Wright State communication associate professor Jeffrey Alan John co-wrote a book about a 1940s shootout in Xenia, Ohio.

In 1946, two 20-year-olds from Cincinnati were accused of stealing a case of liquor and taking a wild road trip, stealing and burning cars along the way. Their journey ended in Xenia, Ohio, with a violent shootout that left one sheriff’s deputy dead and another wounded.

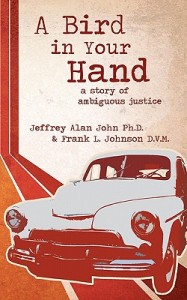

A Bird in Your Hand: A Story of Ambiguous Justice tells the story of these two young men, their crimes and their ensuing legal battles. The nonfiction book was written by Wright State University communication associate professor Jeffrey Alan John, with Frank Johnson of Kettering.

The project began when John and Johnson met at a dinner party and struck up a conversation about Xenia. Both men had ties to the city: Johnson had grown up there, the son of a local judge, and John had been a reporter for the Xenia Daily Gazette.

Johnson happened to bring up a case that his father had presided over: the case of Clarence Earl Tucker and Ernest Finley Evans. The discussion sparked a four-year collaboration to chronicle this true crime drama in writing.

The story goes like this:

Tucker and Evans were accused of stealing a case of whiskey from a hotel in Cincinnati and then embarking in a stolen car to the Akron area, to visit Evans’ wartime girlfriend. Along the way, they stole and burned two more cars on the side of the road.

En route home, when the men stopped at an all-night diner in Cedarville, a suspicious attendant called the sheriff in Xenia to warn him that two threatening characters were heading his way. After deputies stopped the car the men were driving, a shootout ensued that left Deputy Earl Confer dead and jailer Joseph Anderson and Evans wounded.

Based on court records, Evans was accused of pulling the gun and doing all the shooting while Tucker simply put his hands up and surrendered. However, both men were convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to life in prison.

According to John, the court actions are more intriguing than the crimes themselves. Why were both men treated exactly the same by the court when only one was accused of pulling the trigger?

The book puts a strong emphasis on this question, which John calls the “ambiguity of the local Ohio justice system.”

Sources for the book were Johnson’s own memories of the case and his correspondence with his father during the original trial. The authors were also able to interview the few parties still living, including a lawyer involved in Tucker’s subsequent appeal and Evans’ former girlfriend.

The rest of the facts came from digging in the public record. John spent many days at the Ohio Historical Society archives and Greene County archives poring through court records and newspaper articles from the last six decades.

John contrasted this type of research with researching modern-day events. For contemporary stories, all one needs is the Internet. Not being able to use the Web made this book more of a detective project.

“You have to find little morsels of information here and there and link them all together,” said John. “It wasn’t difficult for me to do that kind of research because it was a challenge with lots of rewards.”

The research might have been rewarding, but John said that the actual writing was hard work.

“I really wanted to make this a good read, ” said John, who teaches undergraduate journalism, mass communication and media graphics courses. He said he chose to view the book as simply long-form journalism.

That hard work seems to have paid off. Reviews of the book have been uniformly positive, especially in legal circles.

“Since it’s been published, many people have said that this should be read in law school,” said John. “It discusses heavy-duty legal concepts, but puts it into a story that’s worthwhile reading.”

Wright State celebrates homecoming with week-long block party

Wright State celebrates homecoming with week-long block party  Wright State baseball to take on Dayton Flyers at Day Air Ballpark April 15

Wright State baseball to take on Dayton Flyers at Day Air Ballpark April 15  Wright State joins selective U.S. Space Command Academic Engagement Enterprise

Wright State joins selective U.S. Space Command Academic Engagement Enterprise  Glowing grad

Glowing grad  Wright State’s Homecoming Week features block party-inspired events Feb. 4–7 on the Dayton Campus

Wright State’s Homecoming Week features block party-inspired events Feb. 4–7 on the Dayton Campus