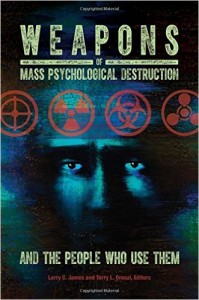

From left: Terry Oroszi, director of the Master of Science and Chemical, Biological, Radiological, Nuclear Defense Certificate Program in the the Boonshoft School of Medicine, and Larry James, professor in the School of Professional Psychology, edited “Weapons of Mass Psychological Destruction and the People Who Use Them.” (Photo by Will Jones)

The use — or threat — of weapons of mass destruction by terrorists also does psychological damage that can far outlast the physical destruction.

Experts at Wright State University have produced a new book that not only sounds a warning about the dangers of this psychological scarring, but offers profiles of terrorists, what motivates them, how they use the media, which weapons they choose and what can be done to fight terrorism.

“Weapons of Mass Psychological Destruction and the People Who Use Them” is authored and edited by Larry James, a now-retired U.S. Army colonel who led the effort to provide mental health services following the 9/11 terrorist attack on the Pentagon and is currently a professor in the School of Professional Psychology; and Terry Oroszi, director of the Master of Science and CBRN (chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear) Defense Certificate Program in the Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology at the Boonshoft School of Medicine and who coined the title of the book.

James and Oroszi will present a lecture on the book Thursday, Jan. 21, in the Endeavour Room at the Wright State University Student Union beginning at 7 p.m. This event is free and open to the public.

James and Oroszi will present a lecture on the book Thursday, Jan. 21, in the Endeavour Room at the Wright State University Student Union beginning at 7 p.m. This event is free and open to the public.

Contributing authors from Wright State include R. William Ayres, associate dean of the Graduate School; George Heddleston, chief communications officer at the Wright State Research Institute; Vikram Sethi, director of the Institute of Defense Studies and Education; Timothy Shaw, senior vice president and director of operations of the Advanced Technical Intelligence Center (ATIC) at the research institute; and Kelley Williams, associate director of the CBRN Defense Program.

The world has been reeling from recent terrorist attacks in Paris, Tunisia, Kuwait and San Bernadino, California. The attacks occurred at a time of high activity for the world’s most dangerous terrorist organizations such as ISIS and Al Qaeda, which continue to find ways to strike despite U.S. and other nations’ efforts against them.

James and Oroszi propose the inclusion of “psychological damage” in the definition of weapons of mass destruction.

“For an act to be classified as a WMPD event, it need not involve an agent capable of large death numbers or property damage,” they write. “The pivotal question is: Does an act — even if the loss of life or property is low — have the potential to also cause long-term, intense psychological harm to the masses?”

“We felt that there was an important P missing from WMD,” added James. “Terrorists are really going after that psychological piece.”

In his chapter, Ayres says the strategic advantage of terrorism is not so much in the amount of destruction, but in the overreaction of the target audience.

“Terrorism is ultimately about psychology — getting the opponents to change their behavior by changing the way they think, rather than by physical force,” Ayres writes.

Goals of terrorists can include getting attention, power, retribution, provoking overreaction, forcing change and mobilizing a political audience, he said.

The book paints a profile of terrorists, citing information that suggests they are often male, single and between 22 and 25 years of age. They are also often angry individuals who feel isolated from society, see themselves as victims of an injustice, are committed to a cause and believe they are making a difference.

James states that terrorists are often poor, uneducated and sometimes mentally ill. They often lack a strong father figure in their lives and a spouse or girlfriend who can provide a sense of reason. They feel disconnected from society and are vulnerable to promises from terrorist recruiters of community and fighting for a common cause.

James said terrorists use the media as psychological, tactical, strategic weapons and often carry out attacks in large media markets.

“In particular they target women and children,” said Oroszi. “If you see a woman or child tortured on TV, you’re going to be more psychologically damaged.”

The book also addresses the economic impact of terrorism, from the cost of the destruction itself, the increased cost of combatting and preventing it and the loss of tourism when people choose to curtail travel.

In his chapter, Sethi writes that the 9/11 terror attacks cost perhaps $400,000 to execute, but will ultimately cost the United States more than $5 trillion in what he suggests are the “costs of fear.”

James said psychologists can be instrumental in working with counterterrorism task forces or helping police departments develop profiles of terrorists. And he said psychologists can help communities deal with their fear of terrorism and counterbalance news reports on terrorism that alarm the public.

Oroszi says weapons of mass destruction are difficult for terrorists to obtain and use. She hopes the book educates the public about how the psychological damage can be a greater danger than the physical threat.

“The WMD the terrorists use are meant to create mass psychological distress,” Judy Kuriansky, clinical psychologist, trauma expert and chair of the Psychology Coalition of NGOs at the United Nations, writes in the book’s forward. “Thus, expanding the concept to WMPD is an approach that should be known by all psychologists as well as law enforcement, Homeland Security, politicians, policymakers, scientists, international relations experts and students of related disciplines.”

James and Oroszi say education is the most powerful tool in combatting terrorism.

“When we understand the psychology of terrorists, their tactics will lose their power,” the two write in the book’s final chapter. “Kidnapping of women or children, beheadings, hangings, torture or the use of CBRN agents — the fear will be replaced with a greater sense of community outrage.”

“They are not crazy, maniacal people like everybody thinks,” added Oroszi. “Their tactics are premeditated and calculated for the purpose of instilling terror. By writing this book we have provided a weapon to combat this psychological impact.”

Wright State baseball to take on Dayton Flyers at Day Air Ballpark April 15

Wright State baseball to take on Dayton Flyers at Day Air Ballpark April 15  Wright State joins selective U.S. Space Command Academic Engagement Enterprise

Wright State joins selective U.S. Space Command Academic Engagement Enterprise  Glowing grad

Glowing grad  Wright State’s Homecoming Week features block party-inspired events Feb. 4–7 on the Dayton Campus

Wright State’s Homecoming Week features block party-inspired events Feb. 4–7 on the Dayton Campus  Wright State music professor honored with Ohio’s top music education service award

Wright State music professor honored with Ohio’s top music education service award