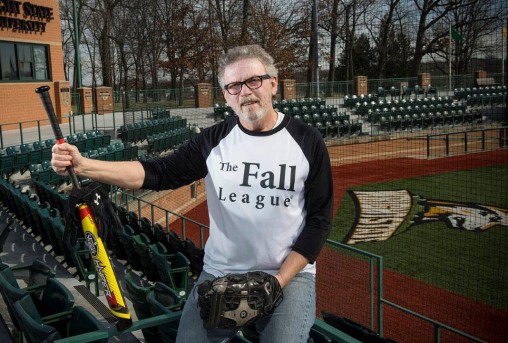

Tim Gebard, a 1991 Wright State M.B.A. graduate, produced “The Fall League,” a documentary film on senior slow-pitch softball in Dayton.

When he turned 40, Tim Gebard retired from decades of playing slow-pitch softball. But he missed it. So when he was in his late 50s, he began looking for a senior league.

It took a five-year search and a chance meeting with some players at the Young’s Jersey Dairy batting cages. But in 2012 — after 22 years of not playing — the Wright State University alumnus laced up his spikes for a six-week fall season in the Dayton City senior rec league.

“I was nervous because I didn’t know if my body would be able to handle it,” he recalled. “You can’t just go out there; you have to get into some kind of shape. And the guys are extremely competitive.”

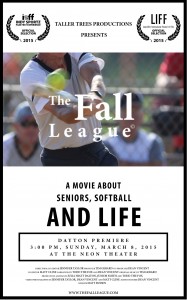

Gebard’s return to his field of dreams inspired him to produce “The Fall League,” a poignant documentary film about seniors who find purpose on the softball diamond. The title not only refers to the actual league, but is also a metaphor for the autumn of one’s life.

“Our generation is perhaps the first that can expect to survive for many years after retirement. But we don’t have to just sit around for 20 years; we can stay active,” said Gebard, 64. “The players in these leagues are survivors, and I think this movie shows a lot of that.”

The film features action video and slides as well as historic black-and-white stills of the players in their younger days. There are high-fives, fist-bumps, back slaps, attaboys and hugs.

The film features action video and slides as well as historic black-and-white stills of the players in their younger days. There are high-fives, fist-bumps, back slaps, attaboys and hugs.

“When we’re out here, we’re 11 years old again,” one player says in the film. There are flashes of the glory days, from sizzling line drives to backhanded stabs of sharp grounders.

But there are also knee braces, limps, white hair and naps on the bench. Players have had hip and knee replacements, rotator cuff surgeries and cancer. Last season, two players suffered strokes while they were on the field. One player will turn 90 this year.

“One of the things that attracted us to this film is that when you have 120 people who have reached this age, they’ve all got stories,” Gebard said.

When people return to softball at age 60 or older, it can be a boost to their psyche. Off the field, they’re told that they’re too old to have meaningful jobs, too old to take part in risky activities and are just not cool anymore.

“But you get on the field and you’re succeeding at a level that people don’t expect. All of a sudden, you’re the youngest guy again,” Gebard said. “And it’s not just about playing the sport; it’s about having that sense of community, the camaraderie with those who have had similar experiences and are there to support each other.”

In 2013, more than 7 million people played organized slow-pitch softball in the United States, 67,000 of whom were 65 and older.

Although senior slow-pitch leagues didn’t exist in Dayton until about 1992, the city has a national reputation for the sport. For decades, Dayton hosted the annual national police softball championship, with the tournament attracting teams from around the nation.

In the early 1960s, slow-pitch softball was a huge sport in Gebard’s hometown of Springfield. As a young boy, he would help his father sell tickets at major national tournaments that would draw up to 20,000 people.

“I got to watch a lot of slow-pitch games, and these were guys playing at the highest level,” he recalled. “A lot of the guys I was watching then now play in these senior leagues.”

Gebard got his bachelor’s degree in sociology from Wilmington College and his Master of Business Administration from Wright State in 1991.

Over the years, he worked in management in the restaurant, health care, financial and high-tech industries.

Now a singer/songwriter who plays guitar, Gebard released his first CD at age 60.

Two years ago, he and a couple of friends he met through his music decided to make a documentary and came up with the softball idea. They wrote the narration, recruited Dean Vincent of Studio D as co-producer and used music from Gebard’s CDs for the soundtrack.

“We knew there was no way we could work from a script,” Gebard said. “We felt like we had to let the players tell the story. And I didn’t want it to be a home movie; if we were representing these players, it had to be a real movie.”

Tim Gebard worked in the restaurant, health care, financial and high-tech industries and is now a singer/songwriter who plays guitar. His songs make up “The Fall League’s” soundtrack.

In addition to player and spouse interviews as well as game and practice footage, the producers interviewed experts on aging and psychology.

They also filmed at Louisville Slugger to talk with an expert on sports technology. Gebard says a case can be made that technology has enabled senior players to continue to play and even enhanced their performance.

“Shoes are better, gloves are better, balls are more high-tech. The bats especially are a lot different,” he said. “They really allow senior players to still hit the ball well, even in their 70s and 80s.”

In Indianapolis, the producers interviewed members of the Wounded Warrior Amputee Softball Team, many of whom are Iraq and Afghanistan veterans. And many players in the Dayton leagues are also World War II, Korean War and Vietnam War veterans, who have all had different military experience.

“While politically we may not all agree on a lot of things, when we’re on the field there is something about the team sport that brings us all together,” Gebard said.

The film also features Kathy Platoni, an assistant clinical professor at Wright State’s School of Professional Psychology and acclaimed expert in post-traumatic stress disorder and war trauma.

“She sees the therapeutic value of team sport in general, especially for people who are trying to reintroduce themselves into society,” said Gebard.

Technical challenges of the filming included dealing with the effects of the sun, wind and crowd noise on lighting and sound, players who were uncomfortable being on camera and insufficient crew and equipment to film the three games that were being played simultaneously.

But by the time they finished filming in October, the crew had more than 100 hours of footage. That was edited down to a 55-minute film that was finished Nov. 7. A week later, there was a private showing of the film at The Neon in Dayton for the players and their families. It produced both laughter and tears.

“We were trying to rush to get this done because we have people with real serious health issues and we wanted them to see it,” Gebard said. “Some of the guys you know are not going to be around.”

The film made its public premiere at The Neon on March 8 and was shown a second time after the first showing sold out. Dayton Mayor Nan Whaley issued a proclamation making it “Fall League Day” in honor of the film.

The Fall League has also been released on DVD and Blu-Ray at theFallLeague.com. The DVD is available in public libraries in Greene County, Preble County, Oakwood and Cleveland.

The film was selected to lead off the Indy Sports Film Fest Experience in Toronto, Ontario, on April 25 and also will be in Louisville’s International Festival of Film in October.

Four of the songs on the original soundtrack won honorable mention awards from SongDoor International Songwriting Competition. And a music video of the movie’s theme song — “That’s the Way (We Play the Game)” — is on YouTube.

The film also features Leon Speroff, author of “A Slow-pitch Summer: My Rookie Senior Softball Season,” a memoir of a physician returning to his first softball season in 40 years.

“Playing senior softball is a small triumph over the aging process,” said Speroff, who is in his 80s and plays in three senior leagues.

Milling around

Milling around  Wright State recognizes Nursing Professor Kim Ringo for advancing international student success

Wright State recognizes Nursing Professor Kim Ringo for advancing international student success  Wright State honors graduating students for distinguished doctoral dissertations

Wright State honors graduating students for distinguished doctoral dissertations  Top 10 Newsroom videos of 2025

Top 10 Newsroom videos of 2025  Museum-quality replica of historic Hawthorn Hill donated to Wright State

Museum-quality replica of historic Hawthorn Hill donated to Wright State