Note to students of David H. Wilson, professor of English at the Wright State University Lake Campus – listen up.

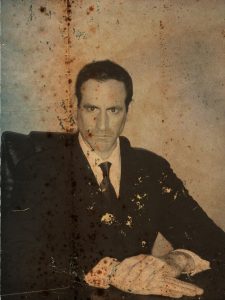

Wilson has taught 15 different courses at the Lake Campus, is the author of more than 30 books of fiction and nonfiction, and released a new science fiction novel, “Outré,” which has drawn sit-up-and-take-notice reviews.

“I learned to write by reading, reading, reading … and reading some more,” said Wilson, who is also director of humanities and social sciences at the Lake Campus. “I studied how different writers rendered prose in tandem with content. Then I put into practice what I studied, emulating other writers at first and eventually finding my own voice.”

James Joyce and Thomas Pynchon come to mind when reading Wilson’s mind-bending prose. The unpredictable vectors of his writing jolt the reader. It’s not a gentle ride. But it’s transformative.

“In addition to genuine innovation, my primary objective as a writer is to displace readers from their comfort zones and force them to get involved in the creative process with me,” said Wilson, who writes under the pseudonym D. Harlan Wilson. “All of my book-length fictions do this to varying degrees in the tradition of literary modernism.”

Wilson began writing “Outré” about 10 years ago, putting it aside for other projects from time to time until 2017, when he forced himself to complete a full draft.

“As with much of my fiction, it’s heavily influenced by the media environment and celebrity culture, which I love to probe, parody and critique,” he said.

Here’s the publisher’s description of the 121-page book: “In a future where cinema has usurped reality and there’s nothing special about effects, an aging movie star takes on the role of a lifetime, growing the flesh of an otherworldly kaiju onto his body. At the same time, all of the roles he has played in the past fight for control of his psyche and identity as agents of the media prey upon him. The result is alcoholism, ultraviolence, psychosis … and the promise of eternal life.”

Wilson earned his bachelor’s degree in English from Wittenberg University, a master’s degree in English from the University of Massachusetts-Boston in 1997, a master’s degree in science fiction studies from the University of Liverpool in 1998 and a Ph.D. in English from Michigan State University in 2005.

After graduating from Wittenberg, Wilson worked for his father’s international company for two years, traveling all over the world. But he was more interested in art and literature than business and began writing fiction during his first year at UMass-Boston.

In Boston, Wilson worked as a bouncer at a nightclub and did odd jobs for Harvard University’s Widener Library to make extra cash. He has also worked as a model and actor, taught as an adjunct faculty member at various colleges and was a visiting professor at Michigan State. He joined the faculty at Wright State in 2006.

“I can’t say enough good things about the Lake Campus,” said Wilson. “Students appreciate the small classroom settings and the close access to their instructors. The landscape is beautiful, and there remains great possibilities for expansion, growth and further prosperity. It’s exciting to think of what the future might bring us.”

Among the courses Wilson has taught at the Lake Campus are Academic Writing and Reading, Research Writing and Argument, Great Books, African American Literature, Business Writing, Introduction to Fiction Writing, Studies in American Literature, Studies in Literary Theory, and Technical Communications for Engineers and Computer Scientists.

In addition to being the author of more than 30 books of fiction and nonfiction, Wilson has published hundreds of stories, essays and reviews in journals, magazines and anthologies around the world in multiple languages. He is also editor-in-chief of Anti-Oedipus Press and the reviews editor of the academic journal Extrapolation.

“I have a big imagination, but I am by no means innately ‘talented,’” said Wilson. “I have a good work ethic. That matters more than anything.”

Wilson writes slowly, usually no more than a few paragraphs a day. But he writes every day and works on multiple writing projects at the same time.

“Typically, I write for an hour or so every morning, then return to it for 10 or 15 minutes at a time when I have a break,” he said. “I don’t write at night: my brain hits a wall. Nighttime is for reading.”

Some of Wilson’s written work stems from his experience as a professor, his interest in media studies and his affection for surreal cyberpunk.

“The human condition is chaotic, rhizomatic, eruptive and disruptive,” he said. “The process of thought in particular is a mess. I like to think that my fiction represents this mess in highly organized, stylized, dramatic and humorous ways.”

Wilson’s first novel, “Dr. Identity,” is a satire of academia, a science fiction novel set in an absurdist, dystopian future where everybody who can afford them has surrogate robots called gängers to perform their daily tasks. It won the first Wonderland Book Award for best novel in 2007.

Each chapter of “Outré,” which has more than 100 characters, is essentially a short paragraph. The protagonist, Curd, is a movie star, and it’s set in a “post-real” world where death has become extinct.

“Outré” was released on Nov. 15 by Raw Dog Screaming Press, which describes itself as a publisher of “fiction that foams at the mouth.”

Says Library Journal about “Outré”: “Wilson’s latest is a wild, surreal modern trip down the rabbit hole. Anyone who enjoys stream-of-consciousness stories, as well as fans of artists Salvador Dalí and René Magritte, will enjoy this hallucinatory dreamscape.”

“Heatedly gonzo. His range of stories is very broad,” said The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Publishers Weekly has said of Wilson’s writing: “Wilson invokes not a dialogue with the reader but a bare-knuckle fistfight. Dizzying, disorienting, smooth and shocking.”

One of this reader’s favorite chapters in “Outré” is titled “Ago”: “The weight of the future; the teeth marks of the past – I can’t decide which one causes more harm. Memory traumatizes us more than foresight, or so it seems: both afflictions stem from the same areas of activity in the brain. ‘I never lie,’ I inform the herd. ‘My memory is the one that lies. I simply open and read the letters that my mnemonic postman delivers to me. It’s not my fault if the letters are misleading. Memory is fallacious by default. That’s why history is a fairytale. The best we can do is make educated guesses about what happened in that pileup of yesterdays. It’s in everybody’s best interests to revise the past as it unfolds from the present like tape from a stock ticker.”

Adventures await

Adventures await  Wright State to expand nursing facilities to meet workforce needs and prepare more graduates for in-demand careers

Wright State to expand nursing facilities to meet workforce needs and prepare more graduates for in-demand careers  Wright State student-athletes make a lasting impact on local family with more to come

Wright State student-athletes make a lasting impact on local family with more to come  Wright State names Rajneesh Suri dean of Raj Soin College of Business

Wright State names Rajneesh Suri dean of Raj Soin College of Business  ‘Only in New York,’ born at Wright State

‘Only in New York,’ born at Wright State