With constant images and reports from television, newspapers, the internet and social media saturating the senses, people would have to be living under a rock to escape the barrage.

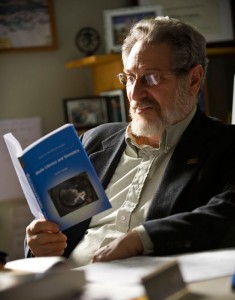

“People around the world spend an extraordinary amount of time every day consuming media,” said Elliot Gaines, Ph.D., associate professor of communication at Wright State University. “A lot of the time, we’re not even aware that the information that we carry with us is from the media.”

Beyond the 24-hour news cycle, both advertising and entertainment influence perceptions, attitudes, lifestyles and the ethics of society in interesting, yet subtle ways.

So how do we intelligently sort it all out and make sense of how media affects our view of the world?

Gaines discusses the answer in his new book, Media Literacy and Semiotics. Semiotics is the study of how signs communicate meanings, such as those in language and images.

“The purpose of this book is to provide tools to help people think critically about the media,” Gaines said. “Everybody has opinions, but very few people know how to validate beliefs shaped by the media.”

Gaines says the media have taken over the ancient role of campfire storytelling that humans have engaged in since the dawn of time.

“Basically stories tell us, This is the world we live in; these are things that happen; and these are the ways that we can respond,” Gaines said. “Long ago, we listened to people we knew, but now we live in a world where media have replaced our traditional storytellers.”

Television and the audiovisual media are better at communicating emotion than cognition, or knowledge through careful reasoning, Gaines says.

“The media wash over us in many ways, and we experience emotional content much more potently than we do intellectual content,” he said. “So people have a tendency to react to their feelings rather than using media as an information source for rational decision making.”

And media use repetition to normalize ideas, he says, taking advantage of the human tendency to accept something because it has become familiar. In addition, he says, media are accountable to market forces, and their popularity is based on a business model of success. The goal of commercial media is to attract an audience.

“Media are valued mostly because of popular appeal, not because they’re providing something meaningful to society,” he said.

The line that separates news and objective reporting from opinion and editorializing is blurring and can be difficult to identify, Gaines says.

People usually concede the power media has over the masses, he says, but don’t believe their own ideas are being molded, shaped or manipulated. And people bring their own predetermined values and knowledge when they consume news or entertainment media, he says.

“We all think that we’re well informed or at least that we’re right in our values and beliefs. People tend to hold fast to their opinions more than they seek facts,” he said. “And when you choose non-fiction media, you select what appeals to you. For example, people who tune in to political commentators generally want to have their values and beliefs affirmed.”

Reporters, news anchors and others who deliver the news derive their authority from the audience that accepts them, he says. And he says the news messengers can manipulate the emotions of their audience.

“We can never accept the absolute authority of the media to deliver information without taking stock of our own beliefs and checking our sources,” he said. “The only way one can find real solutions to complex questions is to think critically about new information and experiences, and verify knowledge.”

Gaines says semiotic methods show there are limits to verifiable factual information from the media.

“With a little patience and intelligence, semiotics can help people learn to think in simple, logical terms that can promote critical thinking and media literacy,” he says.

If all of society were media literate, Gaines says, the media would be held more accountable and public discourse might focus on understanding issues rather than reacting to rhetoric that triggers emotional responses and divisiveness.

“Exaggerated and distorted claims are intended to take advantage of fear and ignorance by demonizing individuals and rejecting options that may actually build common ground and promote the greater good for society,” Gaines said. “Media literacy would help people make distinctions between knowledge and speculations and identify real conditions and common values and goals.”

Glowing grad

Glowing grad  Wright State’s Homecoming Week features block party-inspired events Feb. 4–7 on the Dayton Campus

Wright State’s Homecoming Week features block party-inspired events Feb. 4–7 on the Dayton Campus  Wright State music professor honored with Ohio’s top music education service award

Wright State music professor honored with Ohio’s top music education service award  Wright State’s Industrial and Human Factors Engineering program named one of top online graduate programs by U.S. News

Wright State’s Industrial and Human Factors Engineering program named one of top online graduate programs by U.S. News  Student-run ReyRey Café celebrates decade of entrepreneurship at Wright State

Student-run ReyRey Café celebrates decade of entrepreneurship at Wright State