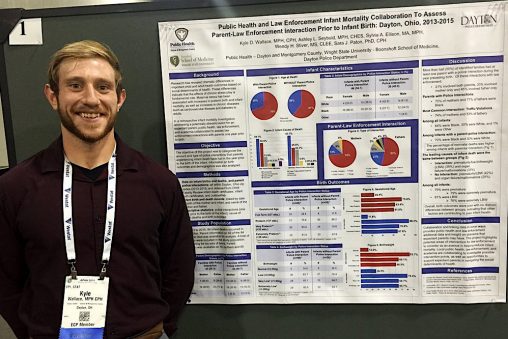

Kyle Wallace, an epidemiologist at Public Health – Dayton and Montgomery County, is a graduate of the Master of Public Health Program at the Wright State Boonshoft School of Medicine.

With the economy in Ohio preparing to reopen, new focus is being placed on contact tracing. The push is to keep track of people who have come into contact with those who have contracted coronavirus and to minimize the spread. Alumni of the Wright State University Master of Public Health Program are busy at work.

Chris Cook ’07 is health commissioner for Madison County. Kyle Wallace ’16 is an epidemiologist at Public Health – Dayton and Montgomery County. Both are graduates of the Master of Public Health Program at the Wright State University Boonshoft School of Medicine.

“As a whole, contact tracing was a little more extensive and complex when the COVID-19 pandemic began. Before the stay-at-home order, people were out and about living what was a fairly normal life,” Cook said. “That means lots of interactions with people and thus lots of contacts to trace.”

If tracing reveals that a contact also has symptoms of the sickness, then they become a probable case. Then, the process begins to trace all of their contacts. If the effort crosses county lines, the task becomes more complex, as their local health department takes over tracing.

Contacts who have symptoms of COVID-19 are isolated. Symptomatic people are isolated for a minimum of two weeks and at least one week after symptoms resolve. Ideally, there will be two negative COVID-19 tests spaced at least 24 hours apart to release someone from isolation.

Isolation at home typically means that people stay in a single room and have a bathroom dedicated to just the sick person and no one else in the family. If people are not symptomatic, they quarantine at home for two weeks. During this two-week period, their contacts monitor themselves for symptoms.

Cook’s office has completed more than 300 contact tracing efforts for COVID-19 patients. It’s likely that contact tracing for coronavirus will continue for years.

“As limitations on movement are loosened over the coming months, we will continue to see flare-ups and cluster outbreaks requiring contact tracing, which will result in isolation and quarantine of individuals and groups,” Cook said. “I think the challenge is balancing this new normal with all of the other things that are asked of public health.”

Both Cook and Wallace are hopeful that there will be renewed focus on public health efforts in the future. Perhaps there may be more funding and resources after the pandemic is over.

“Before this, a lot of people didn’t really understand public health and now they do,” Wallace said. “I think our policymakers will have to consider public health. We have been short on a lot of resources and had to scrap for certain things because of the situation and a lack of funding so hopefully we all learn from this.”

More resources directed to public health could help support the tools that are needed to properly do contact tracing. Many health departments rely on integrated tools equipped for the level and extent of contact tracing needed during this time. But some health departments don’t have access to those tools.

There are more than 3,000 local public health departments in the United States. Local health departments are notorious for using fractured data collections systems. Many still rely on forms of paper data collection.

“We’ve never had adequate and reliable funding and time to build systems that are required for this type of sustained response to a pandemic,” Cook said. “The complexity for local health departments is even deeper with many people working remotely.”

Wright State’s Industrial and Human Factors Engineering program named one of top online graduate programs by U.S. News

Wright State’s Industrial and Human Factors Engineering program named one of top online graduate programs by U.S. News  Student-run ReyRey Café celebrates decade of entrepreneurship at Wright State

Student-run ReyRey Café celebrates decade of entrepreneurship at Wright State  Wright State faculty member Damaris Serrano wins Panamanian literary award

Wright State faculty member Damaris Serrano wins Panamanian literary award  Wright State grad Hannah Beachler earns Oscar nomination for production design on ‘Sinners’

Wright State grad Hannah Beachler earns Oscar nomination for production design on ‘Sinners’  Wright State alum Emily Romigh builds on a family legacy in education

Wright State alum Emily Romigh builds on a family legacy in education