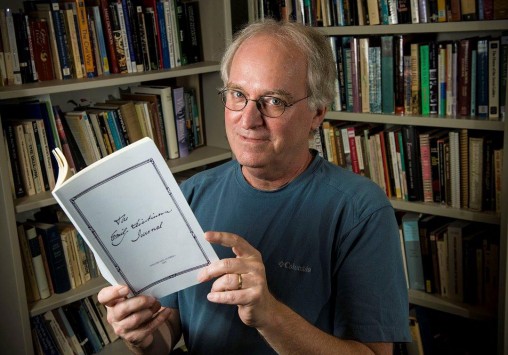

James Guthrie, an English professor at Wright State and internationally known Dickinson scholar, will assume the editorship of the Emily Dickinson Journal, the only publication devoted to the poet’s writing.

He’ll never forget it. It was during a graduate-school seminar on American poet Emily Dickinson. The professor had just read one of her poems and asked the class of 20 students what it meant.

“There was this dead silence in the classroom,” James Guthrie recalled. “I raised my hand and said, ‘It’s about this, this and that.’ And there was even more dead silence. These 19 students looked at me, and I thought, ‘Wow, something just happened here.’ Dickinson is a difficult poet for many people, but not for me. I hear her voice.”

Guthrie, Ph.D., an English professor at Wright State University and internationally known Dickinson scholar, is about to become even more deeply involved with the poet. He is assuming the editorship of the Emily Dickinson Journal, the only publication devoted to her writing.

The 24-year-old journal, which has long been printed at and distributed from Johns Hopkins University, will have a new home in the Department of English Language and Literatures in Wright State’s College of Liberal Arts. It will be the first national/international journal to be housed in the department.

“People submit articles to it internationally, so it will put the university’s name out there,” Guthrie said.

The most recent issue featured essays titled “Back Talk in New England: Dickinson and Revolution,” “Scarlet Experiments: Dickinson’s New English and the Critics” and “Disavowing Elegy: ‘That Pause of Space’ and Emily Dickinson’s Discourse of Mourning.”

Over the years, Guthrie has written books and scholarly articles on Dickinson and been a regular contributor to the journal. He was invited by the current editor, who is stepping down, to assume the editorship.

“I shook in my shoes for awhile, and the next day I said I’d do it,” he said. “I was kind of touched.”

Kristin Sobolik, dean of the College of Liberal Arts, has created a graduate assistantship, so Guthrie will get two English graduate assistants who will serve as assistant editors.

There will be four or five articles in the journal, which is published twice a year. The essays submitted for publication are reviewed by two volunteer readers, who don’t know the authors. Guthrie will have to maintain a stable of readers, who usually decide which articles will be published.

Guthrie sees his role as traffic cop and diplomat. He plans to retire from teaching next year, but continue as editor of the journal indefinitely.

Guthrie has just published “A Kiss from Thermopylae: Emily Dickinson and Law,” a book about Dickinson’s use of legal terms and concepts in her writings. He has also written about and is an expert on other American literary giants such as Walt Whitman, Herman Melville and Edgar Allan Poe.

A plastic Poe raven of “Nevermore” fame is clamped to Guthrie’s desk lamp, and he proudly displays a Poe action figure with a raven accessory that can be attached to Poe’s shoulder.

English and literature came natural to Guthrie, who as a boy would wade through mountains of history, art and travel books around the house. He especially liked poetry.

“My mother used to read it to me when I was young, so it never seemed strange to me or bizarre,” he said. “It was sort of normal.”

Guthrie’s father was a professor of economics and his mother a college reference librarian. Growing up, Guthrie moved from college town to college town — Ann Arbor, New Haven, Lexington and Champaign-Urbana.

He got his bachelor degree in creative writing at the University of Michigan. While he was there, he won the Hopwood Award for his poems and used the prize money to travel to Europe, where he hitchhiked and camped out.

“I did things then that would scare me to death now,” he recalled.

Guthrie landed a fellowship at the State University of New York at Buffalo, where he taught creative writing and obtained his Ph.D. in English. He got a job at North Central College in Naperville, Ill., teaching English and joined the faculty at Wright State in the early 1990s, where he teaches American literature classes, covering literature from arrival of the Mayflower to the Spanish-American War.

Guthrie said Dickinson is a big part of the American literary scene and is growing more popular. He attributes that to the women’s movement and the fact that women are taking a greater role in academia.

“They are intrigued at having an intellectual foremother,” he said. “And to some extent there is an interest in separating us from the British literary tradition. She’s a very American story.”

Dickinson grew up in the college town of Amherst, Mass., and was in the first generation of college-educated American women. Over her lifetime, she wrote 1,775 poems.

“There is a lot of stuff in her poetry about science, chemistry, astronomy,” Guthrie said. “She was a new type of American woman who was able to operate in these intellectual activities that only men had done.”

Guthrie said the fact that Dickinson became a recluse kept her from being influenced by other people.

“She was not made with the standard cookie cutter,” Guthrie said. “She was a very different kind of writer.”

Milling around

Milling around  Wright State recognizes Nursing Professor Kim Ringo for advancing international student success

Wright State recognizes Nursing Professor Kim Ringo for advancing international student success  Wright State honors graduating students for distinguished doctoral dissertations

Wright State honors graduating students for distinguished doctoral dissertations  Top 10 Newsroom videos of 2025

Top 10 Newsroom videos of 2025  Museum-quality replica of historic Hawthorn Hill donated to Wright State

Museum-quality replica of historic Hawthorn Hill donated to Wright State