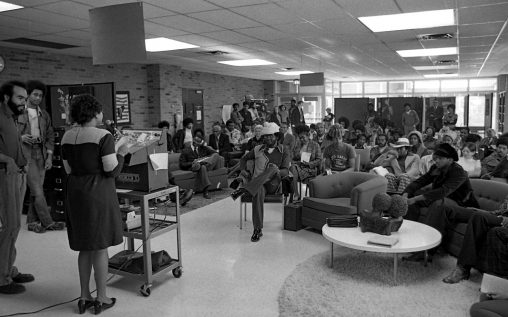

Yvonne Chappelle Seon, director of the Bolinga Center from 1971 to 1973, addresses students, faculty, and staff in the Bolinga Center in 1973. (Photos courtesy of Wright State University Special Collections and Archives)

The Bolinga Black Cultural Resources Center celebrates its 50th birthday this year. The cultural impetus for its founding, however, can be traced back to the very first days of Wright State’s existence. Its role in the university’s mission has expanded over the decades—a role perhaps more critical today than ever.

When Wright State was founded in October 1967, the campus population included an estimated 25 Black students, one Black faculty member, and one Black staff member.

“When I started at Wright State in 1966, we referred to it in the African American community on campus, not as Wright State, but ‘White State.’ [There were] very few of us on campus in 1966,” said William Gillispie ’70. “So, the atmosphere was like we were totally culturally invisible. It was pretty much alien to anything that we were interested in experiencing.”

Gillespie’s wife, Linda Moody Gillispie ’73, remembers the campus climate similarly.

“I remember, I was the only Black student in most of my classes,” Moody Gillispie said.

Carolyn Wright ’73 agreed that the atmosphere on campus was difficult to navigate for Black students when she first stepped on campus in 1969.

“When I came, I remember a very sterile environment,” Wright said. “But the Black upperclassmen really took hold of us. They were very interested in navigating and helping us in terms of educating students about the contributions of Black folks in America.”

A small group of Black students came together in 1968 to form the Committee for the Advancement of Negro Education (CANE) to advocate for themselves and speak out against injustices, both across America and on campus. CANE was later renamed the Committee for the Advancement of Black Unity (CABU).

The Black students of CABU worked tirelessly between 1968 and 1970 to organize protests, rallies, and sit-ins that took place on Wright State’s campus. Similar activities were taking place at lunch counters, bus stops, voting booths, and other universities across the U.S.

These actions by Wright State’s Black students led to the 1971 organization and founding of the Bolinga Center.

CANE president Thomas White speaks to the crowd in Oelman Hall during the Martin Luther King Jr. memorial event in 1968.

Equity for all

On April 4, 1968, the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee, at the age of 39. Over 150 students attended an on-campus memorial service in Oelman Hall.

“[There were] some white folk singers, using this as a platform to use folk songs to commemorate the legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King, and I remember vividly, they were singing, ‘How many roads must a man walk down?’” said Gillispie, who attended the memorial. “Tom White [CANE chairman and student] interrupted them and said, ‘It’s been way too many roads! This is not for you. This is for us to celebrate the legacy of Dr. King.’”

Gillispie recounted that White then completely took over the memorial, speaking from a Black perspective “as opposed to having, what we considered, ‘sympathy’ from the white presenters about our loss of a leader,” he said.

White then asked the Black students in the crowd to stand up if they had experienced racism and/or injustice at Wright State. Larry Crowe ’06, a student in the crowd, stood up.

“All the Black students stood up and there was a kind of gasp in the audience,” Crowe said.

Following this event, the students who formed CABU started meeting regularly to formulate a plan to present to the university. The aims of this plan were to increase diversity on campus and create a sense of inclusivity among the campus population.

“We were not sitting idly by, waiting for an event or an incident,” Gillispie said. “We were active, we were meeting, and we were coming together to deal with many issues that were confronting us as Black students at the university.”

Together, we march on

Novelist Alex Haley visited the Bolinga Center in 1971 while he was writing “Roots: The Saga of an American Family,” considered one of the most important U.S. works of the 20th century.

CABU wanted an end to discriminatory practices in hiring and student recruitment. And, taking the lead of Black students across the nation on other college campuses, they began organizing to see these issues addressed at the university.

In May 1970, police opened fire in a dormitory on the campus of Jackson State College (now Jackson State University) in Jackson, Mississippi, killing two Black students and injuring 12. This incident occurred just 11 days after National Guardsmen shot and killed four students at Kent State University in Kent, Ohio.

Several days later, CABU held a rally to commemorate the Black students slain at Jackson State.

“After the shooting at Kent State, white students were upset about it,” said Crowe. “We were upset, too, but nobody mentioned the students killed at Jackson State. They were killed in a dorm room and troopers shot them through a window. And we wanted to talk about it, as well as a lot of other things that happened to Black folks that just got swept under the rug.”

Crowe said the students of CABU joined together to publicly discuss their grievances and present their formal list of demands to university President Brage Golding on behalf of Wright State’s Black population. After the rally, students met with Golding privately and had what they said was a heartfelt and honest discussion about the university atmosphere.

“We took this as an opportunity to come up with demands because the university seemed to want to make change after Kent State,” said Crowe.

During that discussion, students presented their idea of a Black cultural center. They envisioned it as a facility housing African American books and media, paintings, and artifacts, a place to invite guest speakers, for Black organizations to hold meetings, and for students to hold discussions. Golding agreed to most of the students’ demands, including establishing the center. Some of the other demands included an increase in the hiring of Black faculty and administrative staff and an increase in the efforts to recruit Black students.

Though the majority of their demands were met, their fight for racial equality on Wright State’s campus was not complete.

In December 1970, during the winter break, 20 Black Wright State students walked into Golding’s office suite and staged a sit-in, holding handwritten signs firmly and chanting loudly. The sit-in, which lasted over four hours, was peaceful.

They had come to protest the firing of a Black employee, Betty Thomas ’68, an alumna and an assistant director in the Office of Financial Aid. Thomas claimed she was passed over for a promotion in her department and “felt discriminated against on the basis of race and sex,” according to an article in The Guardian, the student newspaper, published in January 1971.

“I can remember going in and taking over,” said Wright. “I think the president was having a meeting in the executive suite, and we marched in like soldiers and lined the wall.”

Upon their return to campus after the start of the spring quarter, a group of Black students organized in support of Thomas again, blocking every campus entrance and exit with their vehicles early one January morning. This created a backup of cars on Colonel Glenn Highway, impeding access to Wright-Patterson Air Force Base. The Fairborn police were called, and the Dayton Daily News ran the story under the headline “Blacks Block Traffic at WSU.”

Yvonne Chappelle Seon, right, and President Brage Golding greet students and community members at the opening of the Bolinga Center on January 15, 1971.

A new light

In their list of demands presented to Golding, students asked to be part of the hiring process for the center’s director.

Wright State hired Yvonne Chappelle Seon, Ph.D., former director of student life programs at Wilberforce University. Prior to Wilberforce, she worked for Congolese Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba. Seon is the mother of award-winning comedian Dave Chappelle, who still resides locally.

Seon had a vast background in the African diaspora, the worldwide collection of communities descended from people from sub-Saharan Africa, predominantly in the Americas.

“She just brought a wealth of knowledge, especially about the African continent,” said Wright.

Also included in the list of demands presented to Golding was for the university to offer African and African American education programs and courses. Seon helped bring some of those courses to the curriculum, including a course in Négritude, a literary theory that cultivated Black consciousness across Africa.

The Bolinga Black Cultural Resources Center officially opened its doors in Millett Hall on January 15, 1971, what would have been Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s 42nd birthday.

“Bolinga” means “love” in Lingala, an African language.

At the center’s opening, Seon welcomed Ebenezer Debrah, ambassador from the African nation of Ghana. Debrah presented Wright State officials with a towering, polished wooden sculpture—which is still at Bolinga today—symbolizing the connection between Africa and America.

“From the beginning, the students really embraced it,” Wright said. “It really felt like a community.”

Shortly after its opening, the center hosted a talk by novelist Alex Haley, who was writing “Roots: The Saga of an American Family.” The bestseller is considered one of the most important U.S. works of the 20th century.

“[Seon] was the first professor that I really had that collegial relationship with, where I would go to her home and have dinner with her and her husband,” Crowe said. “I felt like part of the extended family, and a lot of students experienced that. You have to go to an Ivy League university to get that kind of attention, usually.”

Through these connections, Bolinga also hosted speakers such as poet Léon Damas; poet Sam Allen; writer Sam Greenlee; Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare under President Lyndon Johnson, John W. Gardner; and comedian Dick Gregory.

“She exposed us to a lot of information, books, culture. To me, that was one of her greatest strengths, just sharing things we didn’t know about,” said Moody Gillispie.

Through the years

In 1973, Moody Gillispie was named interim director of Bolinga until Arthur Thomas took the helm. Thomas placed an emphasis on Black America, making Bolinga a center for discussions and study of social justice issues.

He added a course titled “Contemporary Problems in Black America” to the curriculum. He also brought in speakers such as Vernon Jordan, president of the National Urban League; Ohio Congressman Louis Stokes; and journalist Tony Brown.

Throughout the 1970s, Bolinga was mentioned frequently in Jet, the magazine covering news, culture, and entertainment within the Black community.

In 1978, Wright was named director of Bolinga, and maintained Bolinga’s educational focus on African and African American history and culture.

“I knew that Bolinga represented a place, an oasis where we could continue to learn, exchange, and dialogue about the contributions of Black people, not only for Wright State, but also the Dayton community,” Wright said.

In 1980, the Bolinga Center Scholarship was created with the Wright State Foundation and has provided nearly $40,000 in scholarships to more than 65 students.

Throughout the 1980s, Bolinga continued to bring in speakers such as Ambassador B. Akporode Clark of Nigeria; activist Angela Davis; Naomi Tutu, daughter of South African human-rights activist Desmond Tutu; and Rita Dove, the first Black Poet Laureate.

“We brought in speakers from all over the country,” said Wright. “Having them in Bolinga, made it more meaningful.”

Through the Bolinga Center, Black students helped develop peer tutoring and mentoring programs, such as Peer Supportive Services Program (PSSP), which has provided tutoring and counseling for minority students to support them in their college transition. Bolinga also aided in the creation of several student groups, including the Black Student Union, Phi Beta Sigma Fraternity, Wright State’s chapter of the NAACP, and the Society of Black Engineers and Scientists.

Frank Dobson Jr. served as director of Bolinga until 1990, when Lillian Johnson was named director, providing students energy and vision on how to enact positive change in the 1990s.

In 1992, four Los Angeles police officers involved in the beating of motorist Rodney King were acquitted and the Black community around the nation was outraged. Frustration over the verdict and longstanding social issues led to protests in several major cities throughout the country, including cities across Ohio.

The King verdict brought to the forefront the injustices facing Black Americans, and the Bolinga Center provided an outlet for Black students at Wright State to engage in discourse about ongoing issues affecting the Black community. Johnson invited speakers such as Manning Marable, Ph.D., founder of the Institute for Research in African-American Studies; Marcia Gillespie, editor-in-chief of Essence Magazine; and poet Nikki Giovanni.

In 1994, Harley E. Flack, Ph.D., became the first Black president of Wright State. During his tenure, many Black students said he became a “blessing” in their lives. Flack passed away while in office in 1998.

“During his tenure, he provided more scholarship opportunities for Black students, which was wonderful to see,” Moody Gillispie said.

Leading up to the 30th anniversary of Bolinga in 2001 came the formation of the African-American Alumni Society, which has provided nearly 30 African American students with scholarships.

In 2005, Seon returned to Wright State to oversee Bolinga’s 35th anniversary celebration. She was hired full time as director again until her retirement in 2008.

No justice, no peace

In the coming year, Wright State will continue to honor and commemorate the legacy of the Bolinga Center. But as the center moves into its 50th year, many Black alumni are wondering what the future holds, considering the current state of racial injustices in this country.

“With all the issues that we’re dealing with regarding racism, I think it’s time for us to re-establish the Bolinga Center, like it was when it was created,” said Gillispie.

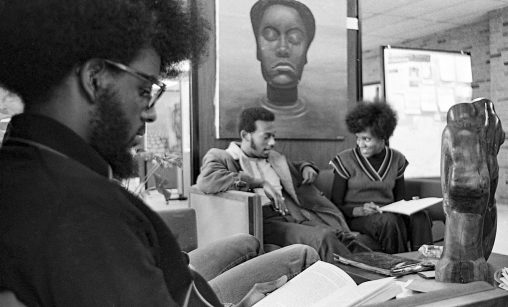

Linda Moon Gillispie, right, speaks with a fellow student while another studies in the Bolinga Center in 1973.

As protests erupted across the country and the world in response to the killing of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer this summer, current Black students have taken action. The Black Student Union (BSU) issued a joint statement with the Student Government Association (SGA) calling for racial bias training for all members of the Wright State Police Department, and for the university to organize town halls and open dialogues on racial inequality.

“We call upon all members of the Wright State campus community to look deep at themselves, to recognize implicit bias, and privilege, and be willing to make changes that will ensure our campus is a place where everyone can feel safe,” the statement said. It was signed by students Ivan Mallett, president of SGA; Dorian Buford, president of BSU; Adrian Williams, vice president of SGA; and Kevin Jones, director of inclusive excellence for SGA.

Buford and BSU also issued a separate statement to the university social media team, asking that the recurring issues of Black students be addressed on the university’s official social media channels.

“We need your voice, your support, your sponsorship, and your upliftment at this challenging moment,” the statement said.

Shortly thereafter, the university administration established the Racial Equity Task Force, and held forums on racial inequality over the summer. In 2018, student organization Black Men on the Move created the “Retain The 9” initiative to focus on the retention of Black students. Retain The 9 refers to the 9.9 percent of students on campus who are African American.

The Wright State University Foundation recently established a Retain The 9 scholarship and a memorial scholarship in the name of George Floyd.

Crowe and Gillispie said the work students are doing is inspiring.

“We were agitating for social change,” Crowe said. “And the fact that Black students are doing that now—they’re continuing in that legacy.”

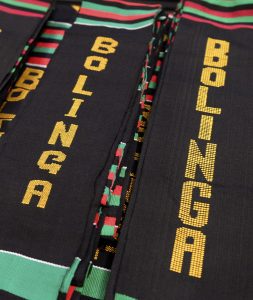

Each year, the Bolinga Center holds a ceremony to honor graduating African and African American students and presents them with a traditional Kente stole to wear during the commencement ceremony.

Wright State has battled financial difficulties since 2015, and Bolinga has been on the receiving end of several programming and staffing cuts. The last Bolinga Center director position was cut as a result of university layoffs in July 2018.

Tonya Mathis, current interim associate director of Bolinga, said the center is a major part of the university fabric. Mathis previously served as the president of the African American Alumni Society and said the society plans to celebrate the 50th anniversary formally at their Sapphire Jubilee signature event in January 2021. The theme will be “A Prelude to 50 Years.”

“The center’s presence on campus helps attract new students due to its resources and the cultural opportunities it provides students, such as leadership involvement opportunities, cultural programming, and mentoring groups,” Mathis said.

Wright said she wants to see Bolinga be given more resources in the near future. An even stronger Bolinga would help with recruiting and retaining students and provide a louder voice on social justice issues, she said.

“As we look to the future, there is a need for vigilance as it relates to higher education for Black students, and Bolinga needs to continue to play a significant role in seeing that need is fulfilled,” she said. “The Bolinga Center must play a leading role in defining and promoting the cultural as well as intellectual opportunity for young Black people.”

For more information about the Bolinga Black Cultural Resources Center, visit wright.edu/bolinga.

This article was originally published in the fall 2020 issue of the Wright State Magazine. Find more stories at wright.edu/alumnimag.

A foundation of support

A foundation of support  Wake-up call

Wake-up call  Centerville seventh grader wins Wright State University Regional Spelling Bee, advances to 2026 Scripps National Spelling Bee

Centerville seventh grader wins Wright State University Regional Spelling Bee, advances to 2026 Scripps National Spelling Bee  Three Wright State students win full year of tuition during Horizon League Championship game

Three Wright State students win full year of tuition during Horizon League Championship game  Walking through open doors

Walking through open doors