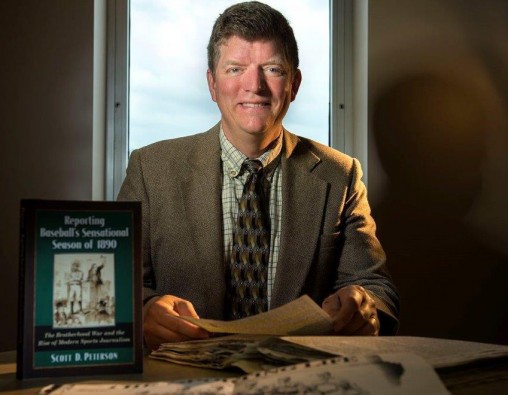

“Reporting Baseball’s Sensational Season of 1890,” new book by Scott D. Peterson, assistant professor of communication, examines the historic professional baseball season of 1890 and the beginning of professional sports journalism.

The historic professional baseball season of 1890 saw the players form a league of their own in an effort to break the financial chokehold of the owners. And the season marked the development of sports journalism as we know it today.

Fledgling journalist Etta Black reported it through the lens of female fans. And she did it without being able to interview the players and managers, which was considered improper. Instead, she relied on the “streetcar method,” gleaning information from conversations she would overhear.

These are among the nuggets that sparkle in “Reporting Baseball’s Sensational Season of 1890,” a newly released book written by Scott D. Peterson, Ph.D., an assistant professor of communication at Wright State University.

“I think it’s a book for baseball fans because it tells the story of a season that nobody really knows that much about,” Peterson said. “It’s also a book for people interested in journalism history to see how much has changed and how much has remained the same. This season really put baseball journalism on the path to where we are today.”

Peterson initially became interested in the 1890 season when he attended the annual NINE Spring Training Conference. The conference focuses on the study of all aspects of baseball, with particular emphasis on the game’s historical and social impacts.

One of the organizers of the conference had written a book on women in baseball and alerted Peterson to the existence of Black.

Peterson then began reading columns in “The Sporting Life,” a weekly newspaper that covered sports by publishing correspondence from contributors from around the country. Among them was Black, who offered to cover baseball from the female angle and to prove that a woman could write about the sport.

“I began reading her reports and decided there was a big story here,” Peterson said. “I was able to build a portrait of her by enmeshing myself in her reports. In 1890, a female journalist was rare enough, but to be a sports journalist was a significant story. And Black was able to break a few pretty big stories.”

Big or small, many were interesting. For example, Black reported on The Young Ladies of the Diamond, a club of female fans who would get locks of players’ hair and wear them in lockets painted with pictures of the athletes.

Scott Peterson’s book focuses on the work of three journalists, including Etta Black, who reported on baseball through the eyes of female fans.

In 1890, the players formed their own league to try to do away with the Reserve Clause, which bound a player to a team for life. A team could also sell a player outright to another team, and he would have no say. In addition, a player was paid for his performance on and off the field and could be penalized for bad behavior.

About two-thirds of the players in the Brotherhood Players Union formed the new Players League. The move forced the National League to fill its depleted rosters with young players who were not ready, players who were past their prime and players from the American Association, which was a lower-class major league.

“The season ended with nobody making any money,” Peterson said. “Attendance dropped off for both leagues because the public just got tired of the conflict.”

The Players League dissolved, and in 1891 things went back to the way they had been. The Reserve Clause would stay in effect for another 85 years.

“The baseball landscape would have been quite different if the players had succeeded,” Peterson said.

He tells the story of the 1890 season through the journalism of Black and two other writers — Henry Chadwick and T.H. Murnane.

“For the first time, baseball writing was significant,” said Peterson. “What was unfolding before them was important. They covered the business side very closely.”

He selected the three journalists to represent the owners, the players and the marginalized middle found in the class and labor struggle of the season. The book’s appendix features selected columns from the three journalists that are annotated by the author.

“The 1890 season marked the cusp of our modern age in three key areas: the celebrity status of baseball players and the popularity of the game, the rise of professional spectator sports as a viable and important economic force and the development of sports journalism,” Peterson writes.

Some newspapers covered teams in both eight-team leagues. Sportswriters began traveling with teams to cover road games. And reporters would call each other out when they reported rumors.

“These were the early days of journalism moving toward a profession through the development of professional standards,” Peterson said.

It took Peterson nearly four years to research and write the book, which has been published by McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers.

“I really immersed myself in 1890,” he said.” I read the newspapers of the time. I analyzed the reports of the three writers I selected.”

He even traveled to the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, N.Y., where he did research in the library there.

Peterson is also the author of several articles on baseball literature and culture. In addition, he is the fiction editor for “Aethlon,” the journal of the Sport Literature Association.

Wright State receives $3 million grant to strengthen civic literacy and engagement across Southwest Ohio

Wright State receives $3 million grant to strengthen civic literacy and engagement across Southwest Ohio  Fitness Center renovation brings new equipment and excitement to Wright State’s Campus Recreation

Fitness Center renovation brings new equipment and excitement to Wright State’s Campus Recreation  Wright State University settles civil lawsuit against WSARC, now doing business as Parallax Advanced Research Corporation

Wright State University settles civil lawsuit against WSARC, now doing business as Parallax Advanced Research Corporation  Wright State senior paints a new path through fine arts internship

Wright State senior paints a new path through fine arts internship  Wright State recognizes Nursing Professor Kim Ringo for advancing international student success

Wright State recognizes Nursing Professor Kim Ringo for advancing international student success