Psychotherapist and professor J. Scott Fraser is retiring after 23 years at Wright State’s School of Professional Psychology.

It was his first and last time on a luge. Scott Fraser was holding on tight as the sled hurtled down a twisting chute of ice at molar-rattling speeds.

Fraser loves the outdoors and is an experienced sportsman. He enjoys skiing, sailing, hiking and tennis. But riding a luge down an icy course in Michigan was a bit much.

“I’ll never do it again,” he said. “It’s very violent.”

Like luging, J. Scott Fraser, Ph.D.—psychotherapist, psychology professor and author—is also calling an end to his 23-year career at Wright State University. The 67-year-old is stepping into retirement Jan. 31.

“My work has been very gratifying; I’ve always loved what I do,” Fraser said. “And I’ve always loved working with students.”

Over the years, Fraser directed the internship program at Wright State’s School of Professional Psychology (SOPP) and then became the school’s associate dean and director of clinical training.

For the past 10 years or so, he has worked at Wright State’s Duke E. Ellis Human Development Institute in west Dayton, and on a therapy project training doctoral students and interns at South Community Mental Health Center in Kettering that involves rapid response and brief therapy with mental health clients.

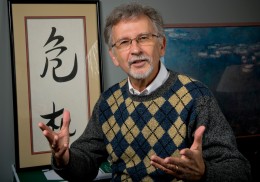

The youthful-looking Fraser looks every bit the psychotherapist/professor/intellectual. Bushy salt-and-pepper hair brackets a white beard. An argyle sweater and black loafers create a casual air. And the soft, soothing tones of his voice have a narcotic effect.

On the walls of his office hang landscape prints of French Impressionist Claude Monet and Chinese calligraphy that includes the symbols for danger, opportunity, chaos and order. But a cardboard box filled with Fraser’s office belongings signals that his journey through academia is coming to a close.

Fraser’s family history is oceanic. His grandfather was a ship’s carpenter on square riggers that sailed all over the world. Fraser’s father, an award-winning naval architect from Edinburgh, Scotland, moved to New England after Congress asked him to help refit the American Navy.

Fraser spent his early boyhood in the suburbs of Chicago, where his father later came to help build skyscrapers. When he was 12, Fraser moved to upstate New York.

He became interested in psychology in high school when he began reading the writings of Sigmund Freud, the Austrian neurologist who became known as the father of psychoanalysis, a series of techniques used to treat psychological problems.

“That really built a passion for me when I was in college,” he said.

Fraser obtained his bachelor degree in psychology from the State University of New York and went to California State University in Fresno to pursue his master’s in clinical psychology.

It was during the height of Vietnam War protests. There were demonstrations and firebombings. At one point, the National Guard was called in to protect a university computer center.

“There were lots of confrontations,” Fraser recalled. “It was an incredible, amazing thing we were in. Certainly, very much we were on a liberal, progressive side of things.”

Fraser then moved on to the quieter, more bucolic confines of Oxford, Ohio, to pursue his doctorate in clinical psychology at Miami University. While at Miami, he did a traineeship at Good Samaritan Hospital in Dayton, where in 1976, following his predoctoral internship year in Boston, he was offered a job directing the crisis and brief therapy team in community mental health.

The job was difficult, but Fraser reveled in it.

Scott Fraser’s latest book “Integrative families and systems treatment (I-FAST): A strengths-based common factors approach” will be published this year by Oxford University Press.

“It was Camelot,” he said. “A lot of the cases were at-risk cases—suicidal cases, sexual assault, domestic violence, psychosis, you name it. It was very much coming in at the point of crisis and then tipping it in a positive direction.”

As part of his job at Good Sam’s Crisis Unit, Fraser began supervising doctoral students from SOPP and in 1990 was hired by the school to direct its internship program. It gave him a chance to work with bright students from around the world.

“They’re special,” he said. “They come here and we select them because they are interested in social justice issues. We select them because they are interested in broadly defined diversity. They are not just interested in experimentation and brass instruments. It’s very much ‘How do I apply this?’”

Fraser said SOPP and Wright State have enabled him to do just about anything he wanted in developing programs and ideas.

“It’s a very creative supportive place,” he said.

Fraser has also worked with the Red Cross on disaster intervention by developing protocols and procedures for treating traumatized survivors of a variety of disasters. And he has traveled to northern Israel several times directing dissertations on how to treat victims traumatized by the fighting and civil unrest there and in other countries.

In 2007, Fraser’s book Second-order change in psychotherapy: The golden thread that unifies effective therapies was published.

Fraser says most psychological problems stem from getting stuck in a vicious cycle. And he says the most effective therapy—the golden thread—involves breaking people out of that cycle.

“All effective therapy thinks well of people, understands them, validates them, uses their language, but introduces a little something new and different that creates change,” Fraser said.

And he says change is often achieved by confronting rather than turning away from problems such as anxiety attacks or grief. He likens it to the Chinese finger trap, which requires one to first push the finger in before it can be pulled out.

“You’ve got to first go toward the grief,” he said. “You’ve got to make sure you understand your panic attacks, so you have to invite those in.”

Fraser also has a book with Oxford University Press that is coming out in the next few months titled Integrative families and systems treatment (I-FAST): A strengths-based common factors approach.

A product of 12 years of collaborative research, the book is already being used in Hong Kong, many places in Ohio and will likely find itself on the desks of psychotherapists as an evidence-based treatment manual for children and families.

Following retirement, Fraser plans to continue to write and consult.

He and his wife, Beth, who is also retiring from teaching, reside in Clayton. The couple’s children include a son who is a child and family therapist in the Columbus area and a daughter who works with at-risk teens in Illinois.

“I’m not going to slow down,” Fraser said. “Retirement will give me a chance to do some more fun stuff … just not on a luge!”

Centerville seventh grader wins Wright State University Regional Spelling Bee, advances to 2026 Scripps National Spelling Bee

Centerville seventh grader wins Wright State University Regional Spelling Bee, advances to 2026 Scripps National Spelling Bee  Three Wright State students win full year of tuition during Horizon League Championship game

Three Wright State students win full year of tuition during Horizon League Championship game  Walking through open doors

Walking through open doors  Adventures await

Adventures await  Wright State to expand nursing facilities to meet workforce needs and prepare more graduates for in-demand careers

Wright State to expand nursing facilities to meet workforce needs and prepare more graduates for in-demand careers