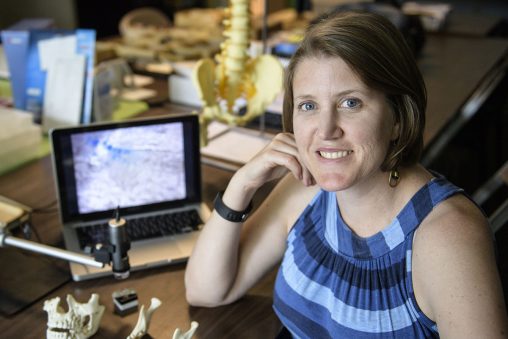

Amelia Hubbard, associate professor of anthropology, had her students devise creative ways to demonstrate their mastery of classroom lessons.

A music video on evolutionary biology and an infographic about the cultural roots of race were part of a novel approach to teaching and learning at Wright State University in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic.

During the Fall Semester, Amelia Hubbard, associate professor of anthropology, came up with a new way for her students to demonstrate their learning by allowing them creative expression instead of undergoing traditional assessments. She replaced exams with having students produce creative pieces such as videos based on what they had learned.

Hubbard still gave mini-quizzes to test basic content recall and understanding, but in her introductory and upper-level courses, students were asked to create a video of four minutes or less, a one-page infographic, a learning game or a visual art piece.

Anthropology major Anna Fox produced a catchy music video titled “Dear Theodosius” in which she sings her essay. The video is a reference to Theodosius Dobzhansky, a prominent Ukrainian-American geneticist and evolutionary biologist.

“Dear Theodosius, what you said is true. Nothing makes sense without evolution,” sings Fox, who refers to parasites and autoimmune diseases and caps the video with a charming bit of humor.

Spanish education major Christin Journell created an infographic titled “Race is a culturally rooted category.” Journell said the course taught her that race is actually a cultural ranking of physical features rather than a biologically based concept. That knowledge, she said, enables people to identify thoughts that may unknowingly be causing racism and change those thoughts to be more inclusive and equity-based.

Around 70% of classes at Wright State are conducted remotely to limit the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Hubbard’s introductory course of 100 students used a peer-grading platform called Kritik to submit their work, give feedback to up to five of their classmates’ submissions and then rate the feedback received from their classmates. Her upper-level course of 26 students submitted their work for detailed feedback from Hubbard alone.

“In addition to being incredibly fun to grade, I was humbled by my students’ submissions,” Hubbard said. “Some tried a different format each time, some brought in personal stories and were vulnerable in sharing their own lives and experiences with the course content. I learned a lot myself about the power of creative expression. In fact, I noticed that a number of students who didn’t do well in the traditional weekly quizzes shined brightly during the creative assessments.”

Journell said having creative assessments in place of exams enabled her to look deeper into each topic or lesson.

“For example, whenever I study for a test in any course, it feels like I only focus on the top layer of a subject and I don’t really think about the many different and deeper layers that a topic, such as race, does have,” she said. “Having to complete a project for these topics made them much easier to review and comprehend, and it made this online class much more interactive and fun.”

Fox said projects that require students to explain concepts as if they were sharing information to people with no knowledge of the material encourages revisiting the concepts and breaking them down, which in turn solidifies one’s own knowledge.

“The creative assessment specifically was a breath of fresh air when it comes to testing because it allowed me to combine concepts from class with my second major – art – and activities that I enjoy, like singing,” she said. “Because of those creative freedoms and the confidence, I’ve gained in what I know, the creative assessment is definitely a form of learning measurement I would love to see in more classes, online and in person.”

Hubbard said she received emails from some of her students explaining how helpful teaching someone else was in cementing their own understanding of the materials.

“To be fair, there were some students who preferred traditional essays and let me know,” she said. “That said, creating a variety of opportunities for students to share their understanding of materials and to stretch themselves benefits everyone’s learning, even if it isn’t the preferred format.”

This semester, Hubbard plans to use these types of assessments and tools like Kritik in all of her courses because of the value of seeing others’ work, learning from one another, and practicing the important skills of productive critique and feedback.

Hubbard said the new teaching approach all stemmed from a realization in her pre-COVID-19 courses. She noticed that some students are really good at multiple-choice exams while others are better at explaining what they have learned. Ideally, Hubbard realized, students should be able to explain what they have learned to someone else, but they often need practice.

“The real ‘aha!’ moment was pre-COVID in an activity on the methods of scientific inquiry, where I explained the idea of hypothesis testing and methods of developing scientific theories,” she recalled.

Hubbard first asked her students to evaluate statements as either potential hypotheses or possible scientific theories given information or statements that were neither specific enough to be a hypothesis or broad enough to be a theory. When provided with multiple-choice options, most students could identify the hypothesis from the options, but few could articulate a clear hypothesis.

Then Hubbard gave the students a research question in anthropology and some basic information and ask them to develop a hypothesis. Few could articulate a clear hypothesis, with many trying to Google new information to generate alternative “theories.”

“Through this activity, our class was able to then review the submitted hypotheses and review how the hypotheses did or didn’t meet the basic criteria,” Hubbard said. “During the remainder of the term, I could walk students back to this initial activity about how science does (or does not) work. By the end of the term, students’ answers to essays about the nature of science and methods of inquiry were detailed, nuanced and correct.”

Glowing grad

Glowing grad  Wright State’s Homecoming Week features block party-inspired events Feb. 4–7 on the Dayton Campus

Wright State’s Homecoming Week features block party-inspired events Feb. 4–7 on the Dayton Campus  Wright State music professor honored with Ohio’s top music education service award

Wright State music professor honored with Ohio’s top music education service award  Wright State’s Industrial and Human Factors Engineering program named one of top online graduate programs by U.S. News

Wright State’s Industrial and Human Factors Engineering program named one of top online graduate programs by U.S. News  Student-run ReyRey Café celebrates decade of entrepreneurship at Wright State

Student-run ReyRey Café celebrates decade of entrepreneurship at Wright State