Wright State’s Special Collections and Archives published an online version of Milton Wright’s diary. Pictured are Jane Wildermuth, head of Digital Initiatives and Repository Services, left, and Dawne Dewey, head of the Special Collections and Archives. (Photos by Chris Snyder)

Wright State University is making the diaries of Milton Wright available online, giving worldwide access to the daily thoughts and reflections of the father of the Wright brothers.

The 41 black and brown leather-bound diaries have been in possession of the Wright State University Special Collections and Archives since they were donated by the Wright family in 1975.

Up until recently, the only way to see the diaries or their contents was to physically examine them at the Archives or to buy or borrow “Diaries: 1857-1917 by Milton Wright,” a book that was published by the Archives in 2000.

“I think the diaries help bring Milton Wright to life,” said Dawne Dewey, head of the Special Collections and Archives. “So it’s great to be able to have these online. I wish I would have had them online all these years just for my own research.”

Wright was a bishop of the Church of the United Brethren in Christ and father of aviation pioneers Wilbur and Orville Wright. He died in 1917 at the age of 88.

Special Collections and Archives published the diaries in CORE Scholar on Nov. 16, on the eve of the 189th anniversary of Wright’s birthday.

Wright kept an annual diary from 1857 to 1917, making daily entries and summarizing the year’s highlights in a narrative at the end.

Milton Wright kept a diary from 1857 to 1917, making daily entries and summarizing each year’s highlights.

Many of the entries are mundane. For example, he writes about going to buy a new pair of spectacles and about his daughter Katharine having her picture taken for her graduation from Oberlin College.

He lists his expenses and salary, family history, remedies for his aches and pains and important milestones in the lives of his children such as the time Wilbur was struck in the face with a hockey stick when he was a boy.

Other entries mark important historical events, such as marching with Katharine in a suffrage parade.

“And when the Great Dayton Flood of 1913 was happening, you read his diary entries and you get a sense of the catastrophic event that’s going on,” said Dewey.

There are entries about Wilbur and Orville’s flying achievements and about all of the dignitaries who came to Dayton to honor them.

“Milton calls them Wilbur and Orville or ‘the boys’ early on, and then after they became famous he calls them the Wright brothers,” said Dewey. “In one entry he talks about walking around downtown Dayton and people recognize him as the father of the Wright brothers. He’s concerned that they will become too prideful.”

Monday, April 5, 1909: “Called for my envelopes at the Post Office. They recognize and honor me as father of the Wright Brothers with considerable ado.”

Wright’s handwriting is beautiful and for the most part easy to read. But the original diaries were transcribed in the 1950s by volunteer congregants of the United Brethren in Christ Church in Huntington, Indiana, which was Wright’s denomination. Both the diaries and the typewritten transcripts arrived at Wright State along with the original “Wright Brothers Collection” from the Wright family.

Wright State’s world-renowned “Wright Brothers Collection” is the most complete collections of Wright material in the world.

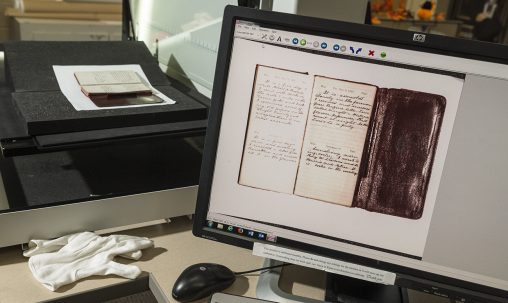

Jane Wildermuth, head of Digital Initiatives and Repository Services, led the 18-month digitization project. A total of 5,410 images were scanned. And metadata and keywords had to be created so that diary entries would be easy to find online in CORE Scholar.

“The diaries are pretty delicate to handle. People who were working on the digitization had to turn page by page and make sure nothing happened to them,” said Wildermuth. “It was quite a painstaking job.”

Digital Initiatives and Repository Services spent 18 months digitizing the diary project, scanning 5,410 images and creating metadata and keywords.

As editor of the diary book, Dewey read every single diary entry.

“I remember I would take the transcripts home and would come across something that Milton said or did,” Dewey recalled. “I can remember hollering to my husband or the kids: ‘Guess what he did today?’ And they would all run to another part of the house because they got really tired of him. But by doing that project, I really got to know him in a much more personal way.”

Monday, June 3, 1912: “Wilbur is dead and buried! We are all stricken. It does not seem possible that he is gone. Probably Orville and Katharine felt his loss most. They say little.”

Dewey said the diaries also offer a glimpse into family life at the turn of the last century.

“Even though we’ve heard about Wilbur and Orville’s flying experiments and their accomplishments, I think it’s important for people to understand that they were a part of a family, an ordinary family that lived in Dayton, Ohio,” she said. “It’s family history, it’s cultural history, local history and national history all rolled into one.”

Dewey sees Wright as a stern father who expected his children to grow up to be independent, yet dependent upon each other.

“He was the head of his household and conservative in many ways, yet he also promoted women’s suffrage and his sons when they said they wanted to fly,” Dewey said.

The diaries, which attract local researchers and researchers from around the country and the world, will still be available to see at the Special Collections and Archives.

“If you read his words and look at the photographs and touch the diaries, then you’ve got this magical thing going on,” said Dewey.

Wright State alum Lindsay Aitchison fulfills childhood space-agency dream

Wright State alum Lindsay Aitchison fulfills childhood space-agency dream  Wright State business professor, alumnus honored by regional technology organizations

Wright State business professor, alumnus honored by regional technology organizations  Wright State University Foundation awards 11 Students First Fund projects

Wright State University Foundation awards 11 Students First Fund projects  Gov. DeWine reappoints Board Treasurer Beth Ferris and names student Ella Vaught to Wright State Board of Trustees

Gov. DeWine reappoints Board Treasurer Beth Ferris and names student Ella Vaught to Wright State Board of Trustees  Joe Gruenberg’s 40-Year support for Wright State celebrated with Honorary Alumnus Award

Joe Gruenberg’s 40-Year support for Wright State celebrated with Honorary Alumnus Award