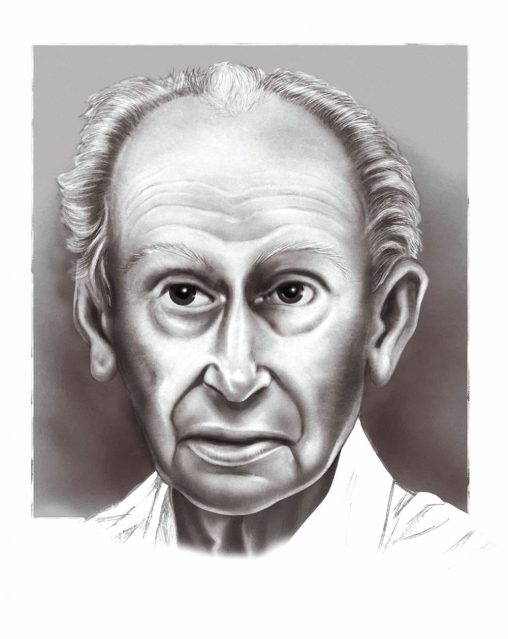

Samuel Heider told his story of surviving the Holocaust in the book “Miracle of Miracles.” (Illustration by Randy Palmer)

He survived five Nazi concentration and death camps, lost all of his immediate family to the gas chambers, and came face to face with Josef Mengele, the German physician known as the “Angel of Death” for his cruel experiments on prisoners. Despite his harrowing history and near-death experiences, 95-year-old Samuel Heider had never written a book—until he met Stevie Kremer ’72, an alumna and former adjunct instructor.

The seeds of the book “Miracle of Miracles” were planted in 2017 when Heider spoke at Wright State and Kremer overheard him say he had always wanted to write a book.

That led to Kremer volunteering her services to put his story on paper, conducting numerous interviews with Heider and two years of research.

“I found him to be such a charming and interesting man, and he seemed to like me,” said Kremer. “I told him of my writing and editing experience and assured him that I could tell his story from his point of view and without embellishments.”

Twice a month, Kremer would drive from her home in Centerville to Heider’s home in northwest Dayton to have breakfast and talk. Kremer went online to access Heider’s lectures and contacted librarians at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C., and at the University of Southern California’s Shoah Foundation.

Slowly, Heider’s story began to take shape in book form.

He was born Szmul Josef Hajder on April 5, 1924, in the Polish village of Biejkow, the third of six children. In October 1941, the family was forced by the occupying Germans to leave their fruit farm and move into a ghetto in Bialobrzegi, Poland.

Heider was separated from his family at 17 and sent to the Radom Ghetto in central Poland. He later learned that all of the members of his immediate family had been killed at the Treblinka concentration camp.

In the summer of 1944, with the Russian army advancing in Poland, Heider was moved to the Auschwitz concentration camp in southern Poland. There he faced Mengele, who with a flick of his wrist indicated who would live and who would die.

Heider was later moved to the Vaihingen, Hessental, and Dachau concentration camps in Germany. On April 30, 1945, he was liberated by American soldiers, who found him weighing only 74 pounds and battling typhus.

“His physical strength and religion probably were the things that pulled him through,” said Kremer. “He would talk about his close calls with death. He would talk about being grateful to all of the people who saved him. That’s where the title came from—’Miracle of Miracles.’”

Stevie Kremer ’72, alumna and former adjunct instructor, helped Heider tell his story of surviving the Holocaust in “Miracle of Miracles.”

After living several years in a displaced-persons camp, Heider immigrated to the U.S. in 1949. He came to Dayton, where he made sausage, worked at a clothing company, and founded a scrap metal business.

Heider passed away Nov. 21, 2019. Three days later, his friends and relatives braved icy winds to file into the chapel at the Beth Jacob Cemetery in Dayton. With standing room only, mourners crowded in to honor the 95-year-old.

After his son, one of his daughters, and a rabbi spoke, the mourners quietly followed the pallbearers outside to the gravesite, where officials offered prayers and Heider was laid to rest beside his beloved wife, Phyllis, also a Holocaust survivor.

“When his coffin was lowered and his family and friends symbolically placed shovelfuls of earth into the grave, I turned to leave, tears stinging my eyes in the frigid air,” said Kremer. “I lost a friend, but the world lost an important voice and eyewitness.”

Kremer wonders whether Heider had been waiting until his story was published and he was certain it would survive him.

“We will never know,” she said. “However, I am thankful that I had the honor to be his friend and help write his story, a valuable one that he knew had to be preserved.”

Kremer has a long history with Wright State.

When she began studies in the fall of 1968, there were only four buildings on campus. As a student, she worked as a tutor in biology, English, and German, bound books in the tunnels, and worked 12-hour shifts taking student and faculty ID photos. She earned enough money to study one summer at University College in Dublin, Ireland, where she earned a certificate in Irish culture.

Kremer helped write the proposal to establish the summer Wright Start Program for high school students and taught English in the program for three summers.

Not fond of math, she changed her major from pre-med to English with a minor in German. She earned her bachelor’s degree in 1972 and qualified for membership in Phi Eta Tau, the Wright State honor society.

Kremer pursued her master’s degree in English at Indiana University, where she was elected president of international students in graduate housing.

“I found myself hosting journalists from behind the Iron Curtain, newspeople brought to the U.S. by the Department of State to help dispel propaganda,” she recalled. “I helped organize various language tables in the dorm cafeteria so students could practice their foreign languages with native speakers, foreign movie nights, and international dinners.”

Samuel Heider holds his identification certificate from Landsberg Displaced Persons Camp in Germany, where he lived from 1945 to 1949. (Photo credit: Marshall Weiss, The Dayton Jewish Observer)

After graduation, she returned home to Centerville, taught grammar and composition, and worked as a reporter, photographer, and drama critic at the Beavercreek Daily News.

In 1976, she married and moved to Fort Nelson, British Columbia, where she taught basic job readiness training and GED courses to the native Canadian Slavey Indians, as well as English as a second language to immigrants.

In 1982, Kremer, her husband, and their young daughter returned to Centerville. Kremer got a job as a senior technical writer and editor at the University of Dayton Research Institute, was a substitute teacher, and taught evening classes.

The opportunity to tell Heider’s story came in 2017.

Kremer said she designed “Miracle of Miracles” to be used as a teaching tool to educate students about the Holocaust. She included photos, a map, and a glossary of Jewish terms so readers of all faiths would understand what they mean.

To purchase “Miracle of Miracles,” email author Stevie Kremer at sakremer.writer@gmail.com.

This article was originally published in the spring 2020 issue of the Wright State Magazine. Find more stories at wright.edu/alumnimag.

Wright State to expand nursing facilities to meet workforce needs and prepare more graduates for in-demand careers

Wright State to expand nursing facilities to meet workforce needs and prepare more graduates for in-demand careers  Wright State student-athletes make a lasting impact on local family with more to come

Wright State student-athletes make a lasting impact on local family with more to come  Wright State names Rajneesh Suri dean of Raj Soin College of Business

Wright State names Rajneesh Suri dean of Raj Soin College of Business  ‘Only in New York,’ born at Wright State

‘Only in New York,’ born at Wright State  Wright State president, Horizon League leaders welcome new commissioner

Wright State president, Horizon League leaders welcome new commissioner