The biology lab was in the upstairs bedroom of an old farmhouse. The chemistry department claimed the kitchen because it needed access to water and the large sink.

Such was the state of affairs during the birth of Wright State University nearly 50 years ago. Wright State has since grown to become a shining star among Ohio universities, boasting two campuses totaling 730 acres and populated with more than 60 buildings.

Its most recent additions are a spectacular Neuroscience Engineering Collaboration Building and the Student Success Center, which features a pioneering architectural design. And the Creative Arts Building is undergoing extensive renovation.

Karen Seiger, director of business development and marketing at Colibri Solutions in New York City, attended Wright State in the 1980s, graduating with a bachelor’s degree in political science in 1988.

As a student, Seiger spent much of her time at the library and writing lab as well as on the Quad and at the swimming pool. She returned to Wright State for a visit in February, the first time she had seen the campus in 17 years.

“My first impression was, ‘Where am I?’” she said. “I seriously couldn’t figure out where anything was anymore because of all of the new and updated buildings.”

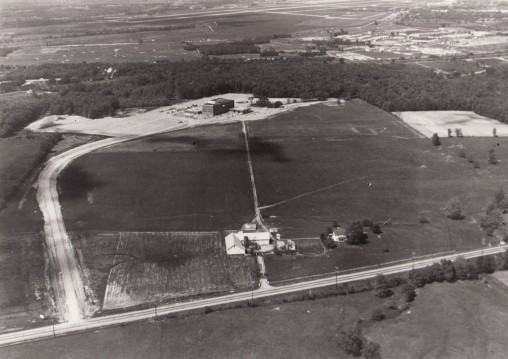

Aerial view of Wright State’s Dayton Campus, showing Airway Road and the Warner farm, foreground, the “Dayton Campus” sign, lower left, Allyn Hall, top center, and a portion of Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, upper right. (Photo courtesy of Wright State Archives and Special Collections)

The seeds for Wright State were planted in a pasture 12 miles northeast of downtown Dayton in the early 1960s. The chosen site had plenty of room for expansion, highway access and was close to Wright-Patterson Air Force Base — a dream come true for Air Force planners thirsting for a nearby university.

Founders Novice Fawcett and Stanley Allyn pressed for large acreage, saying there was no such thing as a university with too much land. So a man by the name of Henry Bader went from farm parcel to farm parcel, buying a total of 428 acres for $756,000.

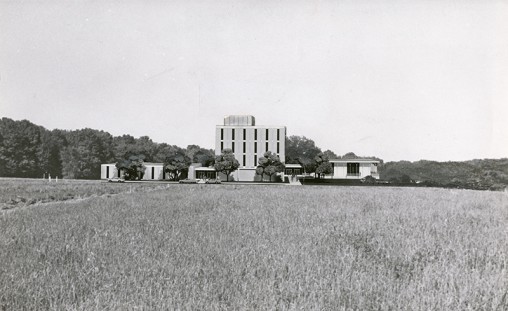

Allyn Hall, the first campus building, opened for classes in 1964. The four-story structure housed classrooms, laboratories, administrative offices, a library, a bookstore, a lounge and a vending machine room. There was one parking lot.

The last few construction dollars were used to build a bell tower, which would become a visual symbol of the university.

In 1965, ground was broken for the science and engineering building, which would become Oelman Hall and for the classroom-library building, which would become Millett. Two years later, Fawcett Hall and a university center was completed.

Completed in 1973 was Dunbar Library, a giant triangle resting on large pylons with a glass façade, a skylight roof and an atrium with an overlooking-balcony effect.

By the end of the 1970s, the university had 13 major buildings, including ones for the creative arts, medical and biological sciences, physical education and student activities, as well as a dormitory and school of medicine.

Allyn Hall before it open its doors in September 1964. (Photo courtesy of Wright State Archives and Special Collections)

Rike Hall for the College of Business was completed in 1981, the Russ Engineering Center in the early 1990s and University Hall for administration offices a decade later.

Many of the campus buildings are more utilitarian than stylish. They are referred to by some as “background” buildings because they don’t really make an architectural statement.

“But it’s really fun now,” said Wright State Architect Robert Thompson. “We can do things that stick out a little bit, but still fit on campus. The administration is open to good ideas. They are not afraid to explore some things.”

The Neuroscience Engineering Collaboration Building will bring together scientists, engineers and clinicians to create a unique synergy between biomedical research and engineering. (Photo by Will Jones)

Thompson’s office, where blueprints are stacked like pancakes on his desk, gives him an up-close look at the front porch of the campus.

“There has been a bit of a building blitz lately,” he said.

The new Neuroscience Engineering Collaboration Building, or NEC, gives the campus a splash of color.

The four-story, L-shaped structure features two wings that flank a central atrium. The building is honeycombed with laboratories and includes offices, conference rooms and a 105-seat auditorium for research symposiums.

“It is one impressive building,” said Robert Fyffe, vice president for research and dean of the Graduate School. “The work that goes on in this building will truly be cutting-edge, maybe even science fiction in its nature.”

The building is the first of its kind to be intentionally designed to drive research interaction across disciplines, bringing 30 researchers from seven disciplines under one roof to understand brain, spinal cord and nerve disorders and develop treatments and devices.

Architectural features include chilled ceiling beams that provide a natural, energy-efficient convection air current, an anti-vibration floor that preserves the clarity of sensitive lasers and microscopes and a dust-free sensors lab that is free of the tiniest speck.

About 70 percent of the building’s façade is glass, enabling natural light to stream into the structure and create an airy work environment. The façade is clad with hundreds of colorful glass “fins” that provide shading and reduce heat buildup on sunny days. In the atrium is a dazzling art installation with 3-D asterisks that mimic the firing of the brain’s neurons.

Wright State’s new Student Success Center features high-tech, active-learning classrooms, writing and math support labs and an outdoor rain garden. (Photo by Will Jones)

The new Student Success Center has a lively, unconventional shape.

The three-story, 60,000-square-foot building features a 220-seat lecture hall and large active-learning classrooms loaded with screens, laptops and other cutting-edge technology. A math center and student support services are also housed in the building.

“The whole design is unique,” Thompson said. “It was very intentional in recognizing that education doesn’t always happen in a classroom. The way the circulation spaces were designed was to create pockets where people can get together and talk. A lot of learning happens in those informal settings.”

Seiger, who has experienced the campus in both the past and present, says she is excited about the university’s future.

“Wright State is truly unique in the way it has adjusted to the times and how it has led the way in teaching students how to seek knowledge so they can think about, analyze and solve the world’s problems, large and small,” she said.

Pioneering Wright State nursing graduate promotes cancer screenings among students

Pioneering Wright State nursing graduate promotes cancer screenings among students  Wright State University Foundation welcomes three new trustees

Wright State University Foundation welcomes three new trustees  Jason Massengill named to joint role supporting military and veterans affairs at Wright State’s Boonshoft School of Medicine and Premier Health

Jason Massengill named to joint role supporting military and veterans affairs at Wright State’s Boonshoft School of Medicine and Premier Health  From reluctant student to community leader

From reluctant student to community leader  Fall funhouse

Fall funhouse