Research at Wright State University has made progress towards a treatment for preeclampsia. The serious blood pressure condition — which can occur during pregnancy or after giving birth — is estimated to cause more than 500,000 fetal deaths and 70,000 maternal deaths worldwide each year.

Research at Wright State University has made progress towards a treatment for preeclampsia. The serious blood pressure condition — which can occur during pregnancy or after giving birth — is estimated to cause more than 500,000 fetal deaths and 70,000 maternal deaths worldwide each year.

But, other than inducing early birth, research has yet to find a treatment for the disorder.

“Extreme prematurity all by itself is a major risk factor for mortality for the baby,” said David Dhanraj, an associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Wright State and practitioner at Miami Valley Hospital’s high-risk maternal health center. “We’ve had multiple cases over the last year where the mom’s preeclampsia and preeclampsia-related illness was so severe that we were forced to deliver her before the baby was viable just to save her life.”

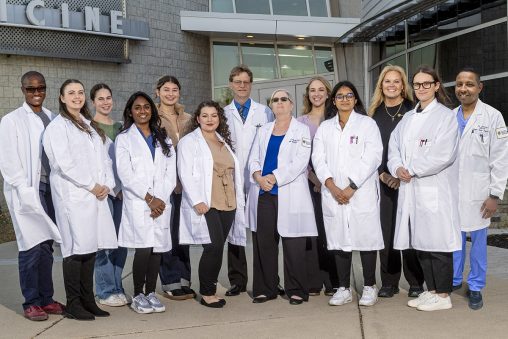

Dhanraj has been working in collaboration with Thomas Brown, professor and vice chair of research in neuroscience, cell biology and physiology at Wright State.

Their research is funded by the National Institutes of Health.

“For us to be thinking there might be some hope on the horizon is certainly what drives me towards working together and trying to move this along as fast as we can,” Dhanraj said. “So many of my patients have gone through some really terrible things and had some terrible losses.”

They’ve made accelerated progress in their attempt to treat the disorder, Brown said.

“We have to find a way to get at this that we just haven’t been able to,” Brown said. “This collaboration has really fueled how fast we’ve come. It’s resulted in a tremendous advance in what we knew from two years ago even.”

Brown said the complex biology of pregnancy has thus far stunted research in treating preeclampsia.

“You have to consider, are you affecting the mom or are you or are you affecting the baby or are you altering the placenta?” Brown said. “So you’ve got three things going on at one time.”

Modern technology and animal modeling have allowed progress in research at the cellular and sub-cellular level.

“We have a very good understanding of how the placenta develops,” Brown said. “We know what it should look like. We don’t know how or why the placenta does develop abnormally.”

Brown’s lab has found a potential source of the placental abnormalities associated with Pre-eclampsia. They’ve honed in on a gene called Hypoxia-inducible factor 1, or HIF-1.

“It’s very exciting, what we’ve been able to show is there seems to be almost a loop that continually pushes the system, driving our elevation in this normal HIF1- alpha protein,” Brown said.

Dhanraj recruits patients from his practice to contribute samples from their blood and placenta.

“Once he develops these models and really starts getting an understanding, we need to see if that’s really what’s happening in the human,” Dhanraj said.

Their work enlists Wright State undergraduates, master’s, Ph.D. and medical students.

“We understand that we can’t really do any of this without trying to push the next generation forward to continue this work,” Dhanraj said.

Walking through open doors

Walking through open doors  Adventures await

Adventures await  Wright State to expand nursing facilities to meet workforce needs and prepare more graduates for in-demand careers

Wright State to expand nursing facilities to meet workforce needs and prepare more graduates for in-demand careers  Wright State student-athletes make a lasting impact on local family with more to come

Wright State student-athletes make a lasting impact on local family with more to come  Wright State names Rajneesh Suri dean of Raj Soin College of Business

Wright State names Rajneesh Suri dean of Raj Soin College of Business