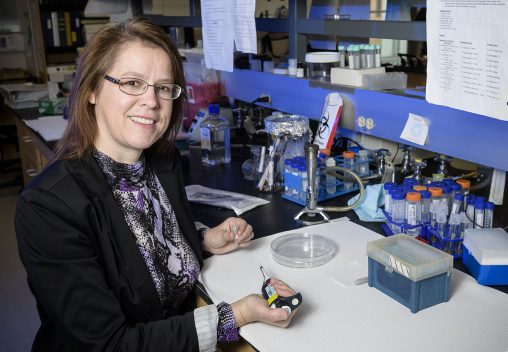

Kate Excoffon, professor of biology in the College of Science and Mathematics, received $1.8 million in funding from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases to research an anti-viral therapy to combat respiratory infections. (Photos by Erin Pence)

A team of Wright State University biology researchers is making strides on a novel approach to combatting viral respiratory infections.

The work is funded by an award from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, part of the National Institutes of Health. The project is expected to receive approximately $1.8 million over five years.

The team is led by Kate Excoffon, professor of biology in the College of Science and Mathematics.

Adenovirus infections most commonly cause illness of the respiratory system. Symptoms range from the common cold to pneumonia, as well as intestinal and serious eye infections.

Excoffon and her team have been investigating viral receptors, which must be present on human cells in order for the virus to attach to them and cause infection. The more viral receptors, the more potential for infection.

The researchers have discovered a cellular protein that interacts with the adenovirus receptor in two different ways. One part of the protein reduces the number of receptors. The other part increases them. The discovery was published in the Journal of Virology in September 2012.

“We believe we’re tapping into a natural mechanism that the body has developed and evolved over time to be able to up- and down-regulate the viral receptor,” said Excoffon. “What we’ve built are small, peptide-based molecules that can enter the cell, bind to the part of the protein that protects the receptor so more receptor is degraded and the cell is protected from viral infection.”

Excoffon envisions an anti-viral therapy that would involve the use of an inhaler, such as those used by asthma patients.

“You would take a puff and down-regulate the receptor, causing fewer receptors and prohibiting the virus from infecting cells during exposure,” she said.

From left: Timothy Williamson, Hannah Shows, Meghan Jenkins, Tom Johnson, James Readler, Jananie Rockwood, Priyanka Sharma and Kate Excoffon (in front).

The therapy may have important potential for transplant patients – people who receive new organs or stem cells, which can act as a repair system for the body by replenishing tissues.

The immune systems of transplant patients are often intentionally suppressed to prevent organ rejection. Adenovirus can be present in a patient’s body or enter with a transplanted organ, which gives the virus an opportunity to replicate and spread. If adenovirus becomes abundant in the bloodstream of children receiving stem cell transplants, for example, the death rate can be as high as 80 percent.

It is hoped that the potential inhaler therapy given early on would prevent infection by reducing the viral receptors.

The therapy could also be used by the military. Certain types of adenoviruses are endemic in the military. Currently, incoming recruits receive an adenovirus vaccination because they don’t have the antibodies to combat those virus types.

“If you swab around, you find it on boots, floors, guns and walls,” said Excoffon. “It is unclear why adenovirus types 4 and 7 are common in the military and not the general population — possibly it is because of the close living quarters or the stress they’re put under.”

The adenovirus vaccine is taken orally and if not consumed properly can trigger serious side effects. The potential inhaler therapy used before taking the oral vaccine could avert a negative response, or the therapy could possibly even replace the vaccine, said Excoffon.

The NIH award (#R01AI127816) scored in the top first percentile and the work is performed in collaboration with Stefan Niewiesk at The Ohio State University. It is focused on looking at the mechanism of the therapy, identifying other target proteins worth investigating, and how well the therapy would work in an animal model of human infection.

“We know that the treatment works in animals. We’ve done preliminary experiments in mice,” said Excoffon.

She and her team will continue collaborating with Niewiesk, who has seen promising results with the anti-virus therapy in cotton rats, which serve as a human virus infection model system.

Excoffon’s work underscores the importance of academic research.

“People underappreciate the research component of universities,” she said. “It’s well known to us that we’re drivers of innovation in ways that are unexpected. Because we will look very deeply at a particular subject, we see things and develop novel approaches, like these potential anti-virals, that few others would ever see or think about.”

Wright State University Foundation awards 11 Students First Fund projects

Wright State University Foundation awards 11 Students First Fund projects  Gov. DeWine reappoints Board Treasurer Beth Ferris and names student Ella Vaught to Wright State Board of Trustees

Gov. DeWine reappoints Board Treasurer Beth Ferris and names student Ella Vaught to Wright State Board of Trustees  Joe Gruenberg’s 40-Year support for Wright State celebrated with Honorary Alumnus Award

Joe Gruenberg’s 40-Year support for Wright State celebrated with Honorary Alumnus Award  Wright State’s elementary education program earns A+ rating for math teacher training

Wright State’s elementary education program earns A+ rating for math teacher training  Wright State’s Calamityville hosts its largest joint medical training operation

Wright State’s Calamityville hosts its largest joint medical training operation