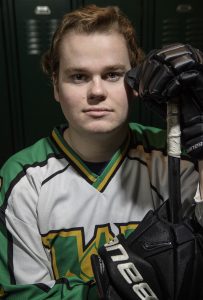

Scott Humes, a business major at Wright State, helped lead Team USA Deaf/Hard of Hearing Hockey Team to a gold medal in the third annual World Deaf Ice Hockey Championships. (Photos by Erin Pence)

He reads lips and uses hand signals. He also avoids checks by seeing reflections in the glass. It comes in handy when Wright State University junior Scott Humes is breaking away, body checking or crashing the net.

Humes is a hockey player, a good one. He is also deaf in both ears. Not only does he play on the Team USA Deaf/Hard of Hearing Hockey Team, but also competes for Wright State’s club hockey team against players who have no hearing disability.

Humes helped lead Team USA to a gold medal in the third annual World Deaf Ice Hockey Championships in the spring in Buffalo. The U.S. defeated Canada, 6-3, in the finals, avenging a 5-2 loss during pool play. Humes was named the U.S. player of the game following a victory over Kazakhstan in which he had two goals and an assist.

While on the rink with Team USA, Humes and his teammates have to use other methods to be “aware of when the play stops,” Humes said, since they cannot hear a whistle.

Those who rely on hearing aids or cochlear implants remove them for practices and games to avoid damaging the technology.

“Not everyone on the team signs or read lips. I speak primarily but also sign because I’ve learned it and I like to use it with those players who do sign,” he said. “We usually try to read lips or we have translators.”

After Humes was born, he was put on a machine that helps circulate blood through an artificial lung and because of this, he lost hearing in both ears. He had hearing aids for 14 years before choosing to get surgery for a cochlear implant.

He mainly relies on his cochlear and reading lips to understand.

Living in a world where there are more hearing individuals, Humes is faced with a few extra challenges, such as not speaking over the phone or being able to watch television if captions are not available. He occasionally struggles to understand professors, especially those with accents.

Born in Springfield, Massachusetts, Humes has lived across the country, moving frequently for his father’s career.

Humes attended Worthington Kilbourne High School in Columbus, where he competed in lacrosse and hockey.

But his journey in hockey didn’t begin there.

At the age of 3, Humes began skating with his father, Mike Humes, who played hockey growing up in Canada and coached his son. Mike Humes works for a hockey consulting business and teaches a course about the business of hockey at Athabasca University in Alberta.

Humes often visits Canada with his father and friends to watch professional tournaments in Toronto. He has met many professional hockey players, including Rick Nash and Wayne Gretzky. His favorite pro team is the Columbus Blue Jackets.

His skill on the ice is anything but silent.

Humes plays forward on both Wright State’s club hockey team, part of the American Collegiate Hockey Association, as well as Team USA, which he joined in 2016. He accumulated six assists for Wright State during its 2016-17 season.

A hockey team with players who are deaf or of limited hearing resembles a team of fully hearing individuals, except that concentration is done through the eyes instead of the ears. Shortened versions of signs are used, much like a baseball catcher’s hand signals.

Humes completed his language requirements for his degree in business with a focus on sports marketing through Wright State’s American Sign Language (ASL) courses. He provided examples of struggles and experiences that the Deaf community faces every day that were not mentioned in textbooks. He said most hearing individuals are unwilling to learn ASL to communicate with deaf individuals, so they are often forced to learn how to cope and communicate in a hearing world.

Being deaf has “taught me to accept people for who they are, and has helped me to be understanding of what people bring to the table,” Humes said. “It has taught me to be respectful of everyone, to reach out to them and help them communicate effectively or because they don’t have a lot of friends.”

In the summer of 2016 Humes faced a life-altering challenge: cancer.

Despite the diagnosis he still maintained a presence in his summer classes and hockey practices in between treatment.

His passion for the sport kept him hopeful.

Humes’ perspective on adversity and commitment to hockey was noticed, which earned him the Nick Wherling Award for courage, character and determination.

“I was in treatment a couple days before I finished chemo in July. We had try-outs in August and I had treatments for two weeks,” he said. “I just love hockey so I keep playing.”

His parents also played an influential role in his perspective towards adversity.

“My parents have helped me a lot,” he said. “My Mom and Dad have always taught me to be thankful and have good manners. So I try to keep that all of my life.”

“My parents have helped me a lot,” he said. “My Mom and Dad have always taught me to be thankful and have good manners. So I try to keep that all of my life.”

His mother, Jane Humes, works at Ohio State University’s Tissue Typing Lab. His older sister graduated with a business degree from Otterbein University in May.

Humes chose Wright State after a high school hockey coach of an opposing team recommended the university. He suggested Wright State to continue playing hockey and for the Office of Disability Services.

Wright State has “provided me with an education and good friends,” said Humes. “Wright State has helped me discover what’s out there, and it’s helped me navigate the real world. In high school, I was nervous about how I’d be in the real world and how I’d communicate effectively. Wright State has given me confidence.”

Wright State became an independent institution in 1967 and spent the next 50 years growing into an innovative leader in affordable and accessible education. In 2017, it celebrates its 50th anniversary and sets the course for the next half century.

Wake-up call

Wake-up call  Centerville seventh grader wins Wright State University Regional Spelling Bee, advances to 2026 Scripps National Spelling Bee

Centerville seventh grader wins Wright State University Regional Spelling Bee, advances to 2026 Scripps National Spelling Bee  Three Wright State students win full year of tuition during Horizon League Championship game

Three Wright State students win full year of tuition during Horizon League Championship game  Walking through open doors

Walking through open doors  Adventures await

Adventures await