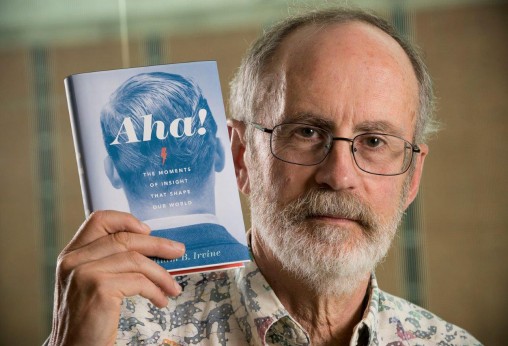

Latest book by Wright State philosophy professor William Irvine examines moments of insight that shape the world. (Photos by Will Jones)

Albert Einstein had one during a chat with a friend. Composer Gustav Mahler had one when the oars of his boat touched the water on a lake. Nobel Prize-winning physicist Richard Feynman had one when he was walking the beach.

These history-making figures all had so-called “aha moments,” sudden lightning bolts of insight that led to great ideas.

Wright State University philosophy professor William Irvine has chronicled and analyzed those aha moments in his new book, “Aha! The Moments of Insight that Shape Our World.”

“When you have these aha moments, it’s like being at a magic show,” said Irvine. “You’ve got a front-row seat and you yourself are the magician, astonishing yourself by pulling rabbits out of a hat. We all have these moments.”

Irvine says aha moments can take the form of religious insights (“the most dramatic of which is when God talks to you”), moral insights or scientific and artistic insights.

“You have to work consciously and very hard for an aha moment to come,” he said. “That’s the only way you can get your unconscious mind involved. And when the aha moment comes, that’s where it’s coming from, your unconscious mind.”

The aha moments experienced by artists are usually less dramatic than those experienced by mathematicians and scientists. As a result of having these moments, painters will change their plan for a painting and writers will alter the structure of their work.

Some of the biggest aha moments occur when the person is doing or thinking about something else entirely.

“It’s when you quit working, that the real work begins,” Irvine said. “One theory about how this happens is that your conscious mind is rule-bound, but your unconscious mind doesn’t play by the rules, so it has no problem coming up with radical ideas.”

Aha moments can’t be forced. There isn’t some trick you can do to trigger them. But devote enough conscious effort to solving a problem and you might, if you are lucky, be rewarded with an aha moment.

Sometimes, you don’t even realize you’ve had an aha moment.

Mathematical physicist Roger Penrose, who did some of the work that supported the existence of black holes in outer space, was walking across the street in London with a companion.

“Halfway across the street Penrose suddenly felt happy,” said Irvine. “When he thought about that moment later in the day, it dawned on him that he had the insight that he needed to prove the theorem he was trying to prove — except that he wasn’t quite sure what the insight was. It took a few hours of effort for him to figure it out.”

William Irvine considers himself a 21st century Stoic who tries to avoid needless anxiety, enjoy the world around him and remain optimistic in the face of setbacks.

Irvine spent much of his boyhood in Montana and Nevada, the son of an engineer who oversaw the installation of equipment in mines. He became interested in philosophy as a high school senior in Yerington, Nevada, after reading Henry David Thoreau’s “Walden” and the autobiography of British philosopher Bertrand Russell.

“I went off to college convinced that I wanted to be a philosopher — that trying to reason my way through life would be an interesting way to live,” said Irvine.

He got his bachelor’s degrees in philosophy and math from the University of Michigan and his master’s and Ph.D. in philosophy from UCLA, where he wrote his dissertation on phenomenalism, the view that physical objects exist only as perceptual phenomena or sensory stimuli.

Irvine went on to teach philosophy as an adjunct at California State University, Los Angeles; Pacific Lutheran University; the University of Cincinnati; and in 1983 at Wright State, a job that led to a tenure-track position.

“Wright State has been a good home for me,” he said. “In particular, it has been very supportive of the turn my research has taken in the last decade, away from traditional philosophical questions and toward questions that arise on the border between philosophy and other disciplines.”

Irvine has written eight books, including “On Desire: Why We Want What We Want,” “A Guide to the Good Life: The Ancient Art of Stoic Joy” and “A Slap in the Face: Why Insults Hurt — And Why They Shouldn’t.”

He is proudest of his book on the Stoics, which is still selling strong and generating reader response seven years after publication.

“All I did was introduce the ancient Stoic philosophers to a modern audience,” he said. “Stoicism tells us what in life is of greatest value and provides us with a strategy for achieving it. It also teaches us to appreciate what we’ve got.”

Irvine considers himself a 21st century Stoic. As such, his goals are to avoid needless anxiety, to enjoy the world around him and to remain optimistic in the face of setbacks.

That becomes evident in conversations with the white-bearded, 63-year-old professor, who has a twinkle in his eye and a sense of humor that often leads him to poke fun at himself. He is currently teaching courses on logic and on the philosophy of physical science.

“I have no plans to retire because I’m having too much fun,” he says.

Irvine’s book on aha moments involved extensive research.

“The book is about the role insights play in your life and more significantly the role they played in human history,” he said. “If you take human history and erase the aha moments, we would all still be living primitive lives, with no technology, no art and no religion.”

Walking through open doors

Walking through open doors  Adventures await

Adventures await  Wright State to expand nursing facilities to meet workforce needs and prepare more graduates for in-demand careers

Wright State to expand nursing facilities to meet workforce needs and prepare more graduates for in-demand careers  Wright State student-athletes make a lasting impact on local family with more to come

Wright State student-athletes make a lasting impact on local family with more to come  Wright State names Rajneesh Suri dean of Raj Soin College of Business

Wright State names Rajneesh Suri dean of Raj Soin College of Business