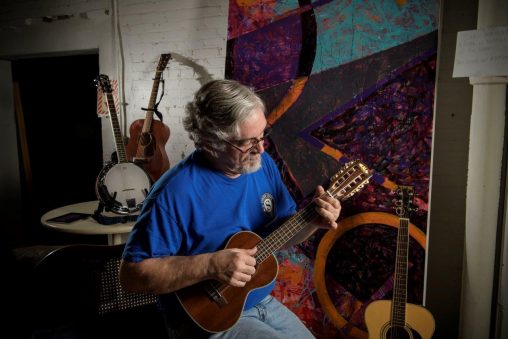

Dennis Geehan has volunteered at Habitat for Humanity, Dayton Foodbank, Project READ of Dayton and United Rehabilitation Services of Greater Dayton. (Photos by Will Jones)

Good luck finding a seat in Dennis Geehan’s car among the guitars. At any given time, there are electric, acoustical, classical and 12-string guitars, a ukulele and even a banjo stuffed with T-shirts to soften the twang.

Geehan’s guitars and volunteer work serve as his lifeline — the balm that soothes punishing nightmares from the Vietnam War, replaces a 20-year reliance on medications and gives the Wright State University alumnus his bearings after three decades of running away from the past.

“Music and volunteering create new and wonderful memories that reduce and replace my older and horrible recollections of war,” said the 64-year-old Geehan. “I wanted to choose things that make me feel good about myself because I had a lot of guilt, a lot of anger after Vietnam.”

The blue-eyed, silver-haired Geehan is the oldest of seven children in an Irish Catholic family and the son of an Air Force intelligence officer. He grew up in the Philippines, lived for a time in Alabama and then Hawaii.

After studying journalism at the University of Minnesota, Geehan enlisted in the U.S. Army in 1971, became an intelligence specialist and requested to serve in Vietnam, where he did two consecutive, one-year tours.

In the fall of 1971, Geehan suspected an imminent North Vietnamese offensive, but said his superiors dismissed it and didn’t want to hear about it. When the offensive began in the spring of 1972, Geehan’s father was suffering serious health problems at home in Dayton and was hospitalized in intensive care.

“I found my loyalties divided between the family who needed me at home and the family who need me in Vietnam,” Geehan said.

When the offensive came, Geehan witnessed the gory horror of combat firsthand. And he is still haunted by an iconic Associated Press photo of a Vietnamese girl whose clothes were burned off in a napalm attack and was running naked down a highway.

The pressures of being responsible both for his family and the soldiers in units fighting the offensive took their toll on Geehan — a toll he blames for his post-traumatic stress disorder.

“It was the guilt of allowing myself to be drawn into something like that and the anger that this could happen,” said Geehan, his voice cracking and tears welling up. “My anger was with God. My anger was with my country. My anger was with the North Vietnamese. And I was angry with myself for every American death I couldn’t prevent.”

The trauma of the war and the fact that “I was scared every day in Vietnam” led Geehan to an adrenaline jag when he returned home. He constantly pushed himself and took unnecessary risks, feeding his addiction to action.

“I was clearly living on the edge,” he recalled.

Geehan became a social-actions counselor at Fort Bragg, dealing with issues such as drug abuse, domestic violence, race relations. He left the Army in 1973, returned to Dayton in 1974 and enrolled at Wright State.

He studied chemistry, education/counseling and became a writer/sports editor on The Guardian, also working in the public affairs office at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base as a writer, photographer and editor on its newspaper, The Skywrighter.

Ultimately, he earned a bachelor’s degrees in moral philosophy and human sexuality, graduating magna cum laude in 1978. Geehan said he likely would have dropped out of college had it not been for Wright State’s Selected Studies program, which gave him the freedom to do a lot of independent study, write papers and take part in seminars and workshops. That freed him from the conventional regimentation of classes that would often trip him up.

“It created a welcoming, accepting environment for me that had enormous flexibility and allowed me to adapt their system to my needs,” he said.

After graduation, Geehan worked a few years as an educator/counselor and PR director for Planned Parenthood until he started his own printing business, helping nonprofits and political campaigns.

Geehan has worked on more than 50 political campaigns, reeling in more than one reporter with his creative publicity stunts.

As press secretary for congressional challenger Jack Schira, Geehan circulated a comic strip to local newspapers featuring “Scrappy Jack.” And he once had Schira put up his own highway billboard while catwalking 60 feet off the ground.

Geehan and Schira, both Vietnam veterans, also organized Operation Support — a volunteer effort for service members in Operation Desert Storm against Iraq in 1991 that won Geehan plaudits from then-Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney and a commendation by President George H.W. Bush “on behalf of a grateful nation.”

In the mid-1990s, Geehan was officially diagnosed with PTSD after he began falling behind in paying bills, suffering nightmares and battling bouts of confusion and fits of rage. In 2003, he gave up his printing business and moved to Seattle to get treatment, which included heavy, regular doses of prescribed medications. He returned to Dayton in 2009.

“I spent several years just watching TV, doing nothing,” he said.

In 2013, Geehan decided to get off of the medications.

“They were numbing me physically and mentally,” he said. “I couldn’t do anything. I couldn’t think. I didn’t know where my emotions were coming from. And so one day I just threw them all away and bought my first guitar in 40 years. The music replaced the drugs. Sometimes a gentle song will take me to a gentler, quieter place.”

But the demons from the Vietnam War just wouldn’t let go of Geehan. One day, he suffered a flashback, dived for cover and landed on his guitar, smashing it to pieces.

After sharing his story online, Geehan was contacted by a fellow musician who was moved by Geehan’s post and offered him a handmade classical guitar to enable him to resume his musical path to peace.

“It was such an example that I had to follow it,” Geehan said. “That’s when I decided to begin volunteering. It gave me a chance to pay something forward.”

He finds volunteer sites through the Retired Senior Volunteer Program (RSVP) of Senior Corps, a federally funded volunteer program for those over 55. He has volunteered at Habitat for Humanity, the Dayton Foodbank, Project READ of Dayton and United Rehabilitation Services of Greater Dayton.

In August, Geehan returned to Wright State to take audited courses in guitar, piano, music education and music theory. He said he hopes it will make him a better musician and a better music therapist so that he can continue volunteering and sharing his talents.

Wright State alum Lindsay Aitchison fulfills childhood space-agency dream

Wright State alum Lindsay Aitchison fulfills childhood space-agency dream  Wright State business professor, alumnus honored by regional technology organizations

Wright State business professor, alumnus honored by regional technology organizations  Wright State University Foundation awards 11 Students First Fund projects

Wright State University Foundation awards 11 Students First Fund projects  Gov. DeWine reappoints Board Treasurer Beth Ferris and names student Ella Vaught to Wright State Board of Trustees

Gov. DeWine reappoints Board Treasurer Beth Ferris and names student Ella Vaught to Wright State Board of Trustees  Joe Gruenberg’s 40-Year support for Wright State celebrated with Honorary Alumnus Award

Joe Gruenberg’s 40-Year support for Wright State celebrated with Honorary Alumnus Award