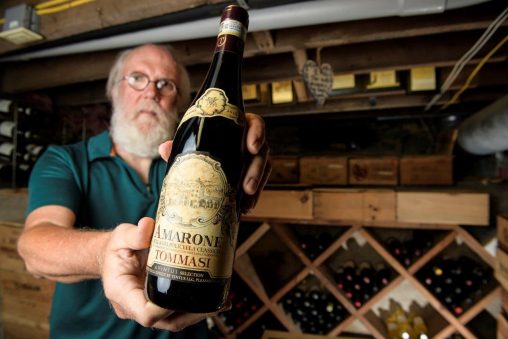

He slips it slowly and gingerly out of the cellar wine rack — a dust-furred bottle of Port nearly 40 years old. Among his thousand bottles of wine, this is perhaps Charles Taylor’s most treasured.

The retired dean of Wright State University’s College of Liberal Arts takes great comfort in his Ports, Bordeaux, Riojas and other fine European wines as he eases into the retirement years. But he is also tapping into his vast knowledge of wine and philosophy to do some work — producing stories for The World of Fine Wine, a prestigious journal published in England.

“If you would have asked me when I retired if I expected to be writing, I’m pretty sure I would have said, ‘No,’” said Taylor. “It just sort of came out. After I got started, I found I really enjoyed doing it.”

The quarterly journal, considered by some to be The New Yorker for fine wine, has published two of Taylor’s stories, is considering a third, and Taylor is working on a fourth. His articles look at wine through the prism of philosophical thought.

“Typically, in each piece what I’m doing is reading a specific essay or part of an essay that one of these philosophers has written,” he said. “And I work my way through that very carefully and slowly. Then I start writing my story.”

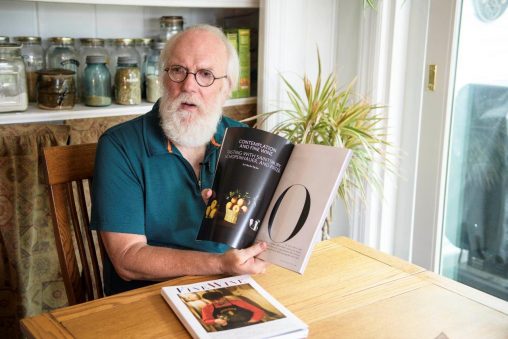

Since retiring as dean of the College of Liberal Arts, Charles Taylor has contributed articles on wine and philosophy for The World of Fine Wine journal. (Photos by Erin Pence)

Taylor’s published articles include “Contemplation and Fine Wine: Tasting with Saintsbury, Schopenhauer and Pater”; and “Expect the Unexpected: Heraclitus, Kant and the Aesthetics of Fine Wine.”

His articles are also filled with personal anecdotes and strolls through the history of wine.

In the late 1980s, while he was at Wright State, Taylor published an academic essay on wine and philosophy in the Journal of Speculative Philosophy. It was an attempt to disprove Kant’s view that while wine can give pleasure, it cannot be beautiful like a painting.

Writing for the wine journal is different, not pushing an argument.

“I realized that what I actually wanted to do in my writing was explore stuff I didn’t understand, the questions that I have,” he said. “Then I sort of turn to these philosophers. Maybe they can tell us something about this question.”

Taylor wants to give readers something to think about.

“I hope it increases and complicates their fascination with wine,” he said. “I’m trying to share that fascination with them.”

Taylor is a connoisseur with a sensitive palette that can discern the nuances of wine. He is also a self-educated wine expert, fashioned by decades of reading and research.

On this day, the 68-year-old Taylor is talking wine at his kitchen table. He’s in bluejeans, a teal-colored shirt and is shoeless. His spectacles are framed by silky white hair and a thick white beard. He talks slowly and in a thoughtful way, measuring each word.

Taylor and his wife live in a handsomely furnished house on three acres in rural Greene County. They grow vegetables in a raised-bed garden and pick heirloom apples, cherries, pears, peaches and plums from a grove of fruit trees.

The property also features one of the largest residential solar systems in Ohio, with 54 solar panels supplying power. The house, built in 1904, is heated geothermally.

Downstairs in the cellar is Taylor’s wine cache. The temperature hovers around 55 degrees. Much of the wine sleeps in stacks of blond wooden crates, which protect against moisture.

Taylor organizes the wines by region and age, with the older wines slowly making their way to the top of the racks. Hanging from a rafter is a small ceramic mobile inscribed in archaic Spanish with the words, “Wine kills slowly, and I’m not in a hurry.”

Taylor grew up in Shadyside, a village in eastern Ohio along the Ohio River that is perhaps best known for a flash flood in 1990 that left 26 people dead and destroyed or damaged many homes and buildings. Taylor spent much of his boyhood helping his uncles on their dairy farm.

Charles Taylor spent 35 years on the Wright State faculty and served as dean of the College of Liberal Arts from 2005 to his retirement in 2012.

After graduating from Shadyside High School in 1966, he enrolled at Marietta College and declared chemistry as his major. But a turning point in his life occurred when he studied abroad for a year in Vienna, Austria, where he developed a passion for art and music.

“It was the most important thing in my life, certainly up to that point,” said Taylor. “I’m suddenly immersed in this world that I really had no idea about. It was so exciting.”

Taylor frequented nearby art museums. He would go to the opera, paying $1 to stand in the back row for three hours. At an international ballet festival, he saw ballet companies from Leningrad, London and Amsterdam perform.

Taylor returned to Marietta College and graduated in 1970 with a degree in what today would be called liberal studies — blending political science, history and philosophy. He went on to Boston College to study philosophy. He lived in Brussels as an independent student and wrote his dissertation on Friedrich Nietzsche, a German philosopher whose writings on truth, morality and the meaning of existence have had an enormous influence on Western philosophy and intellectual history.

After getting his Ph.D. in 1974, Taylor took jobs teaching philosophy at Creighton University and then at Southern Oregon State College. He joined the faculty at Wright State in 1977, was named dean of the College of Liberal Arts in 2005 and retired in 2012 after a 35-year Wright State career.

Taylor’s love affair with wine began when he was a student in Vienna, where he would sample Austrian wines in basement weinkellers. His interest intensified as a graduate student in Boston and Brussels and in California, where he worked in the tasting rooms of two small wineries. In the early 1970s, he began collecting wines.

Nearly all of Taylor’s wines are reds from Europe. He likes them because they improve so much with age, unlike many domestic wines. He has paid as much as $200 a bottle.

“Very early on I realized that if I wanted to enjoy wine at its best point, I needed to put it in the basement and leave it alone,” he said. “I can now go downstairs whenever I want and get a 20- or 30-year-old bottle of wine.”

Walking through open doors

Walking through open doors  Adventures await

Adventures await  Wright State to expand nursing facilities to meet workforce needs and prepare more graduates for in-demand careers

Wright State to expand nursing facilities to meet workforce needs and prepare more graduates for in-demand careers  Wright State student-athletes make a lasting impact on local family with more to come

Wright State student-athletes make a lasting impact on local family with more to come  Wright State names Rajneesh Suri dean of Raj Soin College of Business

Wright State names Rajneesh Suri dean of Raj Soin College of Business