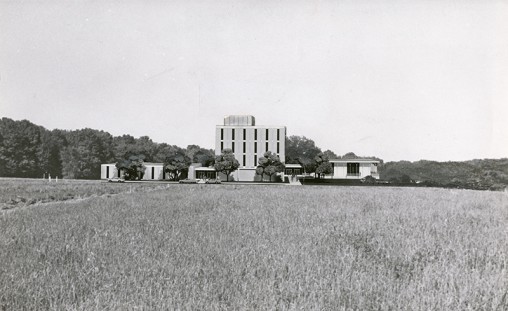

Allyn Hall before it open its doors in September 1964. (Photos courtesy of Wright State Archives and Special Collections)

It was born in a pasture and in 50 short years has grown into a muscular, thriving center of higher education. Today, Wright State University boasts high-tech classrooms, state-of-the-art research labs, world-renown faculty, a mammoth arena, a fast-growing branch campus and national recognition for its service to the community, the military and students with disabilities.

Leading to the birth of Wright State was Ohio Gov. James Rhodes’ effort in the early 1960s to place public higher education facilities within 30 miles of every Ohioan.

At the time, Dayton was a high-technology center with a special need for a highly developed labor force. In 1962, community leaders mounted a private capital fund campaign to secure a joint branch campus for The Ohio State University and Miami University that could be converted into a unified state university.

The campaign included contributions from thousands of manufacturing employees in weekly or monthly payroll deductions. In just two months, more than $6 million in cash and pledges had been raised.

The four principal founders of the school were Novice Fawcett, president of Ohio State; John Millett, president of Miami and chancellor of the Ohio Board of Regents; Stanley Allyn, chief executive officer of the National Cash Register Corp. (NCR); and Robert Oelman, successor to Allyn at NCR and board chair of Wright State through its first decade.

The seeds for Wright State were planted in a pasture 12 miles northeast of downtown Dayton. The chosen site had plenty of room for expansion, highway access and was close to Wright-Patterson Air Force Base — a dream come true for Air Force planners hungering for a nearby university.

A man by the name of Henry Bader went from farm parcel to farm parcel, buying land totaling 428 acres at a cost of about $756,000. Groundbreaking occurred May 31, 1963 — a clear, bright day that had the musical instruments of the Air Force band sparkling in the sunlight.

Gary Barlow, a high school art teacher and one of the first faculty members at Wright State, remembers coming up to see where the university would be built.

“It was grassland and fences and cows in the fields and so on,” Barlow recalled. “I looked over and I thought, ‘Oh my, did I give up a job to come over here for this? Something isn’t even up yet.’ Later, I came out and watched the big hole in the ground being dug for the first building.”

When students arrived at Allyn Hall on Sept. 8, 1964, the Dayton Campus of Miami and the Ohio State University was educationally in business. The four-story structure housed classrooms, laboratories, administrative offices, a library, a bookstore, a lounge and a vending machine room. There was one parking lot.

It is said that the paint on the walls of Allyn Hall was still wet when classes began. Barlow said the first class he taught was in a classroom that was actually still under construction. He said he would teach a little and then stop so the construction workers could install ceiling tiles. Then he would start teaching again.

“I’d asked the class a question, and the worker up on top of the ladder raised his hand. So I called on him and he answered, and he got involved in the lecture in the class,” Barlow said. “Not many people have the opportunity of being there while a university is built around them. It’s really a wild and crazy and wonderful thing.”

There were few administrators, so faculty members had to solve problems among themselves, often holding brainstorming sessions during brown-bag lunches.

Everything wasn’t housed in Allyn Hall. The biology lab was in the upstairs bedroom of an old farmhouse. The chemistry department claimed the kitchen for its lab because it needed access to water and the large sink.

Students and others coming to campus for the first time and needing directions were sometimes told to keep an eye out for an exotic animal farm off of Colonel Glenn Highway and “make a left at the ostrich.”

In 1965, ground was broken for the science and engineering building, which would become Oelman Hall, and for the classroom-library building, which would become Millett Hall. Two years later, Fawcett Hall and a university center were completed.

When the school’s enrollment reached 5,000 students in 1967, it was christened as an independent university. Despite a campus suggestion box filled with proposed university names such as Southwestern Ohio State, Five Rivers, Tecumseh, Shawnee and GreeneMont, the school was named Wright State after the Wright brothers.

The Fish sisters — Gerry, Kathy, Betsy and Sue — perhaps best epitomized the young, fast-growing university. The sisters cut a high profile when they were at Wright State in the 1970s and were heavily involved in campus activities.

They were all in the same sorority — Kappa Delta Chi. Kathy, Betsy and Sue were cheerleaders for the Wright State soccer and basketball teams. The house they rented on Colonel Glenn Highway near the university became a magnet for fellow students. The sisters’ spaghetti dinners would draw the Wright State soccer team. Renowned artist Bing Davis once showed up bearing large institutional-sized cans of corn and beans.

What is now the Student Union was built in 1969 followed by Hamilton Hall, the first dormitory, in 1970.

What would become the Lake Campus was originally affiliated with Ohio Northern University and offered courses in downtown Celina. It became a branch campus of Wright State in 1969 and over the years has experienced surging enrollments, a nearly doubling of bachelor degree programs, construction of residence halls and the purchase of nearly 40 acres for expansion.

Completed in 1973 on the Dayton Campus was Dunbar Library, a giant triangle resting on large pylons with a glass façade, a skylight roof and an atrium with an overlooking-balcony effect.

By the end of the 1970s, the university had 13 major buildings, including ones for the creative arts, medical and biological sciences, physical education and student activities, as well as a dormitory and school of medicine. The school’s unique tunnel system, one of the largest in the nation, attracted students with disabilities.

Wright State became firmly established on the higher education landscape in the 1980s. Its medical school graduated its first class in 1980, elevating the stature of the university. Rike Hall, home of the College of Business, was completed in 1981. The Nutter Center was built in 1990, a sports and entertainment arena that would draw millions of people to the campus over the years.

In 1992, the engineering school — which began in the 1960s as a small department in Fawcett Hall with a few faculty members and a single program — moved into the Russ Engineering Center, a newly built complex of classrooms and laboratories.

Construction of the engineering building was bankrolled by state funding and private donations. It was one of the first major fundraising efforts of the university, so everyone from President Paige Mulholland on down seemed to be engaged in raising money. It was hard work and sometimes involved a little luck.

Dean James Brandeberry recalled making a fundraising visit to Copeland Corp. in Sidney in hopes of getting a $1,500 donation, although he never mentioned an amount. He was told that the company’s budget cycle had just ended, but that a donation for Wright State would be made the following year. Sure enough, Brandeberry got a call from Copeland the next year from a company official who told him Wright State had been put in the budget for $50,000.

Led by coach Ralph Underhill, the men’s basketball team won the NCAA Division II national tournament in 1983.

The largest single private donation for the new engineering building came from Fritz Russ, an engineer and owner of Systems Research Laboratories. Russ was personally involved in designing the sign facing Colonel Glenn Highway to make sure it was visible to motorists so they would know Wright State had a strong program in engineering.

As the 21st century began, Wright State began to focus on research and helping build the regional economy. It would infuse it with millions of dollars and create hundreds of jobs. The Wright State Research Institute was created to be a front door to the university and work with local businesses, industries, academic institutions statewide, nearby Wright-Patterson Air Force Base and the NASA Glenn Research Center. The institute has since grown into a $33 million operation.

Regional summits were created to connect the university with business leaders, educators and elected officials to find out how Wright State could better serve their needs. Summit topics over the years included job-creation efforts surrounding military agencies and tips for businesses to make more effective use of technology.

Wright State’s culture of innovation was reflected by the state declaring seven Centers of Excellence at the university in neuroscience, human-factors performance, medical readiness, knowledge-enabled computing, the arts and other areas.

Wright State would also become more deeply engaged with the communities it serves.

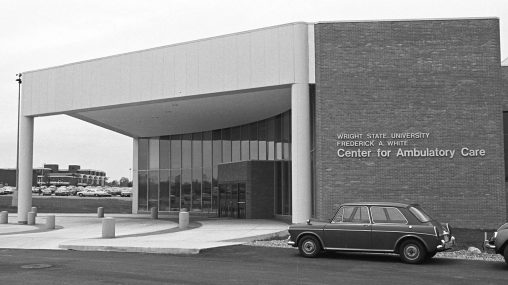

The Fred White Ambulatory Care Center was named after the first employee of the Dayton Branch of Miami University and The Ohio State University Campus.

The Dayton Regional STEM School was founded to offer high school students a relevant, real-world education that prepares them for college and the working world. The school opened in 2009 and in June 2013 graduated its first class — 52 talented seniors bound for the likes of Wright State, Emory, Purdue, Texas A&M, Ohio State, the Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology and other schools.

The Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching selected Wright State to receive its 2015 Community Engagement Classification, putting the university among just 83 U.S. colleges and universities to receive the classification for the first time. And for eight consecutive years, Wright State has been named with distinction to the President’s Higher Education Community Service Honor Roll, a national measuring stick of volunteering, community service, service-learning and civic engagement.

Wright State was recognized as a welcoming campus for veterans and military personnel. In 2014, Wright State opened the Veteran and Military Center, a 4,500-square-foot area designed to provide a welcoming space and support services on campus for veteran and military students. And the university created a special $100,000 scholarship fund designed to help members of the Ohio National Guard attend graduate school in what is believed to be the first program of its kind in the state.

By 2015, enrollment had reached a record 18,000 students, who were watching a building boom reshape the face of the campus.

Additions included a spectacular Neuroscience Engineering Collaboration Building. The building was the first of its kind to be intentionally designed to drive research interaction across disciplines, bringing 30 researchers from seven disciplines under one roof to understand brain, spinal cord and nerve disorders and develop treatments and devices.

The Student Success Center featured a 220-seat lecture hall and large active-learning classrooms loaded with screens, laptops and other cutting-edge technology. The Creative Arts Building was expanded and modernized, and the ribbon cut by the actor himself on the Tom Hanks Center for Motion Pictures.

What you have at Wright State is a “life-altering force for good,” said Hanks.

On July 1, 2017, Cheryl B. Schrader took the helm as Wright State’s seventh and first female president.

“This is the right time to be at Wright State,” said Schrader. “That is because it is an institution that has built up incredible momentum in the past decade and is just poised to move to that next level.”

Just getting started

Just getting started  Sparking creativity and innovation at Lake Campus

Sparking creativity and innovation at Lake Campus  Festival of Research celebrates experiential learning in College of Science and Mathematics

Festival of Research celebrates experiential learning in College of Science and Mathematics  From Dayton to rural Ohio: Wright State’s innovative approach to health care and education

From Dayton to rural Ohio: Wright State’s innovative approach to health care and education  Wright State’s motion pictures program enters new era of excellence in filmmaking

Wright State’s motion pictures program enters new era of excellence in filmmaking