright State to expand nursing facilities to meet workforce needs and prepare more graduates for in-demand careers