It’s a shark tale that’s been told around the world. And a

Wright State scientist and student were right in the middle of it…

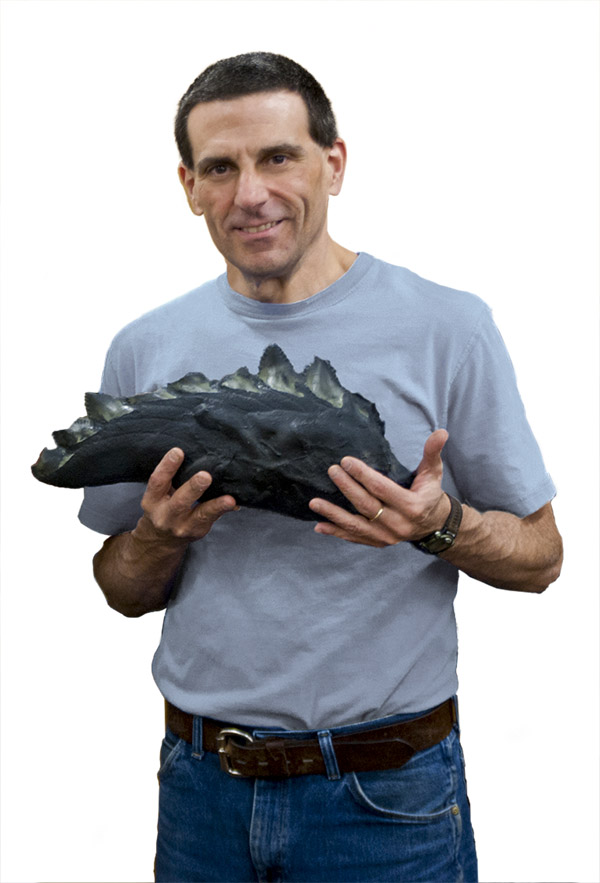

Following one of the largest finds ever made of an Edestus fossil, a jawbone from a prehistoric shark, the experts in Kentucky needed an expert of their own. They found one at Wright State University.

“I work on sharks. Especially really old sharks,” said Chuck Ciampaglio, Ph.D., researcher and associate professor of geology and paleontology at the Wright State Lake Campus.

But this shark tale doesn’t begin with Ciampaglio or even his master model-making student Mike Taylor. It begins in rural Kentucky with 25-year-old Jay Wright, holder of a sharp pickaxe and a sharper eye.

On the afternoon of February 24, Wright was 700 feet underground in Webster County Coal’s Dotiki Mine bolting a roof in the shaft.

“I noticed some flaky rocks in the roof, and a small piece of rock fell,” said Wright. “When I used a pry bar to remove some more of the rock, I caught sight of something else. Part of it was already loose. All I had to do was grab it and pull it out.”

“When I got it out I thought, gosh, what is this thing?” said Wright.

It was the jawbone of a shark that lived 300 million years ago, known to paleontologists as Edestus, a controversial species in paleontology circles for its theoretically circular orientation of its numerous and vicious teeth.

“It’s probably one of the strangest animals that ever lived,” said Ciampaglio.

Edestus’ teeth appear to have protruded from its mouth unlike any other animal known to man. After some fossils were found that show the teeth rolled up in a circular pattern, some scientists believe Edestus’ teeth rolled up into a wheel of teeth that it might have extended from its lower mouth to kill or catch prey.

“Having a wheel of teeth that goes from the inside and whirling and whirling around…the mechanics are unknown. The placement of the teeth in the mouth is unknown. It’s a really weird shark and a real interesting thing,” said Ciampaglio.

Much is unknown because shark anatomy is mostly composed of cartilage, which decays fairly fast. Bone and teeth do not.

Rarely do shark fossils give scientists such insight into the anatomy of the species because the teeth are often separate from the bone, or the fossils are too small.

Millions of years ago the western Kentucky terrain resembled a shallow ocean at times, and at others, a fresh water/salt water swamp. It’s believed that Edestus sharks would feed off of large amphibians and insects and would sometimes get trapped in the shallows.

Over time, the sharks would be entombed in layers of shale and coal. That’s why many Edestus fossils are found in western Kentucky mines, just none this big.

In this case, the jawbone is 18 inches long with teeth two inches in height and width, and unlike fossils from the species ever found before.

“This thing is big, really big for such an old shark and it has big serrated teeth. That’s something you don’t see for a shark of that age,” said Wright.

It was three months later that Wright State got the call. Experts from the University of Kentucky said Wright wanted to keep the fossil but would let them make a cast of it for study. Wright was willing to let them keep a smaller piece of bone also found with the primary fossil.

The UK scientists called Ciampaglio, one of the only paleontologists still doing research on prehistoric sharks in the region.

“I think they’re really interesting and hardly anybody is working on them anymore in the U.S. There are people from Europe that come over here to do it, but I’m really one of the only ones,” said Ciampaglio.

It just so happened that Taylor, one of Ciampaglio’s best lab technicians and an English major with 30 years of model-making experience, was available too.

The pair went to Kentucky in June. In a whirlwind, two-day visit, they made six casts in all. The models are almost identical to the genuine article.

“It was really an awesome experience examining that jawbone up close,” said Ciampaglio.

But it’s not the first time he’s been tapped for help on a high profile prehistoric shark project. Ciampaglio spends about three months a year in the field working across the country and brings students along whenever he can.

Ciampaglio is a prolific publisher on the subject and often co-authors the papers with undergraduate researchers.

Ciampaglio might be best known for his work with the National Geographic channel last year. He didn’t have to go nearly as far from home for that project.

“I did some work on megalodon—a giant prehistoric shark from about 10–15 million years ago,” said Ciampaglio. “It was as big as a Greyhound bus and we know it ate whales.”

The National Geographic channel filmed two segments with Ciampaglio in his lab at the Lake Campus for their Prehistoric Predators series.

Large predators always draw a lot of interest but Ciampaglio says this find should draw even more.

“Scientists have been postulating about this thing for over 150 years,” he said. “It was a very big predator for its time. And it was from around here.”

“We’re finally going to learn a lot more about this species because of this find,” said Ciampaglio. “It could be a real game changer.”

State grants to bolster Wright State’s electric vehicle and advanced manufacturing training for students

State grants to bolster Wright State’s electric vehicle and advanced manufacturing training for students  Wright State partners with local universities, hospitals to expand mental health care for students

Wright State partners with local universities, hospitals to expand mental health care for students  Wright State students, first responders team up for Halloween event

Wright State students, first responders team up for Halloween event  Explore Wright State Day welcomes hundreds of future Raiders

Explore Wright State Day welcomes hundreds of future Raiders  Four Wright State nursing programs receive accreditations, including new doctorate degree

Four Wright State nursing programs receive accreditations, including new doctorate degree