Renee Albers, a student in the Biomedical Sciences Ph.D. Program, researches pregnancy-associated disorders.

She grew up on her family’s hog farm near the small northwestern Ohio village of St. Henry.

Today, Renee Albers is working on her doctorate in the Biomedical Sciences Ph.D. Program at Wright State University and is a key researcher in Professor Thomas L. Brown’s lab in the Department of Neuroscience, Cell Biology and Physiology. She is helping him investigate the causes of pregnancy-associated disorders that lead to premature births.

It’s a far cry from her days on the farm as the middle of five children. Albers helped her family with numerous tasks from cleaning hog crates to weaning and inoculating baby pigs to walking the fields and picking up rocks so they wouldn’t get caught in the combine.

Despite her time-consuming farm chores, she was involved in numerous activities, including 4-H for 10 years and a host of clubs, competed on the track team and even organized a ponytail-cutting fundraiser for the local cancer association.

Albers became interested in biomedical engineering her senior year after taking an anatomy class in high school and came to Wright State on an honors scholarship. Over time, she found herself drawn more to physiology than engineering and switched her major to biological sciences.

Taking an advanced laboratory techniques class stimulated her interest in possibly pursuing biomedical research.

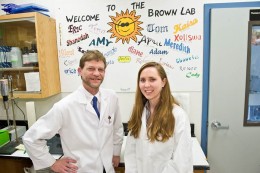

Ph.D. student Renee Albers with Thomas Brown, vice chair for research in the Department of Neuroscience, Cell Biology and Physiology.

“The difference between taking a laboratory class and working in a research lab is that you’re doing things nobody has ever done before,” Albers said. “What I find really appealing about science is that you can have very short-term goals that you can complete in steps, as well as long-term goals that may eventually help people.”

With her new-found interest in research, Albers began looking into the Wright State undergraduate research program and potential labs of interest. After discussing her ideas with a teaching assistant, she found what she was looking for in Brown’s lab and began working there as an undergraduate researcher during her junior year.

Brown suggested to her parents at the honors graduation ceremony that their daughter should consider pursuing an advanced degree. However, after getting her bachelor’s degree in biological sciences from Wright State, Albers headed back home to help on the farm and pursue agriculture commodities trading.

But after three short months, she decided she “really just needed to get back to science.” After discussing several options with Brown, she decided to apply to the master’s program in microbiology and immunology.

After completing her master’s degree, she was convinced that biomedical research was what she wanted as a career and inquired about possible Ph.D. opportunities. Although she had the choice of several outstanding programs, she chose to stay in Brown’s lab.

“Staying in Dr. Brown’s lab provided me with the opportunity to continue with our cutting-edge research that is producing findings that could really help someone someday,” she said

Brown, the vice chair for research in the Department of Neuroscience, Cell Biology and Physiology, was recently named by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to its prestigious Pregnancy and Neonatology Study Section, which is instrumental in funding national biomedical research. Three years ago, the NIH awarded Brown a five-year grant of more than $1.5 million to investigate the underlying factors that can cause preeclampsia and pregnancy-associated disorders that lead to premature birth.

“Right now, we’re doing some very interesting research,” Albers said.

Currently, Albers is investigating a gene that affects oxygen sensing in the placenta.

“We’re trying to see if this gene being overexpressed can cause preeclampsia leading to preterm birth,” she said, “and we have some very encouraging supporting data.”

About 12.7 percent of all babies born in the United States are preterm, according to the March of Dimes. The rate has increased 36 percent in the past 25 years, partly because of a rise in elective caesarean sections, an increase in older mothers and the growing use of assisted reproduction, which increases the risk of multiple births.

Premature babies can face extensive hospitalization, breathing problems because of underdeveloped lungs, undeveloped organs and greater risk of life-threatening infections, as well as an increased possibility of long-term complications. The conditions that lead up to premature births also pose serious health risks to the mother, causing high blood pressure and potential kidney damage or failure.

“Albers has the passion, motivation and drive to be a successful scientist, with a future at a research institute, pharmaceutical company or in academia,” Brown said. “I know that coming in at 2 a.m. and staying up all night to do experiments can be rough, but that is the kind of effort that she is willing to put in.”

“Renee just has that extra something that tells you that she’s going to be successful wherever she goes,” Brown added. “She’s going to do extremely well. … No doubt about it.”

Wright State University Foundation awards 11 Students First Fund projects

Wright State University Foundation awards 11 Students First Fund projects  Gov. DeWine reappoints Board Treasurer Beth Ferris and names student Ella Vaught to Wright State Board of Trustees

Gov. DeWine reappoints Board Treasurer Beth Ferris and names student Ella Vaught to Wright State Board of Trustees  Joe Gruenberg’s 40-Year support for Wright State celebrated with Honorary Alumnus Award

Joe Gruenberg’s 40-Year support for Wright State celebrated with Honorary Alumnus Award  Wright State’s elementary education program earns A+ rating for math teacher training

Wright State’s elementary education program earns A+ rating for math teacher training  Wright State’s Calamityville hosts its largest joint medical training operation

Wright State’s Calamityville hosts its largest joint medical training operation