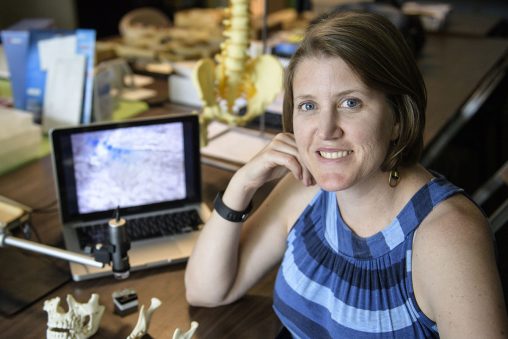

After Wright State moved all classes to remote delivery, Amelia Hubbard, associate professor of anthropology, turned her forensic anthropology course into a virtual experience.

A forensic anthropology class that usually has Wright State University students outside combing through staged evidence and replicas of human remains has been transformed into a virtual experience due to the need for remote teaching.

Amelia Hubbard, associate professor of anthropology, has held her forensic simulation exercise virtually, recreating the scene with photographs and video and then having her students analyze the remains in a virtual lab.

The scenario involves someone walking through the woods at Wright State and finding a leg in a tennis shoe. The students are tasked with finding the rest of the body, which they do in a decomposing log.

“The simulation allows them to practice what they’ve been learning,” said Hubbard, “and it definitely challenges them to see an experience even if these aren’t real forensic cases.”

She said the simulation creates the emotion and stress the students would experience at a real crime scene. They have to work carefully, but quickly, and learn how to document everything. Once they go back to the lab, they have to do a biological profile, analyze trauma patterns and investigate possible DNA.

“It’s almost like an interactive final exam,” she said.

In 2018, the class simulated a mock disaster involving an airplane crash on the Quad, mapping and spatially orienting the debris.

Hubbard is a biological anthropologist, conducts archaeological research and is a specialist in human remains. She has been called by police multiple times to identify remains even though none have turned out to be human.

Joining the faculty at Wright State in 2012, Hubbard has a bachelor’s degree in anthropology from Beloit College and her master’s and Ph.D. in anthropology from The Ohio State University.

Her course is designed to give students a theoretical understanding of what forensic anthropology looks like, the specialists they would work with and the challenges of the career. Many anthropologists interested in forensic science will go into related fields such as chemistry, genetics, osteology, anatomy or dentistry.

In mid-March, all classes at Wright State were moved to remote delivery through the end of the spring semester and most classes through the summer semester to try to limit the spread of the coronavirus (COVID-19).

In mid-March, all classes at Wright State were moved to remote delivery through the end of the spring semester and most classes through the summer semester to try to limit the spread of the coronavirus (COVID-19).

Hubbard said she already had all of her materials from the last time she taught the class, but had to take a crash course in remote teaching.

“My classes are all very hands-on and activity based, with assistance in class from undergraduate peer mentors,” she said.

Hubbard realized the potential for an online simulation while talking with a colleague at the University of Mississippi who had developed an online series of what she called “murder mysteries” for her students. One was about a fictional bootlegger in which she walked students through the history of bootlegging in the area and then staged plastic bones in a mock crime scene. Her colleague used a PowerPoint instead of more complex videos and found that students were easily able to follow along.

Hubbard’s students, who include anthropology and crime and justice majors, work with materials including maps, pictures of the scene and mockups of the “lab analysis.” The core details for the field recovery and lab analysis are presented in a PowerPoint with a five-minute video overview.

In the first part of the simulation — the field recovery — students read through the details of the scene and then open a PowerPoint presentation that shows a map of the area to be searched for remains and other evidence. The students have to determine how to arrange the search party and mark the evidence based on photos of the scene, decide when to ignore, document and collect evidence found near the skeleton. After taking notes on what they did and what they found during the search and what decisions they made, they complete an online activity based on the questions they’ve explored.

“It gets them to reflect on what they’ve learned the last few months,” said Hubbard. “It’s just that they’re not actually picking up the bones or drawing the map.”

During the second part of the simulation, students meet virtually in the lab to analyze their findings and try to reconstruct how the person died.

“It could be accidental. It could be a homicide. It could be any number of things,” Hubbard said.

Outside of this course, Hubbard also gives online lectures to her three classes and has “breakout rooms” for small groups of students to meet together for discussion. Students unable to attend the live lectures can download them for viewing later.

“I have definitely realized that I’m better at a lot of technologies than I thought I would be,” she said. “And there is a lot of technology out there that can solve some of the problems you might face.”

Hubbard said her students are starting to adjust to the remote delivery of teaching.

Hubbard said her students are starting to adjust to the remote delivery of teaching.

“A couple of students have reached out to me separately to thank me for making the transition as smoothly as I could possibly make it,” she said. “I think everything is working as well as it can.”

However, Hubbard said if remote delivery continues into the fall, she worries that she will never meet her new students face to face.

“Part of my classroom environment is building community and part of that is interacting together,” she said. “I’m going to have to figure out how you do that in a remote environment.”

Wright State business professor, alumnus honored by regional technology organizations

Wright State business professor, alumnus honored by regional technology organizations  Wright State University Foundation awards 11 Students First Fund projects

Wright State University Foundation awards 11 Students First Fund projects  Gov. DeWine reappoints Board Treasurer Beth Ferris and names student Ella Vaught to Wright State Board of Trustees

Gov. DeWine reappoints Board Treasurer Beth Ferris and names student Ella Vaught to Wright State Board of Trustees  Joe Gruenberg’s 40-Year support for Wright State celebrated with Honorary Alumnus Award

Joe Gruenberg’s 40-Year support for Wright State celebrated with Honorary Alumnus Award  Wright State’s elementary education program earns A+ rating for math teacher training

Wright State’s elementary education program earns A+ rating for math teacher training