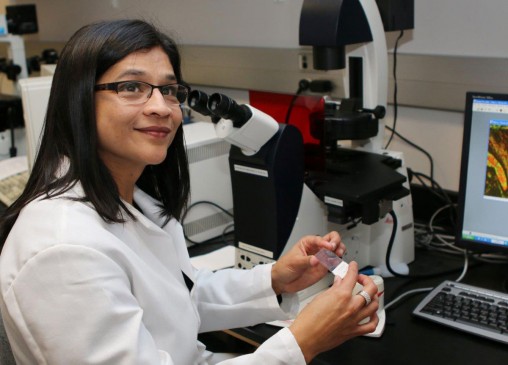

Wright State biochemistry and molecular biology professor Madhavi Kadakia uses a high-tech sequencer and her expertise in genetics to help diagnose and treat skin cancer, esophageal cancer and endometriosis.

Skin cancer, esophageal cancer and endometriosis are all on Madhavi Kadakia’s hit list. The Wright State University researcher has been using high-tech equipment and her expertise in genetics to help diagnose and treat these sometimes deadly diseases.

Kadakia, Ph.D., professor and chair of the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology in the Boonshoft School of Medicine and College of Science and Mathematics, is riding the wave of personalized medicine, an increasingly popular medical model that uses molecular analysis to customize health care. Genetics is a big part of that.

“Your genetic makeup is going to give a clue as to what drugs you’re going to respond to, what drugs you’re not going to respond to,” said Kadakia, “We have reached a point where we cannot only diagnose but treat patients based on their genetic makeup.”

Last year, Kadakia received a grant to purchase a next-generation sequencer, which accelerates genome sequencing by producing thousands or millions of sequences concurrently. The sequencer has revolutionized understanding of the complexity of cellular gene expression and provided deeper insights into the genomic landscapes of many diseases.

“It’s very important; it’s really a state-of-the-art technology,” she said. “We were very excited to be able to get it here at Wright State. People are really surprised at the equipment we have here.”

Earlier this year, Kadakia became involved in a research project with Dr. Steven Lindheim, professor in Wright State’s Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, at Premier Health. The project involves endometriosis, an inflammatory gynecological condition that produces chronic pelvic pain and infertility.

To diagnose endometriosis, it is often necessary to perform a biopsy, the surgical removal of tissue from the patient. The research project is instead taking bodily fluids including urine and blood and analyzing the DNA, proteins and metabolytes to create a panel of biomarkers that hopefully identify women with endometriosis, obviating the need to perform surgery to diagnosis this debilitating condition.

“You want to diagnose it quickly and try to come up with a way to diagnose it in a non-invasive manner,” Kadakia said.

The research is being aided by the Wright State University-Premier Health BioRepository, which provides patient bodily fluids and tissue samples.

As part of funding by the National Cancer Institute-National Institutes of Health, Kadakia is also studying the effects of vitamin D on cell survival in non-melanoma skin cancer.

Vitamin D is thought to be important to maintain a healthy immune system. While vitamin D can be obtained from exposure to the sun’s ultraviolet radiation, too much UV exposure can also cause skin cancer.

“So we’re really interested in how much UV radiation is good and how much is not good and how vitamin D regulates those genes,” she said. “We are focusing on non-melanoma skin cancer since the gene we are interested in is overexpressed there. Our studies will provide more insight into the role of vitamin D in cancer.”

Last year, Madhavi Kadakia received a grant to purchase a next-generation sequencer, which accelerates genome sequencing by producing thousands or millions of sequences concurrently.

Her research on esophageal cancer is in collaboration with Dr. Sangeeta Agrawal of the Dayton VA Medical Center.

To identify the pre-cancerous esophageal condition, biopsies must be conducted over time even though only a small percentage of the patients will actually get cancer.

“Can you imagine the anxiety?” Kadakia said. “Every time you go to the doctor, you don’t know if your condition has worsened.”

The goal of the research is to prevent the need for biopsies by genetically analyzing tissue and blood samples during different stages. The less invasive procedure would be more cost effective and reduce patient anxiety.

Kadakia grew up in Mumbai, India, with eight brothers and sisters. Her parents strongly emphasized the importance of education.

“Their mantra was, ‘If we give you education, you’re going to get what you want in life,’” she said. “I just can’t be thankful enough. I still talk to my dad and my mom every time I have to make a critical decision in my life.”

When Kadakia was working on her bachelor’s degree in India, she took a course on immunology and fell in love with it. So she studied it as she pursued her master’s degree.

“It was about that time that AIDS was all over the news,” she said. “I was so fascinated by immunology and I wanted to cure AIDS.”

When Kadakia was pursuing her doctorate in microbiology and infectious diseases at the University of Pittsburgh’s Graduate School of Public Health, virtually her entire department was doing AIDS research and she helped with clinical trials involving AIDS patients.

However, the bulk of her research was on human herpes virus #6 in bone-marrow transplant patients.

The patients often get a rash and a fever that is attributed to graft versus host disease (GvHD), in which the donated bone marrow views the recipient’s body as foreign and attacks it. But the herpes virus can also cause the rash and fever, and it can become activated when a patient’s immune system is compromised.

Kadakia was able to isolate 16 new strains of herpes virus #6 in bone-marrow transplant patients.

“As a result of that, doctors actually look for that virus rather than just assume it’s graft versus host disease,” she said.

Kadakia joined the faculty at Wright State in 1999.

“If you are really interested in science, this is the place you want to be,” she said. “There is a sense of community. Everybody has the same focus.”

Wright State is engaged in a $150 million fundraising campaign that promises to further elevate the school’s prominence by expanding scholarships, attracting more top-flight faculty and supporting construction of state-of-the-art facilities. Led by Academy Award-winning actor Tom Hanks and Amanda Wright Lane, great grandniece of university namesakes Wilbur and Orville Wright, the campaign has raised more than $108 million so far.

Kadakia escapes the pressures of the lab by painting. She has even created a tiny art studio in the basement of her house.

“When I’m painting, I don’t think of anything,” she said.

Wright State Police Department delivers major donation to Raider Food Pantry

Wright State Police Department delivers major donation to Raider Food Pantry  Wright State engineering and computer science students earn prestigious federal SMART Scholarships

Wright State engineering and computer science students earn prestigious federal SMART Scholarships  Wright State Police Chief Kurt Holden selected for prestigious FBI National Academy program

Wright State Police Chief Kurt Holden selected for prestigious FBI National Academy program  Wright State’s Raj Soin College of Business ranked among the best for entrepreneurs by Princeton Review

Wright State’s Raj Soin College of Business ranked among the best for entrepreneurs by Princeton Review  Wright State’s annual Raidersgiving draws hundreds

Wright State’s annual Raidersgiving draws hundreds