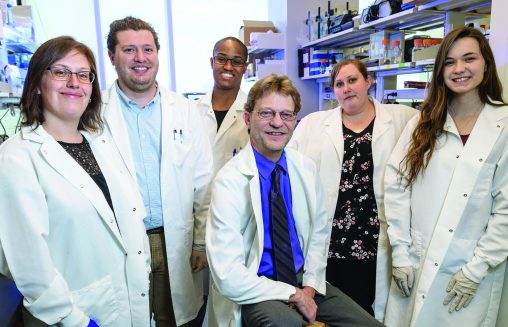

From left: Melissa Kaufman, Chris Waker, Chanel Keoni, Sarah Williams and Danielle Spanbauer with Thomas L. Brown. (center).

It was a nightmare. Five months into her pregnancy, Uohna June Thiessen’s blood pressure skyrocketed and she was hospitalized. For Thiessen, much of what took place there is a blur.

Doctors induced delivery but, sadly, she lost the baby. Even after that tragic event, her blood pressure remained high over the next few days. Thiessen began to have difficulty breathing and she suffered chest pains, the result of a swollen heart due to the high blood pressure.

Thiessen had developed preeclampsia, a pregnancy complication responsible for more than 76,000 maternal and 500,000 infant deaths worldwide each year.

“I did eventually get discharged from the hospital, but things didn’t get better for a long time,” she said. “I could not see a baby on TV or in the streets, as I would cry uncontrollably.”

When Thiessen was working toward her Ph.D. in biomedical sciences, she shared her story with Thomas L. Brown, vice chair for research in Wright State’s Department of Neuroscience, Cell Biology and Physiology.

“Clearly this is something that has left a permanent mark. How could it not?” said Brown.

Brown has spent the past 15 years studying preeclampsia, which can result from abnormal placental development and lead to a rapid and life-threatening rise in the mother’s blood pressure. It can also cause kidney damage and impair liver function. This can cause seizures in mothers and result in reduced growth and development of the baby.

Brown’s research, funded by the National Institutes of Health, advances the study of preeclampsia and has been internationally recognized. A paper on his research was published in February by Scientific Reports, a prestigious international journal.

“Babies born from a preeclamptic pregnancy are usually born prematurely and end up in the neonatal intensive care unit,” said Brown. “They are usually going to be very small. They could have physical problems, cognitive issues, and developmental delays.”

“To me, our research has made a significant scientific breakthrough in the field of pregnancy and preeclampsia because our model is so close to what we see in humans. We are one of a few labs in the world that is able to achieve placental-specific gene transfer.”

Brown said other research models don’t quite mimic preeclampsia because they usually affect the mother’s entire body and not specifically the placenta, the organ that supplies oxygen and nutrients to the fetus. The embryo and placenta grow in 2% oxygen initially, but after the first trimester the oxygen levels rise. If the placenta fails to recognize the increase in oxygen levels, the placenta will develop abnormally and mothers can develop preeclampsia.

Humans have a high level of the oxygen-sensing protein HIF-1, critical for placental development. This protein normally gets turned off in early pregnancy, after the first trimester. When the protein level stays on too long, it has been shown to be associated with the development of preeclampsia.

To directly test the involvement of HIF-1 in preeclampsia, Brown and his team conducted studies on pregnant mice. They created a mutant gene so HIF-1 could not be turned off during development—an animal model of human preeclampsia.

“This is a state-of-the-art model,” he said. “It’s very sophisticated, so it’s a little challenging. And it takes a very dedicated team.”

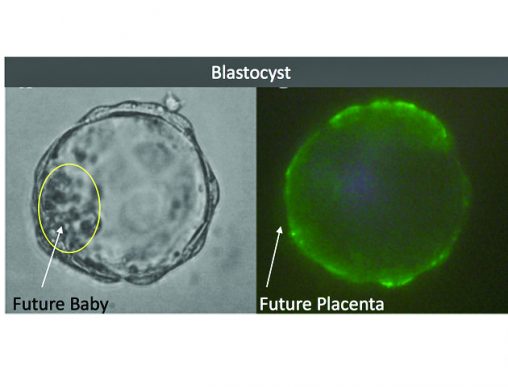

Left: Developing embryo three-and-a-half days after fertilization. Inner cell mass (circled) gives rise to the future baby. Right: Same embryo, tagged with green fluorescent protein to identify cells that will form the future placenta.

Having identified a molecular target, the researchers can now determine how to regulate it. “We can now look at several exciting avenues of research that could lead to new treatments for this devastating condition,” Brown said.

The research team will use promising new technologies that can carry drugs to the placenta without affecting the mother and baby.

“We are looking at identifying the molecular mechanisms underlying how preeclampsia happens, so that we can develop potential therapeutics and how to deliver those therapeutics without harming the mother or baby,” Brown said. “That’s been the challenge for quite some time. But I think we’re getting closer and closer to being able to do that, which is pretty exciting.”

Brown says that if a woman develops preeclampsia, she has a two-and-a-half-fold greater chance of having it during her next pregnancy. If a woman’s mother had preeclampsia during the pregnancy, the daughter also has a two-and-a-half-fold greater chance of developing preeclampsia. And if a man’s mother was preeclamptic during pregnancy, he has a twofold risk of fathering a preeclamptic pregnancy.

“What we see with women who had preeclampsia is that they are definitely at higher risk of cardiovascular issues when they become older adults,” said Brown. “They are also at higher risk of stroke and metabolic diseases such as obesity and diabetes.”

Thiessen says research into preeclampsia is critical to understanding what causes preeclampsia and to reducing the racial disparity in surviving childbirth in the United States. She says African American women have the highest rates of preeclampsia and are three to four times more likely to die in childbirth than women of other races.

Brown said the psychological impact of severe preeclampsia can be devastating to the immediate and extended family as well as the mother.

“The baby may be in intensive care for six to nine months,” he said. “They might die. You can’t touch them, but someone always has to be there. Jobs might be lost. Relationships can become very strained. It’s tremendously stressful for all involved.”

Thiessen said efforts are needed to better inform patients and families as well as medical personnel to the mental, physical and psychological aspects of preeclampsia and are of critical importance in treatment and care.

“The public must be made aware that preeclampsia is a very serious condition,” she said. “If more people understood what the disease is about and the impact it can have from a scientific, medical and personal perspective, it would help to deal with this harrowing experience.”

Support this research

The Endowment for Research on Pregnancy-Associated Disorders at Wright State, established by Brown, is intended to create a permanent funding source for long-term research on preeclampsia and pregnancy-associated disorders. To support this effort, contributions can be made at wright.edu/give to the Pregnancy-Associated Disorders fund.

This article was originally published in the fall 2019 Wright State Magazine.

‘Only in New York,’ born at Wright State

‘Only in New York,’ born at Wright State  Wright State president, Horizon League leaders welcome new commissioner

Wright State president, Horizon League leaders welcome new commissioner  Wright State celebrates homecoming with week-long block party

Wright State celebrates homecoming with week-long block party  Wright State baseball to take on Dayton Flyers at Day Air Ballpark April 15

Wright State baseball to take on Dayton Flyers at Day Air Ballpark April 15  Wright State joins selective U.S. Space Command Academic Engagement Enterprise

Wright State joins selective U.S. Space Command Academic Engagement Enterprise