A tuxedo worn by pianist, composer and bandleader Count Basie, who helped establish jazz as a serious art form, stands tall at the National Afro-American Museum and Cultural Center.

The clothing is a small part of an exhibit at the Wilberforce museum titled “Rhythm of Revolution: The Transformative Power of Black Art 1619 to the Present.”

Graduate public history students at Wright State University helped bring the exhibit to life by conducting research, selecting objects for the collection and writing up their history.

The exhibit, which presents a visual flow of cultural change driven by Black artists and activists, features photographs, clothing, paintings, a statue and other artwork. Panels of explanatory texts include titles such as “Slavery, Abolition and the Civil War,” “At the Pulpit,” “Music of a Free People,” “Harlem, New York,” “Black Freedom Movement,” “Black Arts Movement” and “Clothing and Style.”

“We wanted to tell the story of revolution and reclamation and resistance throughout American history,” said Hadley Drodge, assistant museum curator and a Wright State public history graduate. “But we wanted to do it in a way that didn’t just focus on the politics of these movements, but also show how artists are pivotal in creating cultural change. Not only do artists interpret these contemporary challenges that are happening around us, but they also kind of help us see a way forward.”

In the past year, the museum had to close temporarily because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“One of the things that’s very frustrating to somebody who is passionate about museums is seeing a museum with closed doors. All of these stories are kind of left untold,” said Drodge. “We immediately went into high gear trying to figure out how do we reach the public in a new innovative way.”

The museum exercised its online muscle, creating educational lessons for students who were remote learning and doing more webinars, attracting participants from around the country.

A tuxedo worn by Count Basie is featured in the “Rhythm of Revolution: The Transformative Power of Black Art 1619 to the Present” at the National Afro-American Museum and Cultural Center. (Video by Kris Sproles / photos by Erin Pence)

In May, the museum re-opened its doors, which included raising the curtain on the students’ “Rhythm of Revolution” exhibit for a four-month run through Aug. 14.

“This is such an important part of our history that for generations has been suppressed,” said Drodge. “What we are doing is just one small part to try to bring these stories out.”

The idea for the exhibit was born in a public history class on exhibits at Wright State during Spring Semester co-taught by Drodge, who herself has a master’s degree in public history from Wright State.

“We gave the students opportunities to help formulate this idea themselves along with having supervision from our staff,” said Drodge, who works with lead museum curator Rosa Rojas. “They did the research, the writing, chose the objects, did preparation on the objects for installation — the whole gamut.”

Each of the 10 students chose an era of time to focus on.

“What I love about this exhibit is that 10 different people with completely different backgrounds came together to dig up this history, interpret it in their eyes and to bring these stories to the public,” said Drodge. “It’s a very ambitious project. It’s a very long timeline with a lot to say in it. We hope what people can do is come to see this exhibit, get inspired by some stories and dig deeper.”

Derek Pridemore, who earned a bachelor’s degree in history and a master’s in public history from Wright State, co-taught the course along with Drodge.

“To have such a professional museum studies/public history program is incredible,” said Pridemore. “Bringing history to the public is one of the most important things historians can do.”

With the exhibit, Pridemore helped with writing and editing as well as cataloging and displaying the objects.

“The most gratifying thing is seeing the stories that have not been talked about on the walls and knowing that these people and these stories have been uncovered and put on display for people to learn about,” he said. “Creating art as an African American during these times was very dangerous.”

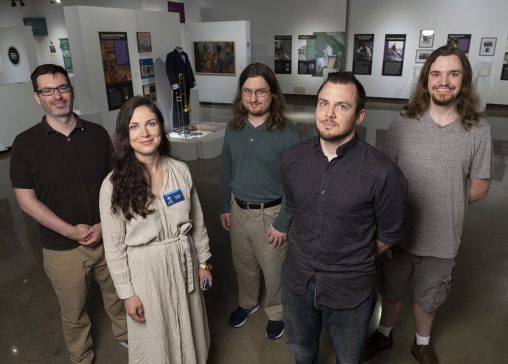

From left: Derek Pridemore, adjunct faculty member in history; Hadley Drodge, assistant curator and public history alumna; and public history alumni Daniel Willis, Travis Terracino and Michael Camp organized the “Rhythm of Revolution” exhibition.

Travis Terracino, who earned his bachelor’s degree in history from Wright State and graduated with his master’s in public history in May, developed a 1950s–1970s timeline that included artists during the civil rights movement.

The biggest challenge, said Terracino, was sorting through the massive amount of material and deciding what to exhibit, especially the things that were not so well known.

“We got to dive in to actual hands-on archives, looking at physical documents,” he said. “We’re not looking at reproductions; you’re looking at actual things that were touched by these individuals.”

Terracino said one of his favorite parts of the exhibit is a painting by visual artist Jeff Donaldson, co-founder of AfriCOBRA, a radical group of artists who wanted to separate from the “white gaze of art” and create a more Afro-centric, Black urban art for Black people.

Michael Camp, who graduated with his master’s degree in public history in May, focused on music and theater from the 1950s to 1979. Camp opted to display the Count Basie tuxedo along with a trombone from renowned jazz trombonist Booty Wood, who studied music at Dunbar High School in Dayton.

“In this era, you can’t talk about music without thinking about Motown,” he said. “Motown was founded in 1959 and still remains one of the biggest, well-known record labels, especially for African American performers.”

Daniel Willis chose the 1980s to the present day as his timeline.

“It’s really difficult because it’s really hard to find a place to stop when every day something new happens,” he said.

The deadline pressure and writing to convey a lot of information in a short amount of text were the most challenging things for Willis, who also graduated with his master’s degree in public history in May. His career goal is to work as an archivist.

“I really like digging through old boxes and finding neat stuff and telling people about it,” he said.

A foundation of support

A foundation of support  Wake-up call

Wake-up call  Centerville seventh grader wins Wright State University Regional Spelling Bee, advances to 2026 Scripps National Spelling Bee

Centerville seventh grader wins Wright State University Regional Spelling Bee, advances to 2026 Scripps National Spelling Bee  Three Wright State students win full year of tuition during Horizon League Championship game

Three Wright State students win full year of tuition during Horizon League Championship game  Walking through open doors

Walking through open doors