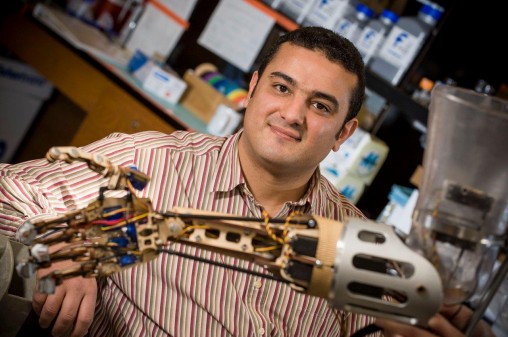

Wright State neuroengineer Sherif Elbasiouny received a three-year, $433,000 grant from the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency to try to make upper limb prostheses feel and function like natural limbs.

It’s an exciting idea — enabling amputees to actually feel baseballs, eggs, coffee cups and other objects they grasp with artificial arms. And that’s exactly what Wright State neuroengineer and assistant professor Sherif M. Elbasiouny, Ph.D., has set his sights on.

Elbasiouny has a three-year, $433,000 research grant from the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) to try to make upper limb prostheses feel and function like natural limbs.

And the grant comes at a time when Elbasiouny and his fellow researchers are preparing to occupy Wright State’s new Neuroscience Engineering Collaboration (NEC) Building, which will put neuroscientists, engineers and clinicians under the same roof. The $37 million, four-story building is scheduled to open in mid-April.

“The impact is going to be huge on the research,” Elbasiouny said. “The space we’re receiving will allow us to do more work. It’s an exciting time to be at Wright State.”

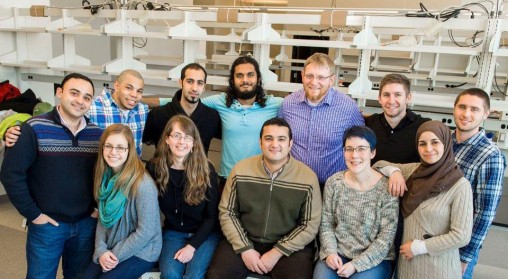

Elbasiouny and his self-described Neuro Engineering Rehabilitation Degeneration (NERD) team are digging in to their prosthesis work.

Their intent is to infer an amputee’s motor intent from the activity of residual nerves (nerves cut after amputation) and translate that to a signal that moves the artificial limb in a natural way — as fast and in the exact direction the amputee wants.

Prosthesis hardware is equipped with sensors, including pressure sensors that give off signals when amputees close their hands on objects. Elbasiouny and his team will develop algorithms designed to encode the sensor signals in a way that communicate with the nervous system.

“Hopefully, that will evoke natural sensation, giving the amputee the feeling of touch,” he said. “This is a more natural way of control.”

In addition to his work on artificial limbs, Elbasiouny has a five-year, $1.6 million grant from the National Institutes of Health for research on amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), or Lou Gehrig’s disease. The disorder involves the death of neurons and is characterized by progressive muscle weakness that leads to paralysis, difficulty speaking and swallowing and eventually death due to respiratory failure.

“Our mission as a lab is to help people with disabilities have a better life,” he said. “This is why we do the work we do.”

Sherif Elbasiouny and his Neuro Engineering Rehabilitation Degeneration (NERD) team will be among the neuroscientists, engineers and clinicians working in the new Neuroscience Engineering Collaboration Building when it opens in April.

That laser-like determination showed itself when Elbasiouny was an undergraduate student at Egypt’s Cairo University.

He had enrolled in a class called rehabilitation engineering in his senior year, but was the only student in the class. The department chair was preparing to cancel it, but Elbasiouny saved the one-person class with an impassioned plea.

“I wanted to have an impact on the lives of people,” he said. “I was chasing medicine, but knew I wanted to be an engineer.”

Elbasiouny grew up in Cairo. His father was a pilot for EgyptAir and would take the family on his trips that would result in them staying for weeks at a time in Bangkok and Tokyo.

“When I was young, I wanted to be a pilot like my dad,” Elbasiouny said. “But my dad was not happy about that. He realized that the profession is unstable, very stressful on the family.”

Elbasiouny later became interested in medicine, but not in being a physician. He was fascinated at how engineers think — how they solve a problem by breaking it down into parts and creating a solution.

After getting his bachelor’s and master’s degrees from Cairo University, Elbasiouny began work on his Ph.D. in neuroscience at the University of Alberta in Edmonton, Canada, in 2002. It was there that he used computational neuroscience to help people who had suffered spinal cord injuries.

The injury interrupts the signal from the brain to the spinal cord. Micro wires can be implanted into the spinal cord below the injury to deliver electrical signals that activate the cells directly and help the patient move. But the cells can’t be controlled by the brain anymore, which can result in spastic motions by the patient.

“My goal was to design electrical stimulation signals that we could deliver through the implanted micro wires in the spinal cord and control the behavior of the cells,” Elbasiouny said. “If patients had a spastic episode, they could use the stimulation to relax their spastic limb.”

In 2008, Elbasiouny began post-doctorate work at Northwestern University, where he combined experiments with computational neuroscience to study ALS. His post-doctorate work was funded by the ALS Society of Canada and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

He joined the faculty at Wright State in 2012, attracted by the university’s strong neuroscience program and expert faculty that included the likes of Robert Fyffe, vice president for research and dean of the Graduate School, and Timothy Cope, chair of the Department of Neuroscience, Cell Biology and Physiology.

“I didn’t hesitate,” Elbasiouny said.

The opportunity to have his own lab and to work in the new NEC Building was also irresistible to Elbasiouny, who has joint appointments in the College of Engineering and Computer Science, the College of Science and Mathematics and the Boonshoft School of Medicine.

“Our lab being one of neuroscience and engineering is exactly the multidisciplinary nature of what the NEC Building is all about,” he said. “Neuroengineering is booming here. This really feels like home.”

Walking through open doors

Walking through open doors  Adventures await

Adventures await  Wright State to expand nursing facilities to meet workforce needs and prepare more graduates for in-demand careers

Wright State to expand nursing facilities to meet workforce needs and prepare more graduates for in-demand careers  Wright State student-athletes make a lasting impact on local family with more to come

Wright State student-athletes make a lasting impact on local family with more to come  Wright State names Rajneesh Suri dean of Raj Soin College of Business

Wright State names Rajneesh Suri dean of Raj Soin College of Business