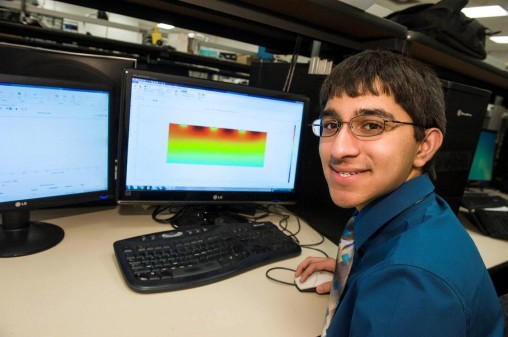

Shivam Sarodia, a senior at Centerville High School, has excelled in classes and working at Wright State’s sensors physics research lab.

The fifth-grader drifted around the library looking for an interesting book. Ah. There it is. A fantasy story thick with calculus and physics.

A year earlier, the boy and his classmates were asked to make A-to-Z books to build literacy. Many of the students used animal figures. The boy used astrophysics.

Today, the 17-year-old high school senior, Shivam Sarodia, is taking math and physics classes at Wright State University. The physics class is a weed-out course for college seniors and graduate students. Sarodia has an “A” and is at the top of the class.

Two years earlier, Sarodia’s mother drove her 15-year-old son to the lab of physics professor, Elliott Brown, Ph.D., the Ohio Research Scholars Endowed Chair in Sensors Physics at Wright State. Sarodia would spend time at the lab using multi-physics simulation software to perfect photoconductive devices that produce terahertz light waves.

“He is a good example of a wunderkind, a child prodigy,” said Brown. “He can pick up things so fast — anything related to math or physics or engineering or science of any sort that we’ve run into.”

Brown is an expert in terahertz radiation, which consists of the invisible light waves in the electromagnetic spectrum higher in frequency than microwave and lower than infrared light.

Terahertz imaging has been used for such things as inspecting foam insulation on the space shuttle’s external tank, looking for cracks and bubbles. And it is used to test semiconductors to determine if the quality is high enough to use in a computer chip.

“Every time we raised the bar a little bit, Shivam just kept jumping higher and jumping higher,” Brown said. “This year I suddenly realized that the kid is doing cutting-edge research.”

Born in New Jersey, Sarodia and his family lived in Cleveland and then Indiana before settling in Centerville, where Sarodia currently attends Centerville High School. His father is a physician at Miami Valley Hospital who specializes in pulmonary critical care.

“I’ve been interested in physics for as long as I can remember,” Sarodia said. “I guess I really like the problem-solving aspect of it. It’s very logical sort of thinking, but you’re working toward a single goal.”

Brown met Sarodia in the spring of 2013 at the Tech-Edge program, which brought in high school students and allowed them to work in a high-tech environment surrounded by researchers from the Air Force Research Laboratory.

Brown learned that the 15-year-old Sarodia had become bored with his electrical-engineering project in which he programmed a microprocessor. He wanted more of a challenge and was interested in physics research.

So “on a lark,” Brown invited Sarodia to work in his lab that summer.

“You would think that a 15-year-old is going to get bored after a couple of weeks and find better things to do or go off with his buddies,” Brown said. “I was expecting him to disappear, but he didn’t disappear. He kept coming back.”

Sarodia sponged up Brown’s lecture notes and breezed through graduate-level homework problems. He told Brown he wanted to be part of the solid-state electronics and physics work that is done at the lab.

“It was pretty tough to get up to speed at the beginning,” Sarodia said. “Most of my physics knowledge was skimming the surface of different subjects. So I had to delve into a lot of the specifics of semiconductor physics.”

Brown had just purchased a “cluster,” a set of computers that work together as a single system that have each node set to perform the same task and are able to outperform individual computers. So Brown put Sarodia on the cluster and a work station with a computer software tool that created multi-physics simulations.

“At first I thought this is going to be too hard for this kid,” Brown recalled.

What Brown didn’t know at the time was that Sarodia had just won a silver medal in the national Physics Olympiad.

“I used multi-physics software to model photoconductor devices and look at the thermal breakdown,” Sarodia said of his lab work. “I’ve learned quite a bit from the research since this is my first experience doing academic research in a physics context.”

Sarodia created simulations to test the reliability of photomixers, sophisticated devices made of exotic materials and used in the production of semiconductors. By last summer, Sarodia had refined his simulations to the point that Brown felt he had discovered something important enough to publish.

So Brown contacted organizers of the prestigious International 2014 COMSOL Conference in Boston, an annual event attended by top physicists and computer engineers. It is sponsored by the COMSOL Group, a high-tech engineering software company headquartered in Stockholm, Sweden, that provides solutions for multiphysics modeling.

“I sent an email saying we have this interesting simulation of important devices and would it be reasonable to send in our work if it is presented by a high school student?” Brown said. “Back comes an email saying something like, ‘That would be amazing. This would be the first high school paper we’ve ever had at our conference in its history.’”

Sarodia delivered a poster and made an oral presentation at the conference in October.

“The feedback was all good,” Brown said.

Brown said reaching out into the community to high school students — gifted or otherwise — demonstrates the university’s inclusive philosophy, open-mindedness and flexibility.

“We are not stodgy and set in our ways at Wright State,” he said. “We don’t have baggage here.”

Wright State is engaged in a $150 million fundraising campaign that promises to further elevate the school’s prominence by expanding scholarships, attracting more top-flight faculty and supporting construction of state-of-the-art facilities.

Led by Academy Award-winning actor Tom Hanks and Amanda Wright Lane, great grandniece of university namesakes Wilbur and Orville Wright, the campaign has raised more than $108 million so far.

Leamon Viveros, a researcher who works in the terahertz lab, said Sarodia’s performance has been extraordinary given his young age.

“He’s doing graduate student-type research. It’s amazing,” said Viveros. “It shows that there are opportunities. We have done everything we can to encourage brilliant kids to come join us. We are able to work with individuals and help them exert their maximum potential.”

Sarodia, who wants a career as a physics researcher, has applied to several colleges, including the prestigious Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

“It’s like fine art — when you see it, you know it,” Brown said. “And that’s the way it is with Shivam.”

Wright State receives $3 million grant to strengthen civic literacy and engagement across Southwest Ohio

Wright State receives $3 million grant to strengthen civic literacy and engagement across Southwest Ohio  Fitness Center renovation brings new equipment and excitement to Wright State’s Campus Recreation

Fitness Center renovation brings new equipment and excitement to Wright State’s Campus Recreation  Wright State University settles civil lawsuit against WSARC, now doing business as Parallax Advanced Research Corporation

Wright State University settles civil lawsuit against WSARC, now doing business as Parallax Advanced Research Corporation  Wright State senior paints a new path through fine arts internship

Wright State senior paints a new path through fine arts internship  Wright State recognizes Nursing Professor Kim Ringo for advancing international student success

Wright State recognizes Nursing Professor Kim Ringo for advancing international student success