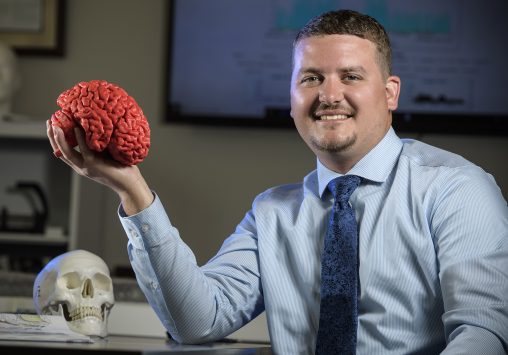

Wright State research engineer Matthew Sherwood receives $501,000 from the U.S. Navy to study the effects of fatigue and reduced oxygen. (Photos by Erin Pence)

Wright State University research engineer Matthew Sherwood has received $501,000 from the U.S. Navy to study the physiological reaction to fatigue and reduced oxygen.

The Cerebral Hemodynamic Studies of Hypoxia and Fatigue is a combined effort between Sherwood’s research team and the Naval Medical Research Unit Dayton.

The $501,000 award from the Naval Medical Logistics Command includes $308,000 for the two-year fatigue study and $193,000 for the one-year hypoxia study.

For the past few years, Sherwood has researched an initiative that trains people to control their brain activity while undergoing functional magnetic resonance imaging, or brain scans.

“We target a specific region of the brain, pull out the signals in real time, display those to the person and have them try to alter those signals,” he said.

The research is an effort to develop a technique that will eliminate or reduce the symptoms of tinnitus, or ringing in the ears.

Sherwood said tinnitus is the most costly medical condition to the military, even more costly than post-traumatic stress disorder and traumatic brain injury. He said the prevalence of tinnitus is probably because military personnel are often subjected to repetitive loud noise made by guns, bombs and jet airplanes.

He said tinnitus can negatively affect performance, causing annoyance, depression and lack of focus among those impacted.

Sherwood believes tinnitus is a condition that emanates from the brain itself and thus could be eliminated or reduced with the brain-control technique.

As part of the Navy award, Sherwood intends to investigate the use of the brain-control technique studied in the tinnitus research and apply it to finding ways to maintain performance when a person is fatigued or sleepy.

He said sleep patterns in the Navy are often disrupted, with missions that require one to be awake as long as 36 hours or being stationed on submarines where lights are on much of the time.

“If we can somehow alter the brain area that produces the sleep-regulating hormone melatonin and tell it to stop, then you shouldn’t be sleepy,” he said. “And you might be enhancing attentional processes as well during this process.”

The second prong of the research project has to do with hypoxia, a condition in which the brain is deprived of adequate oxygen. It often occurs in high altitudes or in underwater diving.

The award extends research already done in this area by Sherwood, who has induced hypoxia in human subjects while their brains were being scanned. They were given 9 percent oxygen, which is the equivalent of being at 20,000 feet. That is compared to the normal of 21 percent oxygen at sea level.

Hypoxia can result in vertigo and tunnel vision and even subpar performance for the following 24 hours.

Sherwood believes hypoxia causes the brain to divert its resources, reserving the limited amount of oxygen for things such as respiration and motor, visual and auditory function instead of emotions and other higher level executive brain functions.

“What we’re hoping to figure out is what’s going on here,” said Sherwood, who is collaborating in the research project with Ulas Sunar, associate professor of biomedical, industrial and human factors engineering. “This is really the first time this has been done.”

Matthew Sherwood earned his bachelor’s degree, master’s degree and Ph.D. in engineering from Wright State.

The long-term goal is to improve recovery from hypoxia. After people suffer hypoxia, they are often given 100 percent oxygen. But Sherwood’s research suggests that may be too much, that such a high percentage may be overwhelming the brain.

Sherwood grew up in Troy, Ohio. His father is an electrical engineer who was trained in the Navy, and Sherwood thought he was going to be an electrical engineer. But when he was a junior in high school — where he was a strong, math-focused student — he became interested in biomedical engineering.

After graduating from Troy High School in 2005, Sherwood attended Michigan Technological University in Houghton, Michigan. But he left and returned home to Ohio six months later to work and to “figure out who I was as a person.”

In 2007, he enrolled at Wright State to study biomedical engineering. He earned his bachelor’s degree in 2011 and began working on his master’s degree.

In 2012, he got a job at the Wright State Research Institute working as a medical research engineer. After earning his master’s degree in 2013, he began pursuing his doctorate in 2014 and three years later earned his Ph.D. in engineering on a biomedical track.

Milling around

Milling around  Wright State recognizes Nursing Professor Kim Ringo for advancing international student success

Wright State recognizes Nursing Professor Kim Ringo for advancing international student success  Wright State honors graduating students for distinguished doctoral dissertations

Wright State honors graduating students for distinguished doctoral dissertations  Top 10 Newsroom videos of 2025

Top 10 Newsroom videos of 2025  Museum-quality replica of historic Hawthorn Hill donated to Wright State

Museum-quality replica of historic Hawthorn Hill donated to Wright State