Wright State is a founding partner of the Dayton Regional STEM School, which opened in 2009 and in June 2013 graduated its first class. Virtually the entire faculty and staff of the school are Wright State employees, and many of the teachers are Wright State graduates. (Photos by Erin Pence)

The welcome sign says “The Real World Starts Here.” On one wall hangs a Periodic Table of the Elements written in Chinese. And one student project involved learning the mathematics of origami that could be applied to a mission to Mars.

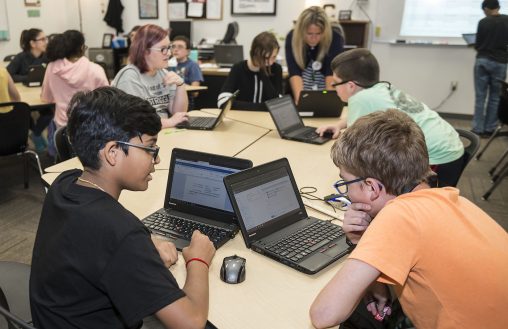

It’s all at the Dayton Regional STEM School, a Wright State University affiliate in Kettering that uses project-based learning to teach students in grades six through 12.

The public school, which is celebrating its 10th anniversary, was recently ranked by the Dayton Business Journal as the top performing high school in the Dayton area, topping schools in Springboro, Centerville, Oakwood and 36 others. The newspaper gave the STEM school an A-plus, noting its student/teacher ratio of 18:1 and its 85 and 83 percent proficiency in math and reading, respectively.

“The students who come here have great outcomes. And our project-based learning model is really exciting for them,’ said David Goldstein, chair of Wright State’s Department of Biological Sciences who serves as the president of the STEM school’s board. “Students respect each other and have a very strong sense of connectedness and constructive engagement.”

The state-funded school opened in 2009 and in June 2013 graduated its first class — talented seniors bound for the likes of Wright State, Emory, Purdue, Texas A&M, Ohio State, Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology and other colleges.

It is one of 44 public STEM (science, technology, engineering and math) designated schools across Ohio. They are designed to offer students a relevant, real-world education that prepares them for college and the working world. The students participate in inquiry and project-based instruction that marries traditional STEM content with social studies, language arts, the fine arts, and wellness and fitness. And the school serves as a training center to disseminate best practices across the region and state in the pedagogy of problem-based learning.

There are currently about 670 students — from 30 different school districts in six counties. There were 90 students in the first class, which was only ninth grade. The school later expanded to include grades six to 12. So far, there have been six graduating classes yielding more than 300 graduates.

About 30 percent of the school’s graduates attend Wright State, including several valedictorians. The majority go to college in Ohio.

“We view that as evidence of success because it helps build the 21st century talent pool for Ohio,” said Goldstein.

Four of every five students at the school plan to major in a STEM-related field in college. The national average is only one in four.

“And we infuse the STEM principles in the arts and the humanities,” said Stephanie Adams, the school’s community outreach director. “So whether they’re going into a STEM field or not, they’re still learning 21st century skills.”

About 30 percent of the school’s graduates attend Wright State, including several valedictorians. The majority go to college in Ohio.

Virtually the entire faculty and staff of the STEM school are Wright State employees. Many of the teachers are Wright State graduates. And the students all have Wright State email addresses.

Goldstein said most prospective students hear about the school by word of mouth and come because of its reputation for academic excellence, high graduation rate and high college attendance of graduates.

Because of the high number of applicants, fewer than half are accepted, which is done by the lottery system. Students who apply for admittance must commit to learning under the project-based model.

“Project-based learning really bases education in problems that are of interest to the students,” said Goldstein. “Everything is taught with a purpose and is not just abstract, so students connect with it really easily. I think the learning is deeper.”

Projects tackled by the students, who work largely in teams, have included everything from creating public service announcements about cancer to writing stories that were bound and distributed to hospitalized children.

One project involved students making origami structures that could be folded in a space-saving way. The real-world goal was to apply such ideas to a mission to Mars in which the students were challenged to design a room of the future where everything is foldable and easily transportable. The project featured a workshop with physicist Robert J. Lang, one of the foremost origami artists and theorists in the world.

Another project involved physics and arts teachers helping students design materials and then build them with 3D printers. A pencil-holder that resembles a DNA helix and sits on the desk of the school receptionist is testament to the project.

Starting in the sixth grade, students at the STEM school do computer coding for their own websites. And students are required to take at least two years of Mandarin Chinese.

For students who want to pursue their interests outside the classroom, there are an ocean of clubs to join, such as ones devoted to robotics, cybersecurity, community service and superheroes.

The Dayton Regional STEM School plans to add new classrooms, a place for school assemblies with a small stage, and the Gaming Research Integration for Learning Lab, a collaboration with the Air Force Research Laboratory.

Superintendent Robin Fisher said graduates leave the STEM school with some unique skill sets, such as their ability to communicate effectively.

“Our students do public speaking very often, and they’re taught how to do it well from the sixth grade on,” she said.

Fisher said teachers have a lot of autonomy and students have a voice and choice in what they do.

“I think it creates a lot of independent thinkers and problem-solvers,” she said. “They’ve got to work on a team. They’ve got to negotiate and compromise. They develop skills that companies and organizations want.”

The school continues to grow. An expansion project that begins Oct. 19 and is to be finished in March will take over two adjacent buildings and add 30,000 square feet to the facility.

The new space will include five classrooms, a place for school assemblies with a small stage, and the Gaming Research Integration for Learning Lab, a collaboration with the Air Force Research Laboratory that will focus on gaming software development for the Air Force and in school curriculum around the state.

One of the school’s hallmarks is how it partners with industry and community members to frame real-world problems and then to look for solutions.

“I think when students graduate they feel that their learning had a purpose,” said Goldstein. “A lot of them are on a path that’s connected to actual industry partners so they can see what their education is leading to.”

Walking through open doors

Walking through open doors  Adventures await

Adventures await  Wright State to expand nursing facilities to meet workforce needs and prepare more graduates for in-demand careers

Wright State to expand nursing facilities to meet workforce needs and prepare more graduates for in-demand careers  Wright State student-athletes make a lasting impact on local family with more to come

Wright State student-athletes make a lasting impact on local family with more to come  Wright State names Rajneesh Suri dean of Raj Soin College of Business

Wright State names Rajneesh Suri dean of Raj Soin College of Business