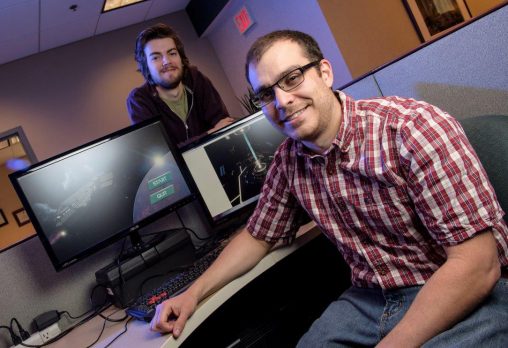

Noah Schroeder, right, assistant professor of education technology and instructional design, is working with several students, including Kenneth Deffet, to design a video game that can be used as teaching tool in classrooms. (Photo by Erin Pence)

Prison cells, space ports, generator rooms, catwalks and escape pods. They are all part of the infrastructure in a sophisticated sci-fi video game being developed by undergraduate students at Wright State University.

But it’s not just another video game. It’s a learning tool that promises to find its way into the nation’s K-12 classrooms to help students learn about everything from the French Revolution to Isaac Newton’s laws of motion.

“I really wanted to see if we could develop a game from start to finish on our own,” said Noah Schroeder, assistant professor of education technology and instructional design who is overseeing development of the game. “We’ve tried really hard to make it the quality of a game a student would want to play.”

The game is called the Student Centered Interactive Modular Performance-based Learning Environment, or SIMPLE. It is designed for the many teachers who have trouble finding an educational video game that matches the content they want to teach.

“We will be able to tell teachers to go to our website, download the game and copy and paste whatever questions they want to put into the game,” said Schroeder. “When their students go to play the game, the teachers will have their questions relevant to their class and their standards, and it will have taken them only 20 minutes to set it up.”

The video game is exquisitely detailed. Fine arts student Kenneth Deffet is doing the graphics, computer science student Alexandrea Oliver is the programmer, and computer science student James Morgan is creating the music and sound effects.

Jazz and country music can be heard coming from the apartments on the spaceship. There are wrinkles in the bedsheets. The elevator sounds like a real elevator. The sound effect was created by sliding file cabinet drawers.

The players are robots in the game. By answering the teachers’ questions correctly, they must escape a spaceship prison cell and navigate their way through doors, rooms, hallways, science labs and living quarters while avoiding security cameras.

The goal is to have multiple levels of the game so that teachers can use it for more than just one lesson. The teachers’ sets of questions will be added to a database that can be shared with other teachers.

The Wright State students, who have been working on the project for about a year, are currently beta-testing the game, looking for bugs.

“To me it’s been impressive what we’ve accomplished,” said Schroeder. “It’s been a really cool experience, not only seeing them work together but learning how to work as a cohesive team. Undergrads are some of the most creative people in the world if you give them something they want to work on.”

Schroeder grew up in Maryland and as a boy was into hunting and fishing. After attending the State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry, he transferred to Western New Mexico University, which enabled him to hunt jackrabbits.

He got his bachelor’s degree in biology from Colorado State University-Pueblo and then his master’s and doctorate in educational psychology from Washington State University.

When Schroeder was pursuing his master’s degree, he began to study virtual characters, fascinated by how video game developers choose the way characters look. His master’s thesis was on whether virtual characters are important in the learning environment.

One use of virtual characters is in Intelligent Tutoring Systems, which feature lessons and then questions about the material presented, with individualized feedback on the students’ responses.

“We found that virtual characters were more effective for learning for K-12 students than for college students,” Schroeder said.

The 27-year-old Schroeder joined the faculty at Wright State in 2014, in part because he wants to pursue research with scientists at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base and develop a game or simulation to help soldiers prevent or deal with post-traumatic stress disorder.

“The other thing I was really impressed with when I did my on-campus interview at Wright State was the acceptance of students with disabilities because I had never seen that anywhere else I had been before,” he said. “It felt real. It didn’t seem surface-level-we’re-doing-this-for-show. To me, that said a lot about the values of the school.”

Schroeder teaches in the educational technology master’s program in the College of Education and Human Services, offering classes in instructional design for digital learning and technology integration.

He is currently conducting several studies on multimedia learning principles to determine what virtual characters should look like and do to facilitate learning and how videos can be designed to make learning more effective.

“Virtual learning is a tool, a classroom is a tool, a computer is a tool,” he said. “I don’t think there is one good answer to how everything should be done.”

Wright State receives $3 million grant to strengthen civic literacy and engagement across Southwest Ohio

Wright State receives $3 million grant to strengthen civic literacy and engagement across Southwest Ohio  Fitness Center renovation brings new equipment and excitement to Wright State’s Campus Recreation

Fitness Center renovation brings new equipment and excitement to Wright State’s Campus Recreation  Wright State University settles civil lawsuit against WSARC, now doing business as Parallax Advanced Research Corporation

Wright State University settles civil lawsuit against WSARC, now doing business as Parallax Advanced Research Corporation  Wright State senior paints a new path through fine arts internship

Wright State senior paints a new path through fine arts internship  Wright State recognizes Nursing Professor Kim Ringo for advancing international student success

Wright State recognizes Nursing Professor Kim Ringo for advancing international student success