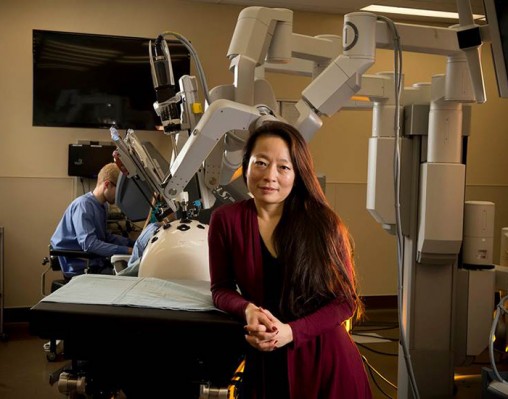

Wright State medical researcher Caroline Cao is investigating how to improve the use of surgical robotics in abdominal surgery.

Picture this: Displayed on the abdomen of a patient undergoing surgery is a live graphical image of the patient’s organs and the inserted surgical tools, enabling the surgeon to visualize and preplan the entire surgical procedure by using the body as a touchscreen.

This may soon become reality thanks to a research project headed by Caroline Cao, a Wright State University professor of biomedical, industrial and human factors engineering.

Cao has made hospital operating rooms her second home as part of the project, which is aimed at improving robotics surgery.

“Even though we are designing this to help the surgeons, we are ultimately helping the patient,” said Cao, Ph.D., the Ohio Research Scholar for the Ohio Imaging Research and Innovation Network (OIRAIN) and an expert in human factors of medical systems. “Robotic surgery is going to be the next standard of care.”

The use of robotics in surgery is growing and is most often used for abdominal, prostate and gynecological procedures. In 2012, there were an estimated 367,000 robot surgeries in the United States compared to 114,000 in 2008.

A cart next to the patient supports robotic arms that hold the surgical tools and insert them into the body. The surgeon manipulates the tools while sitting at a console and peering into microscope-like eyepieces connected to cameras that produce a stunning, magnified 3D view of the surgical site. The robotic arms enable more surgical precision.

“They get a really good sense of being there—inside the patient’s body,” Cao said. “The surgeon is still in full control, manipulating the end effectors although the contact is not direct.”

Caroline Cao is working on the robotics project with obstetrician-gynecologist physicians at Premier Health Miami Valley Hospital.

Cao obtained her doctorate at the University of Toronto and then went to Tufts University near Boston, where she was director of the human factors program as well as a faculty member of the mechanical engineering department. She won the prestigious National Science Foundation CAREER award in 2003.

It was at Tufts that Cao started the robotics research project. She is now working on the project with obstetrician-gynecologist physicians at Premier Health Miami Valley Hospital, which was the first to bring robotics surgery to the region.

Despite the advantages of robotics surgery, there is room for improvement.

It takes longer than conventional surgery and requires the time-consuming process of setting up the instrumentation and positioning the robotic arms. Surgeons must be specially trained to operate the system.

“Operating the robot is like driving a car on top of having to perform surgery,” Cao said. “It is additional work for the surgeon.”

In addition, the surgical tools can sometimes bump into each other. And the robotic system is expensive, costing about $2 million and requiring a $150,000-a-year maintenance contract.

Cao’s research involves improving the interface between the surgeons and the robotic system. And she is focusing on hysterectomies—common but difficult procedures because the surgical instruments must be positioned at a sharp angle.

“We’re working on a system that would allow the surgeon to be able to see through the patient,” Cao said. “By projecting information directly on the abdomen, the surgeon may be able to manipulate the instruments and operate by using gestures.”

The biggest challenge, Cao said, is projecting the information on a curved surface—the abdomen—with perfect alignment.

“This is going to help the surgeons perform the procedures faster, at less expense and at a high level of safety,” Cao said. “It will mean quicker healing time and lower health-care costs.”

More than 1,000 students to graduate at Wright State’s fall commencement ceremonies

More than 1,000 students to graduate at Wright State’s fall commencement ceremonies  Wright State’s Take Flight Program helps students soar high

Wright State’s Take Flight Program helps students soar high  Wright State Police Department delivers major donation to Raider Food Pantry

Wright State Police Department delivers major donation to Raider Food Pantry  Wright State engineering and computer science students earn prestigious federal SMART Scholarships

Wright State engineering and computer science students earn prestigious federal SMART Scholarships  Wright State Police Chief Kurt Holden selected for prestigious FBI National Academy program

Wright State Police Chief Kurt Holden selected for prestigious FBI National Academy program