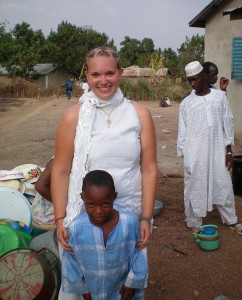

During a stint with the Peace Corps, Wright State graduate Corinna Lawrence worked in a health clinic, helped women start businesses and touched lives of many people in Guinea and Mali.

Sweating out sweltering temperatures, living without electricity and running water and being uprooted by bloody political violence, Corinna Lawrence’s stint with the Peace Corps in west Africa was … wonderful.

Despite the hardships, the Wright State University graduate worked in a health clinic, helped village women start businesses, touched lives and made a lifetime of memories.

“I often look back on my service and forget about the crazy sicknesses I got — the mosquito bites, the heat rash and the agonizing public transport,” Lawrence said. “What sticks out are the friends I made, the places I went and change I made.”

The Peace Corps traces its roots to 1960, when, as a member of the U.S. Senate, John F. Kennedy challenged college students to serve their country in the cause of peace by living and working in developing countries.

More than 215,000 Americans have served in the Peace Corps in 139 countries, the vast majority in Africa. Women constitute 63 percent of Peace Corps volunteers, whose average age is 28.7.

Over the years, many Wright State graduates have joined the Peace Corps, being assigned to far-flung countries such as Lesotho, which is surrounded by South Africa.

“It’s always a joy, but never a surprise, to hear about Wright State University graduates out in the world working with others to create positive change,” said Cathy Sayer, retired director of service-learning at Wright State. “There is such a culture of community engagement here, so many faculty incorporating service into their courses, so many members of the university community with a sense of themselves as citizens of both local and global communities.”

Lawrence graduated from Wright State in 2008 with a bachelor degree in international business and finance knowing that she wanted to do something big with her life.

So she joined the Peace Corps and was assigned to Guinea, a former French colony in west Africa and one of the poorest countries on the planet. She spent the next three months learning French and Pular, the local language of the Guinea village where she would work.

“I had no idea what I was doing,” she recalled. “When I arrived in Guinea and the plane doors opened, I was hit with a wave of heat, humidity and a bit of fear. I was suddenly immersed in a culture full of fast-paced movement, brightly colored fabrics and languages and smells previously unknown to me.”

Conakry, the capital of Guinea, suffers from overcrowding and poor sanitation. Few households have running water, electrical power is available only a few hours a day and temperatures can soar to over 100 degrees.

Getting around was a nightmare. Taxis and buses were jammed with passengers, had no air conditioning and would often break down.

“I would always bring at least two liters of water and enough snacks to last me a day because you never knew how long you would get stuck,” she said.

Lawrence was eventually placed in Douné, a small rural village about 170 miles away from the capital where she lived without electricity, running water and cellphone service.

She worked at the health clinic, assisting in medications, polio vaccinations, malaria prevention and weighing babies. (One in three children under the age of 5 in Guinea is chronically malnourished.)

Using knowledge she obtained at Wright State, Lawrence also helped start a savings and loan program with 50 village women. The women created a “bank” of money from which they could borrow small sums.

Statistically, women in Africa are more likely to spend their income on educating their children, providing for better health care and improving the nutrition for their family. That has the potential for breaking the cycle of poverty. Lawrence taught the women accounting, marketing, economic literacy and numeracy skills.

Two weeks after Lawrence arrived in Guinea, President Lansana died after a 24-year rule. Within hours, the military rose up and took power in what was called the Christmas Coup. However, the coup ended the next day when Capt. Moussa Dadis Camara declared himself the new president and laid out a timeline for free and fair elections.

But the elections kept getting pushed back, frustrating much of the populace. Nine months later — on Sept. 28, 2009 — things exploded.

When 50,000 supporters of the political opposition gathered at the soccer stadium in the country’s capital to demand that Camara step down, presidential security forces reacted. More than 150 people in and around the stadium were killed and more than 1,200 injured, the victims of shootings, stabbings and rapes. Camara said the troops accused of the violence were out of his control.

Lawrence heard the news on a radio while riding in a taxi, then gathered with friends to listen to reports on a shortwave radio.

“We sat in silence, sipping hot green tea and listening to the news unfolding,” she said. “I was scared for the country that had opened its arms to me and let me in. I was by no means in any danger in a small town so far away from the violence, but I could sympathize with the nation as it mourned the loss of life, the loss of freedom and the setback in the democratic elections.”

Within days, Lawrence and the other Peace Corps workers were evacuated from Guinea and whisked to the neighboring country of Mali. The evacuees were offered re-assignment. Lawrence chose to stay in Mali.

“I was extremely heartbroken to leave my Guinea community, especially since my projects were not finished, but was also excited to start a new path,” Lawrence said.

Reaching into the Sahara Desert, Mali is one of the poorest countries in the world. Its economy that relies on agriculture and fishing.

Lawrence was assigned to the town of Ségou and had to learn a different local language, Bambara, and get accustomed to sandstorms and Tô, cornmeal porridge with okra sauce.

Lawrence worked with a micro-finance bank, making loans of $100 to $500 to women. One woman used a $100 loan to start a roadside business.

“She quickly set up her wood-fired stove of three rocks and large cooking pot next to the main road and started selling her family recipe of cooked black beans with fresh onion,” Lawrence said.

The woman’s success led to her repaying the loan, then taking out a bigger loan to diversify food items to her business and repaying that. A few years later, the woman had her own restaurant and staff, serving local dishes such as peanut butter and tomato stew with vegetables over rice, cassava leaf stew on rice and cornmeal porridge with okra sauce.

“I am proudest of the work I did with micro-finance and being able to see the change firsthand that it made on people’s lives,” Lawrence said.

Lawrence finished her Peace Corps tour in 2011 and then took a job as a program manager for H.E.L.P. Malawi, a nongovernmental organization in the southern African nation of Malawi, where she and her husband lived in a national park.

After four years in Africa, Lawrence returned to the United States in 2012 and now works for an NGO in Washington, D.C.

Lawrence says the Peace Corps is known as the hardest job you will ever love.

“I set off for the Peace Corps with lofty goals of changing the world, but what really happened is the Peace Corps changed me,” Lawrence said. “It forced me to grow mentally, physically and emotionally; and I loved it!”

Adventures await

Adventures await  Wright State to expand nursing facilities to meet workforce needs and prepare more graduates for in-demand careers

Wright State to expand nursing facilities to meet workforce needs and prepare more graduates for in-demand careers  Wright State student-athletes make a lasting impact on local family with more to come

Wright State student-athletes make a lasting impact on local family with more to come  Wright State names Rajneesh Suri dean of Raj Soin College of Business

Wright State names Rajneesh Suri dean of Raj Soin College of Business  ‘Only in New York,’ born at Wright State

‘Only in New York,’ born at Wright State