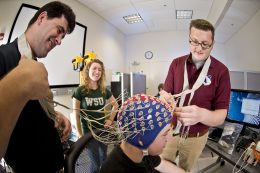

Justin Estepp (right) and Wright State engineering students Chris Meier, Sabrina Metzger, and Ethan Blackford (in cap) use eye-tracking and EEG sensors to measure cognitive state in a Human Effectiveness lab at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base.

Justin Estepp describes himself as “just a bench engineer.” But with a small army of student research assistants at his side in the Air Force Research Laboratory’s 711th Human Performance Wing complex at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Estepp is grinding out game-changing research at the intersection of engineering, neuroscience, and psychology that the United States Air Force views as a new frontier for achieving military superiority.

“We hear people say ‘mind reading’ a lot, but that’s not it exactly,” Estepp says, describing his research in monitoring cognitive state. “It’s a three-legged stool of applied or behavioral neuroscience: figuring out what technologies best monitor the physiology of a human, such as eye-tracking and EEG; how we can relate that physiology to their cognitive state; and then how we can augment a human’s performance based on that cognitive state.”

Estepp—who earned a bachelor’s degree in biomedical engineering from Wright State in 2006 and is finishing his master’s degree in the same field—is an associate research biomedical engineer in the wing’s Human Effectiveness Directorate, Warfighter Interface Division. He is among more than a half-dozen, up-and-coming Wright State grads managing research programs inside the fence in that directorate, researching how technology can enhance a warfighter’s performance in the sky, in space, or in cyberspace. Wright State grads are doing everything from researching how UAVs can fly by voice command, to evaluating new, noninvasive techniques to stimulate the brain to improve attention span, to optimizing displays so that pilots or airmen can better interpret images, among other areas.

The Air Force Research Laboratory, headquartered at WPAFB, manages the Air Force’s science and technology program, a $2 billion research juggernaut employing about 9,600 people. Its eight directorates emphasize a particular area of research, and for Human Effectiveness, the key word is “human.” It focuses on integrating biological and cognitive technologies to boost a warfighter’s performance in instances such as operating multiple unmanned aerial vehicles, or overcoming fatigue and loss of concentration while looking at computer screens.

In designer jeans and eyeglasses and Doc Marten boots, his blazer draped across a chair, Estepp belongs to a sophisticated, postmodern generation of engineers and scientists who will move up the ranks in their various directorates to lead the Air Force research agenda in the decades to come.

Out of concern for a shortage of scientists and engineers, AFRL has been cultivating a cadre of young technical talent to work in government labs instead of the private sector, so that when 40 percent of its workforce retires over the next two decades, the military maintains its technological superiority.

For engineers and human factors psychologists, AFRL is an opportunity to make breakthrough discoveries in fields such as unmanned aerial vehicles, modeling and simulation, sensors, cyberspace, intelligence and reconnaissance, and human performance.

Chris Meier, a Wright State student who hopes to continue working for AFRL after completing his master’s degree in biomedical engineering in 2014, is one of four Wright State engineering students working with Estepp as research assistants. “The private sector probably couldn’t touch the kinds of experiences we get here, from day one,” Meier said, who admits the initial attraction is in getting to play with technology’s latest toys.

But for a lot of students, the base is an intimidating black box. “I really had no idea research goes on at the base until I heard about it through classmates,” said Sabrina Metzger, a senior in biomedical engineering. Through contact with other Wright State students, and through faculty, Metzger found the research assistant positions in the Human Effectiveness directorate. “Once you get here, you realize it’s more laid-back than you think, and you have a lot of autonomy,” she says.

Estepp knows the value of these internships: like a lot of young professionals working at WPAFB, the Dayton native stayed in the area because of an interesting internship at the base that kept him here.

After graduating from Fairborn High School, Estepp joined the inaugural class of AFRL’s Wright Scholar Research Assistant Program in 2002, the summer before his freshman year at Wright State. The program enables high school juniors and seniors to work with AFRL researchers for 10 to 12 weeks on projects including testing materials, tracking data, creating databases, charting data, and computer modeling and programming. That introduction to AFRL led to engineering internships that kept him working in the lab all the way through completion of his master’s degree. In 2008, he joined AFRL as a full-time engineer.

When Estepp’s lab needs student research assistants, he often taps Wright State because it offers the only biomedical engineering program in the region.

From providing continuing education toward advanced degrees, to collaborations with faculty, to networking with other researchers, Wright State is “well positioned to facilitate a lot of collaborations” that would benefit the technical researchers in AFRL.

“There are a lot of us who will at some point work on advanced degrees, and Wright State is perfect for that,” because of its proximity and interdisciplinary programs. “And we have access to its students, just down the street. All in all, the university is a great resource.”

Wake-up call

Wake-up call  Centerville seventh grader wins Wright State University Regional Spelling Bee, advances to 2026 Scripps National Spelling Bee

Centerville seventh grader wins Wright State University Regional Spelling Bee, advances to 2026 Scripps National Spelling Bee  Three Wright State students win full year of tuition during Horizon League Championship game

Three Wright State students win full year of tuition during Horizon League Championship game  Walking through open doors

Walking through open doors  Adventures await

Adventures await