“It’s a good idea to support something that’s worthwhile. Decent teaching in the schools is worthwhile. We need good teachers in schools, and this is a way for it to be done… I want Wright State to prosper,” said Cynthia King, professor emerita of classics. (Photo by Erin Pence)

The year is 1975, and what a year it is. The leisure suit arrives on the fashion scene. Sony introduces the Betamax video recording system, giving birth to videocassette recorders—commonly called VCRs. Mood Rings and Pet Rocks are popular gifts.

Meanwhile, at still-young Wright State University, something wonderful happens. Bill and Cynthia King, both faculty members in the Department of Classics, and John Fortman, Ph.D., in chemistry, make their first donations to the university.

While many items from 1975 are in the dustbin of history, not so the goodwill of the Kings and Fortman. Each year since, they’ve donated to Wright State. That’s 45 years without interruption, making them the longest givers in Wright State’s history.

Captain and Tennille’s “Love Will Keep Us Together” is song of

the year.

When Cynthia King talks of the yearly donations in the King name, it’s evident her late husband’s spirit is with her. She begins by referring to herself in making the donations since he passed in 2017, then quickly backtracks to say “we” instead of “I.” Love persists; it shows.

The two were a team from when they met in graduate school at the University of North Carolina. A few years after they earned their Ph.D.s, the married couple relocated to Dayton to lay the groundwork for a program in the classics department at a newly forming university. In 1964, Bill became a founding faculty member of what would become Wright State; Cynthia joined him on the faculty a year later.

They established the Department of Classics, even though, according to university history, “the library, which was housed in the cafeteria, had a classics collection of only 25 books. On this foundation, the Kings built the classics program into a vital part of the campus community.”

Bill and Cynthia King speak at Wright State’s Blast from the Past event in April 2012, where Speakers shared stories of their experiences at the university.

Bill’s specialties were Greek and Latin literature, Roman art and archaeology, and scientific and medical terminology. Cynthia’s also was in Greek and Latin literature, with Greek art and archaeology and classical philosophy.

Academic life hummed along for several years. Then, as Cynthia tells it, came a campus-wide request for scholarship funds. “That was a wonderful idea,” she says. “We hopped on that as soon as it became a possibility.” Thus began the first of their annual donations.

“We wanted to support the students,” Cynthia says with a rush of resolve. “We wanted to support the teaching of Latin and to get people ready to teach Latin in high schools. The idea was to get Latin teachers prepared, and other good teachers too: English, social studies, history.”

Why Latin? “It’s important for literacy,” she says firmly. “To have some understanding of language. Doctors and ministers have their Greek and Hebrew.” Latin is important in the liberal arts. “There are still people who want to learn something besides business and data and science and video games.”

The Kings faithfully continued their annual donation, even after they retired in 2002. “We sensed the opportunity existed and we wanted to support the students,” Cynthia says.

They remained active in the Wright State community until Bill, a double amputee, experienced declining health. He passed away November 30, 2017; they had been married for 56 years at that time.

Still, Cynthia kept up with the donations in their name—to the William and Cynthia King Scholarship.

As for her most recent donation, Cynthia gives a nod to changing times. “Some goes to the library archives, and this time to the College of Liberal Arts emergency fund.” She says that fund partially grew from the pandemic to help students who run into trouble with sudden expenses, like repairing a car to get to and from classes.

The reason for her continual giving is simple. “It’s a good idea to support something that’s worthwhile. Decent teaching in the schools is worthwhile. We need good teachers in schools, and this is a way for it to be done.”

Also, “I want Wright State to prosper.”

Engineer Ed Roberts developed the Altair 8800, the first personal computer.

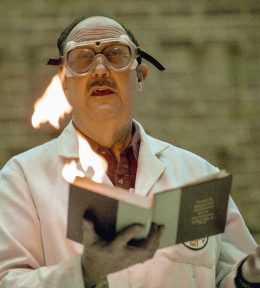

Before there was Bill Nye the Science Guy and any number of others who blended the teaching of science with entertainment, there was John Fortman. He wasn’t as effervescent or nationally known as Nye and their fellow infotainers. But Fortman, in a sense, showed them how it was done, especially in the world of chemistry.

Fortman, with his Wright State colleague Rubin Battino, Ph.D., created chemistry shows for middle and high school students and their teachers. The shows were fast-paced, lively, and, well, explosive.

“We’re working with middle and high school students, and they don’t have terrifically long attention spans,” Battino said. “So there just can be no gaps. When we work together, it’s just bang, bang, bang, bang.”

The demonstrations included spiraling towers of flame, billowing clouds of condensed water vapor, and a few sonic boom-like explosions.

Or, as Fortman said: “If you become a teacher, remember, instead of telling them, demonstrate.”

Fortman and Battino provided these educational experiences for about 35 years. Their 90-minute shows included more than 40 demonstrations, and were watched live by about 250,000 students and teachers. On many occasions, Fortman himself took to the road to showcase the wonders and excitement of chemistry to auditoriums full of students and their teachers.

All the while and behind the scenes, Fortman exhibited another kind of chemistry—between him and Wright State. In 1975, Fortman made a donation to the university to help students. Every year after that—including since 2001, when he retired as professor emeritus of chemistry after 36 years of teaching first-year students and inorganic chemistry—he has donated to the university.

One might think the genesis of the donation was purely to advance the teaching of chemistry. But there’s a deeper, more personal reason.

When Fortman was a student, the higher education choices in and around Dayton were limited. He earned his Bachelor of Science from the University of Dayton in 1961 and his Ph.D. in physical inorganic chemistry from the University of Notre Dame in 1965.

Then Sinclair Community College and Wright State came along, offering more economical tuition.

“I always kept in mind that I had the opportunity to stay at home, work part time, and go through school,” Fortman says. “I felt that I should give the opportunity to other Dayton students who couldn’t afford to go away to college. So when the opportunity came to contribute to a scholarship, it was my way of giving a little back. Wright State gives an opportunity to students who otherwise couldn’t afford to attend school.”

As the years went by, Fortman continued the donations, driven in part by the largess of chemical companies and their foundations.

“They saw the need for chemists,” he says of the large companies, “so they donated.” Fortman, for instance, said he made the initial connection with Dow Chemical Company to contribute to scholarships. “My own [continued donation] was a natural connection to these companies.”

Asked for his thoughts on the importance of faculty donating to help students, he says without hesitation that teachers need to think back to how they got their education, and the financial help they got along the way.

One more nod to 1975: the top TV show for the fifth consecutive year was “All in the Family.” Fitting that the Kings and Fortman stepped forward and continue to do so as part of the greater Wright State family.

If you would like to start your legacy of giving, visit wright.edu/giving.

This article was originally published in the spring 2022 issue of the Wright State Magazine. Find more stories at wright.edu/alumnimag.

Walking through open doors

Walking through open doors  Adventures await

Adventures await  Wright State to expand nursing facilities to meet workforce needs and prepare more graduates for in-demand careers

Wright State to expand nursing facilities to meet workforce needs and prepare more graduates for in-demand careers  Wright State student-athletes make a lasting impact on local family with more to come

Wright State student-athletes make a lasting impact on local family with more to come  Wright State names Rajneesh Suri dean of Raj Soin College of Business

Wright State names Rajneesh Suri dean of Raj Soin College of Business