To say that the faculty and staff in the Wright State College of Engineering and Computer Science have been busy since January would be an understatement. Beyond preparing for the spring and fall semesters, they have been reacting to major news that will greatly affect the college.

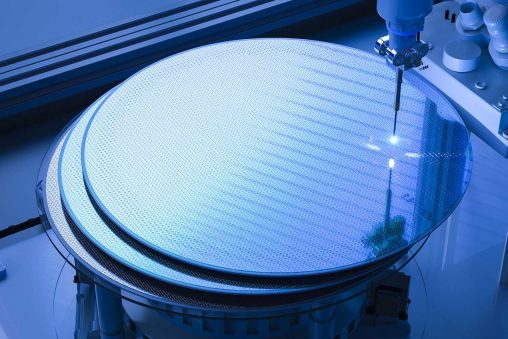

In January, Intel Corporation, headquartered in Santa Clara, California, announced a $20 billion investment to build two new factories in New Albany, Ohio, just northeast of Columbus. These factories will produce what has been increasingly in demand—advanced semiconductors. According to Intel’s website, the first phase of the project will bring thousands of Intel and construction jobs to Ohio and will attract other support operations and partners.

News of the investment was welcomed by Wright State. Subhashini Ganapathy, Ph.D., professor and chair of the Department of Biomedical, Industrial, and Human Factors Engineering, was not surprised by the announcement.

“Ohio is uniquely positioned as a center of manufacturing, so it made a lot of sense,” she Ganapathy, who is chair of Wright State’s Intel Initiative, an effort to support and build a long-term relationship with the corporation.

The factories are expected to be up and running by 2025, but Intel is moving fast. Construction is to begin late this year, and Intel is already anticipating the need to employ an educated workforce. To meet the demand, Intel will invest $100 million over the next decade in Ohio’s community colleges and universities in partnership with the U.S. National Science Foundation.

Ganapathy, who earned her doctorate in humans in complex systems from Wright State in 2006, is also a former senior user experience researcher for Intel. She worked there for seven years before coming back to Ohio in 2011. She has been meeting with Wright State alumni who work at Intel to learn more about what skills the company will need in the local workforce.

“We are looking to see if we have the capabilities that Intel wants and how we can engage with them so we can be as relevant as possible,” she said.

Wright State is among a group of leading research institutions from Ohio, Indiana, and Michigan that recently launched the Midwest Regional Network to Address National Needs in Semiconductor and Microelectronics to support Intel and its associated industries and expand opportunities for students and address its research and workforce needs in the state.

Intel’s education and research program will begin investing in August. Money will be allocated to Ohio’s educational institutions in the areas of curriculum development, faculty training, laboratory equipment upgrades, novel research to advance semiconductor fabrication, and student experiential opportunities. This funding is a major opportunity for Ohio, according to Brian Rigling, Ph.D., former professor and dean of the College of Engineering and Computer Science.

A rendering showings early plans for two new leading-edge Intel processor factories in Licking County, Ohio. Announced on Jan. 21, 2022, Intel’s $20 billion project spans nearly 1,000 acres and is the largest single private-sector investment in Ohio history. Construction is expected to begin in late 2022, with production coming online at the end of 2025.

“Directly for us, the implication is opportunities to train students in applications in which they haven’t seen much exposure. This will call for us to have a lot of partnerships,” he said.

These partnerships will be with businesses and other colleges like Sinclair Community College, Clark State, and the University of Dayton. Rigling said many of the jobs available at Intel will require a two-year degree, which Wright State only offers at its Lake Campus in Celina.

“At the two-year associate level, there will be more infrastructure to put in place. We already have programs in electrical engineering and mechanical and materials engineering, but we hope to add more classes to prepare students,” he said.

Rigling also said students have a lot going for them when it comes to jobs in the area. Many Wright State alumni are already using what they have learned and are working at Intel.

Stephanie Salas-Snyder has worked at Intel in Portland for eight years. She graduated from Wright State with a bachelor’s degree in biomedical engineering in 2006 and a master’s degree in human factors engineering in 2008. Her current job title is sales director of Microsoft Windows and devices.

“Wright State prepared me for a government job right out of college,” she said. “I remember the collaborative nature with professors. My time at Wright State helped me understand what it would be like in the real world. I honed my communication and multitasking skills there.”

Salas-Snyder worked as an engineer when she first got to Intel. While she’s no longer an engineer, she still uses those skills to engage with clients, engineers, and business partners.

“I became a technology ‘translationist.’ My interest in human factors has come full circle. A lot of the questions and conversations I have are focused on how to be more efficient and help people get the best user experience they can,” she said.

According to Salas-Snyder, Intel coming to Ohio helps level the playing field in relation to technology jobs, because many of these jobs historically have been located on the West Coast. She said the investment in Ohio will help spread Intel to a new and diverse population.

While engineering and computer science degrees are a major component for preparing Wright State’s graduates, other areas of study, including chemistry and physics, can help prepare the future workforce for jobs at Intel.

Jason Deibel, Ph.D., former chair and associate professor in the Department of Physics, has extensive knowledge of semiconductors. He said his department has already been putting resources into courses that will prepare students for Intel jobs.

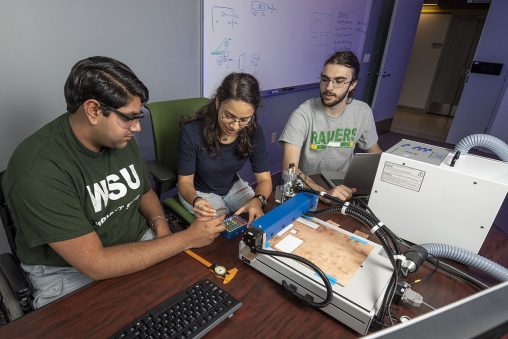

Wright State offers a “clean room” for teaching and research. According to Deibel, fabrication of microscopic or smaller devices must be done in a space that limits airborne particulates to an extremely low amount. Wright State’s clean room will be used to train students to work in such microfabrication facilities so they may become familiar with the necessary procedures and processes for semiconductor production.

“Few universities have the capabilities to replicate what Intel does. Intel knows that we can. We can teach the foundations with the clean room,” Deibel said.

Even before Intel’s announcement, Deibel said courses had already been created to utilize the clean room because the department saw the need to invest in this technology. This has led to increased collaboration among different departments and disciplines.

“A lot of people from a variety of backgrounds. That’s what I’m interested in,” Deibel said. “Can we make courses that are flexible across degree requirements? One thing that is critical is that Intel came to the Midwest for the potential workforce. If we don’t provide them those people, they will just bring them in from somewhere else.”

Wright State’s College of Engineering and Computer Science, College of Science and Mathematics and Raj Soin College of Business offer many degree programs to prepare students for jobs at Intel.

What should future Wright State students focus on if they want a career at Intel? Professors and alumni have some sound advice for them.

Rigling: “If they want to work for Intel, we have programs that will get them into the pipeline for those jobs. A lot of high school students don’t know much about these areas [Intel’s needs]. Try what sounds interesting and the earlier they can get out and get some job experience, the better.”

Salas-Snyder: “Diversity and inclusion are huge things at Intel. I’m a Hispanic, female engineer. I firmly believe that the more we can show students’ perspectives and ways of thinking, the better off we will be. Also, understand that Intel’s not just a business. It’s what the future of semiconductors is and their impact on the world.”

Deibel: “If they plan to stay in the area, all things are indicating expertise in engineering and physics. Go talk to faculty in the field. Pay attention and look for opportunities. Learn a programming language. The ability to communicate scientifically is important, but Intel doesn’t just want the knowledge. They want people with communication and planning skills.”

This much is known for sure: Intel’s building a significant presence in Ohio, and Wright State is poised to welcome the new neighbor and help with the high-tech growth on the horizon.

This article was originally published in the fall 2022 issue of the Wright State Magazine. Find more stories at wright.edu/magazine.

Centerville seventh grader wins Wright State University Regional Spelling Bee, advances to 2026 Scripps National Spelling Bee

Centerville seventh grader wins Wright State University Regional Spelling Bee, advances to 2026 Scripps National Spelling Bee  Three Wright State students win full year of tuition during Horizon League Championship game

Three Wright State students win full year of tuition during Horizon League Championship game  Walking through open doors

Walking through open doors  Adventures await

Adventures await  Wright State to expand nursing facilities to meet workforce needs and prepare more graduates for in-demand careers

Wright State to expand nursing facilities to meet workforce needs and prepare more graduates for in-demand careers