David Peterman, who is pursuing his Ph.D. in Environmental Sciences at Wright State, has discovered fossils from California to the Carolinas.

It was in middle-of-nowhere Montana in the summer of 2018. David Peterman had gotten there in a vehicle that bounced along dirt roads and even ran over a buried barbed-wire fence that flattened a tire.

The Wright State University graduate student was looking for important fossilized specimens of ammonites, externally shelled relatives of the squid that went extinct along with the dinosaurs nearly 66 million years ago.

Peterman cracked open a rock and there it was — an ammonite fossil that gave off a dazzling luminous glow. There was a shout of joy and amazement at the iridescence of the shell.

“When you pop it open it’s like opening a treasure chest,” he said. “You see lights and everything come out of it. It’s truly a fantastic feeling.”

That fantastic feeling has driven Peterman in pursuit of his Ph.D. in Environmental Sciences and in the past few years has led him and fellow grad student Ryan Shell on scores of Indiana Jones-like field expeditions around the country.

“I’ve been everywhere,” said Peterman. “It’s an actual adventure because you never know what you’re going to find.”

Peterman and Shell chronicled some of their adventures and findings in a story published in the latest issue of The Professional Geologist. The publication is produced by the American Institute of Professional Geologists, the largest association dedicated to promoting geology as a profession, with more than 6,000 members around the world.

Peterman has also published some of his dissertation research in several different paleontology journals, including Lethaia, Palaeontologia Electronica, Acta Palaeontologica Polonica and Paleobiology.

“My work isn’t complete until it’s disseminated to others,” said Peterman. “If I just sit on it, I might as well have never done the research at all.”

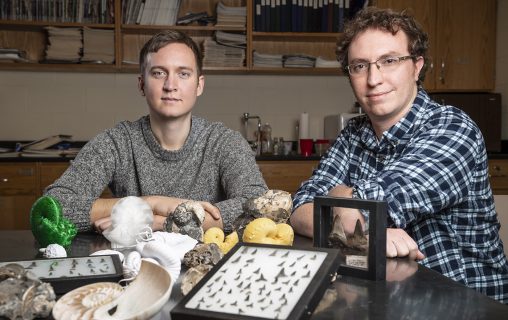

Earth and environmental sciences Ph.D. students David Peterman, left, and Ryan Shell chronicled their adventures hunting for fossils in The Professional Geologist.

Peterman studies the quantitative paleobiology of ectocochleate cephalopods, focusing on virtual reconstruction and biomechanics. He builds 3D models of the fossils from using photos, CT scans and equations.

“From the equations, I can study the physics that would have acted on them while they were alive — their mass, their buoyancy, their stability, their orientation,” said Peterman. “That is all really important because those pieces of information help us know how they interacted with their surroundings, with each other, and whether they were predators, swimmers or passive drifters.”

His work on specimens of the ammonite Baculites from South Dakota led to a fundamental shift in the historical understanding of how it and all other straight-shelled cephalopods swam through ancient seas.

“Understanding what’s going on with ammonoids has potential for understanding organisms that make up a tremendous amount of Earth’s history,” he said. “All of these physical properties I’m computing have been based on limited evidence until now. So it’s really important that we have this real data to truly understand what these animals were doing.”

Peterman grew up in Pataskala, east of Columbus. He developed a passion for collecting rocks and shells when he was about 5 years old. His parents would sometimes take him to Caesar Creek State Park to hunt for fossils.

After graduating from Watkins Memorial High School in 2010, Peterman attended Ohio State University’s Newark campus and then transferred to Wright State.

He earned his bachelor’s degree in earth and environmental sciences and his master’s in geophysics before beginning the study of paleobiology in pursuit of his Ph.D. His dissertation is on the three most common shapes of ammonoids in the U.S. western interior and the physics that acted on them while they were living.

“I love the geology classes,” he said. “The professors really got me interested in geophysics and helped improve my quantitative outlook of the field.”

After graduation, Peterman wants to remain in academia and do research in a new field that is a microcosm of paleontology.

“I could study this for the rest of my life because there is so much unfinished work,” he said.

Peterman has done fieldwork all over the country, including at sites in Montana, the Dakotas, Texas, Tennessee, Mississippi and the Carolinas.

Peterman studies the quantitative paleobiology of ectocochleate cephalopods, focusing on virtual reconstruction and biomechanics.

Collecting fossils can be physically exhausting. It sometimes requires lugging rocks weighing 50 pounds and more up and down hills and in the rain.

“It’s very, very tough,” said Peterman. “We bust the rocks open to see what’s inside, put them back together, shrink-wrap them and carry them as long as we need to.”

Last year, Peterman and Shell presented their research findings at the Geological Society of America meeting in Phoenix. They have also presented at conferences in San Francisco, New Orleans, Indianapolis and Washington D.C., among other places.

This spring, Peterman and Shell taught a field course called Atlantic Coast Paleoecology, which took place at fossil sites from coastal Virginia to South Carolina. Students collected fossilized mollusks as old as 70 million years and witnessed the effects of changing temperature, sea level fluctuation, and oceanic circulation changes on the evolution of prominent marine species of the Atlantic coast.

Peterman and Shell say their fieldwork and associated travel has given them the skills to better understand the complexity of the world.

“It also led to a major shift in the way we think about geology as teachers, changing the way we teach in the classroom and enabling us to teach outside of the classroom as well,” the two wrote in The Professional Geologist. “We hope to use what we have learned in the classroom and field as Ph.D. paleontologists to educate and inspire our students and readers for the rest of our careers.”

Walking through open doors

Walking through open doors  Adventures await

Adventures await  Wright State to expand nursing facilities to meet workforce needs and prepare more graduates for in-demand careers

Wright State to expand nursing facilities to meet workforce needs and prepare more graduates for in-demand careers  Wright State student-athletes make a lasting impact on local family with more to come

Wright State student-athletes make a lasting impact on local family with more to come  Wright State names Rajneesh Suri dean of Raj Soin College of Business

Wright State names Rajneesh Suri dean of Raj Soin College of Business