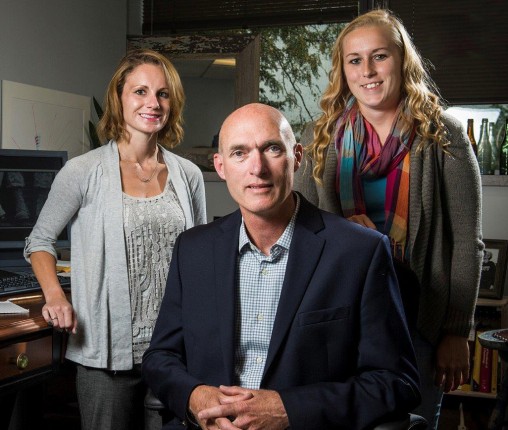

From left: Graduate assistant Nichole Kuck, associate professor Jeffrey Cigrang and graduate assistant Ashley Evans are studying whether they can develop an early detection system for problems in military marriages and help prevent bad outcomes. (Photo by Erin Pence)

Getting married young, long separations, high job stress. It’s no wonder that many military marriages go off the rails. And the pressures that fracture these relationships sometimes lead to alcohol abuse, domestic violence and even suicide.

A team of Wright State University psychology researchers has launched a project designed to develop an early detection system for problems in military marriages and help prevent bad outcomes.

Funded by an $878,000 grant from the Department of Defense Psychological Health Research Program, the study is led by Jeffrey Cigrang, associate professor in the School of Professional Psychology, in partnership with James Cordova at Clark University, the author of the “Marriage Checkup.”

They are working with Air Force psychologists to see if marriage checkups — taking the pulse of couples’ relationships — are the answer.

“The widespread use of regular dental health checkups began inside the military when it became obvious that the best way to maintain dental health was prevention rather than waiting until major repairs were needed,” Cigrang said. “We’d like to see if we can accomplish the relationship health equivalent of a dental checkup.”

Cigrang and Cordova conducted a pilot study that adapted the marriage checkup for use in military primary care clinics. Twenty couples showed significant improvement in relationship satisfaction.

Marriage checkups for the military involve three 30-minute appointments with a behavioral health provider in primary care. The brief intervention assesses the couple’s relationship history, strengths and concerns and gives individualized feedback to the couple with a list of potential helpful options.

The current research study involves recruiting about 250 Air Force couples who have been in a committed relationship for at least six months. Half will get the marriage checkup at military primary care clinics right away; the other half will serve as the control group, being monitored for six months before getting the checkup.

Cigrang said that both military and civilian marriages suffer from a low use of marriage counseling.

“It is not unusual to see couples who delay seeking help despite having experienced severe relationship deterioration, including domestic violence, which hurts both the couples, the children and the community,” he said. “We are evaluating a less threatening option for couples to seek help early.”

Graduate assistant Ashley Evans, who is working with Cigrang on the research, said it will be interesting to see the outcome of the study and likely will be the basis of her dissertation.

“I think it is something that needs attention,” she said of military marriages. “They come to therapy when it’s already broken and want you to fix it.”

After getting his doctorate in psychology at Memphis State, Cigrang worked for 24 years as a clinical psychologist in the Air Force. He retired in 2014 and joined the faculty at Wright State.

During his Air Force career, Cigrang was deployed four times, including two deployments to Iraq. During his second Iraq deployment, he led a team of 24 psychologists, psychiatrists, social workers and mental health technicians in providing mental health services to U.S. service members in southern Iraq.

“It was an incredible privilege to have a role in supporting our military men and women who were deployed to a war zone in service of their country.” he said.

Cigrang says a significant proportion of military members who kill themselves do so after experiencing some relationship loss or a relationship crisis.

“And there is growing evidence that relationship stress during deployment detracts a service member from their military mission,” he said. “In that way it affects readiness.”

Cigrang has seen deployed service members who paint the following picture: “They present with, ‘My partner is seeing someone else. My partner is expressing some doubts about whether our relationship will continue. I’m here in Iraq. My world is coming apart, but I’m here for another six months and I can’t do anything about it.’”

Cigrang is working as a principle investigator along with graduate assistant Nichole Kuck in a second, similar research project. They have applied for additional research funding.

“What I really value is being able to get research funding that supports graduate research assistants,” said Cigrang.

The project focuses on young couples who are just transitioning into the military. They will complete base-line surveys about issues that may predict how their marriages will be doing two years later.

Things that can increase the risk level include history of depression, excess alcohol use, negativity in problem-solving, argumentative natures, cohabitation before marriage and negative family history.

Screeners would then tell the couples what their risk level is and give them tools to reduce that risk, such has better managing alcohol use or sharpening their problem-solving skills.

Kuck grew up in Idaho and enlisted in the Air Force when she was 19. During her eight-year Air Force career, she worked as a mental health technician and was deployed to Iraq.

Kuck said military couples often marry at a younger age because the spouse gets deployed and the couple wants to stay together even though they may not have known each other long. In addition, there is the attraction of health benefits and better pay and housing for a service member who is married.

However, there is often a transient lifestyle, the added stress of caring for a baby, being apart from family and little opportunity for the non-military spouse to develop a career.

“Airmen and soldiers have to balance high work stress, long hours and then somehow manage family life,” she said.

This work was supported by the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs through the USAMRMC BAA for Extramural Medical Research under Award No. W81XWH-15-2-0025. Opinions, interpretations, conclusions and recommendations are those of the author and are not necessarily endorsed by the Department of Defense.

Nursing and Health Careers Camp at Wright State gives high school students hands-on experience

Nursing and Health Careers Camp at Wright State gives high school students hands-on experience  Wright State videographer Kris Sproles wins regional Emmy and Ohio journalism award

Wright State videographer Kris Sproles wins regional Emmy and Ohio journalism award  Wright State’s Lake Campus ranked as Ohio’s best value in higher education

Wright State’s Lake Campus ranked as Ohio’s best value in higher education  Wright State University earns Collegiate Purple Star renewal for support of military-connected students, veterans

Wright State University earns Collegiate Purple Star renewal for support of military-connected students, veterans  Five friends reunite in Wright State’s Boonshoft School of Medicine

Five friends reunite in Wright State’s Boonshoft School of Medicine