Jennifer Whitestone

Total Contact Inc. is more than a business to founder Jennifer Whitestone: it’s a mission.

Whitestone made the leap from federal employee with job security to startup business owner after using her biomedical engineering skills to help someone who had been badly burned in an accident—someone, as it turned out, she had known most of her life.

Since 1998, Whitestone’s small company in Germantown, Ohio, has been using surface-scanning technology to produce precisely fitted masks that promote healing and reduce scarring of patients who have suffered facial burns.

The company is a commercial outlet for medical technology Whitestone developed as a biomedical engineer in the Air Force Research Laboratory at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base.

Whitestone abandoned a comfortable career to pursue an unusual business that depended on new technology.

“It was a huge leap,” she agreed. A federal civil service job had a lot to like. “It was a decent salary. It was retirement and benefits and insurance and all those things. Job security,” she said. “I enjoyed my work there, but I just felt really driven to take this product to market.”

Her work at WPAFB was just what Whitestone had spent years preparing to do. Raised in Lebanon, Ohio, she attended her father’s alma mater, Virginia Tech, to get a bachelor’s degree in engineering science and mechanics with a concentration in biomedical engineering. After earning her B.S. in 1986, she went to work at the base and began working on her master’s in biomedical engineering at Wright State. She graduated in 1995.

In her first job, Whitestone worked with dummies—crash dummies, that is. “They’re used in the car industry to study car crashes,” she said. “In the Air Force, they’re used to determining what the body goes through in ejection scenarios.”

Whitestone wired up dummies with test instruments, gathered data in tests, and then used the data in computer models. “It was fun. It was a real hands-on job,” she said.

Her next assignment was in human engineering, which introduced Whitestone to three-dimensional surface scanning applications. “It was brand new, and I really became enamored with the world of 3-D scanning,” she said.

Whitestone was working in the field of anthropometry, which involves precisely measuring the human body. Her research was aimed at making better-fitting clothes and protective gear, such as oxygen masks for pilots.

The work utilized the medical imaging analysis Whitestone had learned at Wright State in her biomedical engineering program, and she saw potential medical applications for anthropometry—using surface scanning with lasers to measure wound healing, for example.

It was work that drew the interest of burn therapists from Miami Valley Hospital. In 1997, Whitestone recalled, “They came to me and said, ‘Hey, we have this patient who needs a burn mask. Do you think you can figure out how to make him one?’”

She had no way of knowing the patient who needed her help was someone she had known since childhood.

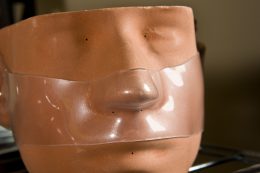

By precisely measuring facial contours, Whitestone’s company can make masks that reduce scarring for burn victims.

A burn mask reduces scar tissue buildup by pressing against the skin. Since scars grow continuously, a burn patient must wear the mask up to 23 hours per day for a year or longer. A precise fit is important for good results and comfort.

In the 1990s, the standard practice for making a burn mask was to cover the patient’s face with plaster to make a cast—a process that was uncomfortable at best and didn’t result in a perfect fit, Whitestone said.

“By using surface scanning, we’re going to capture the contours of the person’s face with sub-millimeter accuracy, and then we can replicate that,” Whitestone said. “We can also smooth the scars out ahead of time, so that the mold itself is a smooth representation of their face and not a scarred representation.” The end result is a plastic mask that fits better and helps the patient’s face heal better than earlier models.

When Whitestone finally met the patient, “I was shocked. I was very shocked,” she said. The patient was Jim VanDeGrift, who had coached football and track at Lebanon High School while Whitestone was a student there.

“I knew him very well. He and his family went to our church and I grew up with his kids,” Whitestone said. He had recently retired but had been severely burned in an accident with his lawn tractor.

Whitestone and others who volunteered for the project scanned VanDeGrift’s face with a laser and made the mask. But much of its success would depend on him. The retired coach would have to keep it on around the clock for it to be fully effective.

“Coach VanDeGrift was a very disciplined man, so he wore the mask like he was supposed to, and I started to see over the months that his scars were receding, and it was very dramatic,” Whitestone said.

The experience convinced her to make burn masks for other fire victims. “It became my passion. I wanted to get the technology out to other burn patients,” she said.

She set up her fledgling company in vacant space in the former St. Elizabeth’s Hospital in Dayton, then moved it to a storefront building in Germantown, near her home.

Total Contact remains a small company with just a handful of employees, but Whitestone said it isn’t sales or profits that drive her. “This business in many respects is a mission,” she said.

This ear cast illustrates the accuracy of surface scanning technology.

Even so, Whitestone has expanded Total Contact beyond burn masks.

For example, her company recently completed a three-year project for the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health to measure 951 firefighters across the country. The data will help equipment suppliers design safer and better-fitting gear, from gloves to fire engine seatbelts.

Also, a joint venture between Total Contact and another small company has created five patent applications with the goal of developing new medical products.

Whitestone gives Wright State a lot of credit for her accomplishments.

“I think Wright State was instrumental. I don’t think I would be where I am now without Wright State,” she said. It’s one of the reasons why she has stayed close to the university as an adjunct faculty member and advisor.

Whitestone said her company collaborates with Wright State to provide senior design projects for undergraduates in biomedical engineering. “We give them a project and we team the students up so there are generally two or three students on a team, and they work on the project and we work with them throughout the year,” she said.

“It’s a great program. I just love working with the students. They’re seniors, so they’ve had all the foundation of engineering for the undergraduate perspective, and then we give them a real-world problem, and it’s usually something we’re working on at the time, so we are very interested in it.

“So I haven’t gone far from Wright State,” Whitestone said. “Even though I graduated, I keep coming back.”

Wake-up call

Wake-up call  Centerville seventh grader wins Wright State University Regional Spelling Bee, advances to 2026 Scripps National Spelling Bee

Centerville seventh grader wins Wright State University Regional Spelling Bee, advances to 2026 Scripps National Spelling Bee  Three Wright State students win full year of tuition during Horizon League Championship game

Three Wright State students win full year of tuition during Horizon League Championship game  Walking through open doors

Walking through open doors  Adventures await

Adventures await