Christopher Oldstone-Moore, senior lecturer of history at Wright State, has spent more than 10 years researching and chronicling facial hair trends and will release a new book, “Brave Face: Beards, Shaving and the Cultural History of Manliness,” this year.

Aristotle had one. So did Ulysses S. Grant. Abraham Lincoln grew one without a mustache, possibly to make a political statement.

Beards, whiskers, scruff, fuzz, stubble.

Facial hair has made appearances throughout history. And it pops up at various times on various faces for interesting reasons.

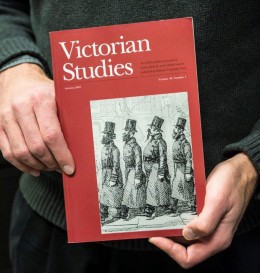

Christopher Oldstone-Moore, a history professor in Wright State’s College of Liberal Arts, has spent more than 10 years researching and chronicling the ebb and flow of facial hair – from Mesopotamia to the 2013 Boston Red Sox. His book “Brave Face: Beards, Shaving and the Cultural History of Manliness” will be published by the University of Chicago Press in January 2016.

Oldstone-Moore’s book on beards grew out of his teaching at Wright State and his desire to make his classes interesting, visual and include cultural history — literature, music and art. He began closely looking at busts and sculptures of figures in the Roman Empire and realized that all of the men were clean shaven.

“I decided to try to explain this, but when I looked I couldn’t find anything. There wasn’t any decent information,” he said. “I realized this is something that needed to be done.”

So Oldstone-Moore ran to his own area of specialty — Victorian England. He discovered that the popularity of beards exploded in 1848.

“Before 1848, facial hair was radical, politically charged,” he said. “If you wore facial hair, you were making a statement. And respectable men couldn’t make that statement.”

Oldstone-Moore started his research on facial hair by looking at his own area of specialty, Victorian England, and discovered that the popularity of beards exploded in 1848.

In 1848, a number of liberal and even radical revolutions broke out but failed. However, they opened the floodgates for beards because they eliminated the political stigma.

“You could wear them and not necessarily mean you wanted to overthrow the monarch,” he said. “So all of a sudden, boom — hair everywhere. I call it the beard movement.”

The movement was also fueled by changing social conditions in which women were seen as being increasingly in charge of the home and the maintenance of moral standards. Men felt that beards made them look more patriarchal.

“It was a transition thing where men are feeling like they were losing something, and so they were compensating for that sense of loss,” said Oldstone-Moore.

The beard movement also spread to America. Lincoln grew a beard because a little girl told him it would improve his appearance. And he had time away from the spotlight because presidential campaigning wasn’t considered proper.

“He wasn’t out and about, and people wouldn’t see him with his scruff,” said Oldstone-Moore. “He grew a particular kind of beard, one without a mustache. That was a style that was favored by the clergy and the Amish and the Mennonites.”

At the time, mustaches were associated with the military and considered aggressive. They had been favored by the Hungarian Hussars, cavalry troops whose military campaigns resembled today’s shock-and-awe attacks.

The soldiers would wear big fur hats and outfits that would make them look huge, wrap their saddles with leopard pelts, and wear silk sashes that would whip in the breeze when they charged. And they would grow big mustaches.

“The officers were actually required to grow a mustache,” said Oldstone-Moore. “And if they couldn’t, they had to put a fake one on. And it had to be black. So if they were blond, they had to dye it.”

Mustaches were later adopted for the cavalries of Napoleon, the British and most European armies.

“Because of that history, a lot of men who didn’t want to appear too military, who wanted to appear more peaceful, didn’t grow mustaches,” he said.

Christopher Oldstone-Moore served as a CELIA fellow in 2014, helping to organize Wright State’s World War I commemoration project “A Long, Long Way: Echoes of the Great War.”

Oldstone-Moore grew up in Platteville, Wis., where his politically active father was a professor at the university.

“Occasionally, some very famous people would come to our house,” Oldstone-Moore recalled. “I remember that Jon Voight was in our living room one time. He hung out for a couple of hours.”

The year was 1972. Voight — a rising star in Hollywood with major roles in “Midnight Cowboy” and “Deliverance” — was campaigning for presidential candidate George McGovern.

Oldstone-Moore became interested in history at a young age, influenced in part by his grandmother — who was born in 1895 and would tell stories about the beginning of the 20th century and World War I.

“My grandmother’s house in New Jersey was very well preserved from another era,” he said. “We had a World War I helmet in the attic that was my grandfather’s. The house just had a sense of time.”

The history bug also bit the boy when he went to the Chicago Museum of Science and Industry and saw “Yesterday’s Main Street,” an exhibit of businesses and storefronts as they would have appeared in 1910 Chicago.

And as a junior in high school, Oldstone-Moore spent eight months living in history-steeped Cambridge, England, when his father was a visiting scholar at Cambridge University.

“That’s magic when you’re that age,” he said.

Oldstone-Moore would go on to get his bachelor’s degree in history from Carleton College in Northfield, Minn., and his master’s and Ph.D. in British history from the University of Chicago.

He taught history at Carleton, the University of Chicago and Augustana College in Sioux Falls, S.D., before joining the faculty at Wright State in 2000.

Oldstone-Moore and his wife live in Springfield, where he sings with the Springfield Symphony Chorus and she teaches Asian religions at Wittenberg University.

Oldstone-Moore has taught history courses on the British Empire, South Africa and now one called Masculinity in Modern Europe. He teaches many of his courses like seminars.

“It’s more of a University of Chicago style, which is give the students something to see and ask them to wrestle with it, unpack it, synthesize, make something of it and work on that together,” he said.

Oldstone-Moore acknowledged that teaching history to the younger students can be challenging.

“What’s frustrating is getting them to realize why history matters at all. It doesn’t impress them,” he said. “They haven’t lived long enough to see it for themselves. All they need is five more years of adult life and they’ll get it.”

However, he said Wright State students have a great attitude.

“I’ve really had some of my best classes here at Wright State, and I’ve taught at several institutions,” he said. “The students here are hard working. They don’t take things for granted.”

Wright State is engaged in a $150 million fundraising campaign that promises to further elevate the school’s prominence by expanding scholarships, attracting more top-flight faculty and supporting construction of state-of-the-art facilities. Led by Academy Award-winning actor Tom Hanks and Amanda Wright Lane, great grandniece of university namesakes Wilbur and Orville Wright, the campaign has raised more than $125 million so far.

Centerville seventh grader wins Wright State University Regional Spelling Bee, advances to 2026 Scripps National Spelling Bee

Centerville seventh grader wins Wright State University Regional Spelling Bee, advances to 2026 Scripps National Spelling Bee  Three Wright State students win full year of tuition during Horizon League Championship game

Three Wright State students win full year of tuition during Horizon League Championship game  Walking through open doors

Walking through open doors  Adventures await

Adventures await  Wright State to expand nursing facilities to meet workforce needs and prepare more graduates for in-demand careers

Wright State to expand nursing facilities to meet workforce needs and prepare more graduates for in-demand careers