Ryan Shell, an earth and environmental sciences Ph.D. student, studies the biodiversity, biogeography and paleoecology of marine vertebrates during the early Permian Period specializing in sharks.

A search for the fossilized remains of prehistoric sharks has taken Ryan Shell through dozens of states, from the Mojave Desert in California to the Carolina coast. The Wright State University graduate student has recovered the teeth of the hook-toothed mako shark, a long-necked plesiosaur and even part of a prehistoric baleen whale.

A Ph.D. candidate, Shell studies the biodiversity, biogeography and paleoecology of marine vertebrates during the early Permian Period, specializing in sharks.

“Sharks are incredibly persistent vertebrates throughout the fossil record,” said Shell. “Because of that, we have this long evolutionary history of these animals in response to changes in climate, ocean circulation, and other ecological shifts.”

Shell and fellow grad student David Peterman chronicled some of their adventures and findings in a story published in the latest issue of The Professional Geologist. The publication is produced by the American Institute of Professional Geologists, which is dedicated to promoting geology as a profession, with more than 6,000 members around the world.

“It was a real honor to be asked,” said Shell. “It’s cool that Dave and I can tell paleontological stories in a publication that is read mostly by professional consulting geologists, geochemists and water-quality researchers.”

Last year, Shell and Peterman presented their research findings at the Geological Society of America meeting in Phoenix. They have also presented at conferences in San Francisco, New Orleans, Indianapolis and Washington D.C., among other places.

Shell grew up in Benton, Arkansas. As a young boy, he was obsessed with dinosaurs, which led to an interest in other ancient organisms. After graduating from Benton High School in 2009, Shell enrolled at the University of Arkansas, where he earned a bachelor’s degree in geology.

“I knew geology would be a good place to start for an understanding of paleontology,” he said.

Shell began finding vertebrate fossil sites in northwest and northern Arkansas that were really interesting to him.

“They contained very, very rare animals we had few examples of,” he said. “The fossils were primarily sharks and shark-like animals.”

That got Shell working with Chuck Ciampaglio, professor of earth and environmental sciences at Wright State’s Lake Campus. Ciampaglio is one of the world’s leading authorities on prehistoric sharks.

As one of Ciampaglio’s graduate students, Shell began pursuing his master’s degree and then went into the Ph.D. program, where he studies vertebrate paleontology, specifically the ecology of very early sharks under Ciampaglio’s tutelage.

Shell’s dissertation is based on fieldwork at five fossil sites from central Texas to Kansas spanning the early Permian Period. The community Shell glimpsed in a quarry in Texas turned out to be one of the most biodiverse fossil sites for early Permian marine vertebrates on the planet and led him to investigate three more fossil sites, each of them rivaling the species richness of sites explored before.

In the past five years, Shell has done fieldwork in 35 states.

“A big part of fieldwork is just getting to the remote sites. The digging itself can be physically demanding, depending on the density of the sediment,” said Shell.

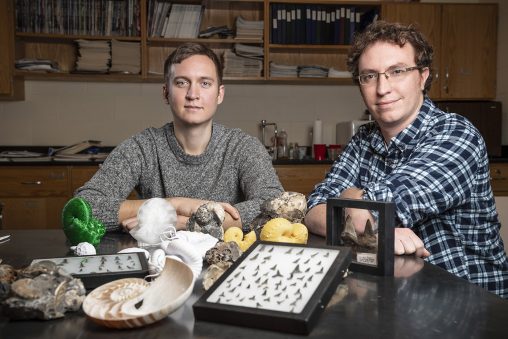

Earth and environmental sciences Ph.D. students David Peterman, left, and Ryan Shell chronicled their adventures hunting for fossils in The Professional Geologist.

Snowstorms and flash floods have made it even more difficult in the past.

“One of the things I really appreciate is that geology and paleontology is that both are very hands-on sciences,” he said. “Being able to apply the knowledge you learn in the classroom directly is thrilling, but there is also the simple interest in discovery. Anything we find will see the light of day for the first time ever.”

Shell said Ciampaglio has been a great teacher and mentor and helped Shell be prepared when he does fieldwork. He said the Wright State program also stresses independence of thought and action.

Shell says paleontology is useful for a broad range of topics because it is a field that requires an understanding of chemistry, calculus, physics and biology. Paleontologists often work as museum curators.

“Fossils serve no one in the ground,” said Shell. “Keeping those fossils, keeping them safe, preparing them, cleaning them up and extracting information from fossils that have been excavated is really crucial.”

Paleontologists also have careers in education.

“Being able to communicate information about fossils in the classroom and in interviews and articles is really important,” he said. “Like astronomy, paleontology benefits hugely from educating the public on the lowest levels as well as the high.”

This spring, Shell and Peterman taught a field course called Atlantic Coast Paleoecology, which took place at fossil sites from coastal Virginia to South Carolina. Students collected fossilized mollusks as old as 70 million years and to understand the effects of changes in temperature, sea level and oceanic circulation on those fossils.

Shell and Peterman say their fieldwork and associated travel has given them the skills to better understand the complexity of the world.

“It also led to a major shift in the way we think about geology as teachers, changing the way we teach in the classroom and enabling us to teach outside of the classroom as well,” they wrote in The Professional Geologist. “We hope to use what we have learned in the classroom and field as Ph.D. paleontologists to educate and inspire our students and readers for the rest of our careers.”

Walking through open doors

Walking through open doors  Adventures await

Adventures await  Wright State to expand nursing facilities to meet workforce needs and prepare more graduates for in-demand careers

Wright State to expand nursing facilities to meet workforce needs and prepare more graduates for in-demand careers  Wright State student-athletes make a lasting impact on local family with more to come

Wright State student-athletes make a lasting impact on local family with more to come  Wright State names Rajneesh Suri dean of Raj Soin College of Business

Wright State names Rajneesh Suri dean of Raj Soin College of Business